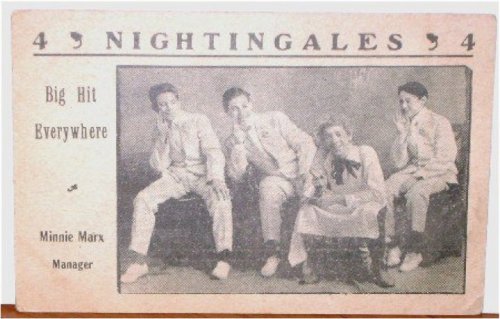

As Minnie “Palmer” Marx began expanding her vaudeville production empire, Leo took more direct control of the Brothers’ act.

In 1911, a new fad was reinventing the face of vaudeville — the tabloid musical, or “tab” as they were quickly dubbed by the trade papers. In the words of Robert S. Bader, tabs were “truncated versions of popular Broadway and touring shows, reduced by cutting much of the dialogue, removing non essential characters, and leaving the musical numbers and just enough of the plot to maintain some semblance of the original idea of the show.” The more respectable vaudeville houses began clamoring for shows consisting of a couple of classy tabs, rather than a low-rent, crazy-quilt collection of short, unrelated acts. And fewer acts on a bill meant fewer salaries had to be paid and more profit for the theaters. When the craze got too popular, Broadway producers began cracking down on copyright violations. Even with vaudeville companies legitimately paying for the material, demand outweighed supply. This led to the creation of more tabs featuring original material.

And that’s what put the light bulb on in Leo’s head when he and his erstwhile performing partner George Lee joined forces with the Three Marx Brothers in the late summer of 1912. Leo decided that the school act could be polished, tweaked, and refined into a tabloid musical. They could then hire a few supporting acts, and sell the whole thing as a self-owned, self-contained package.

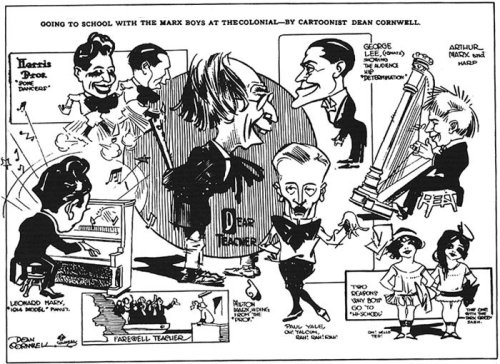

In its new form, the two parts of Fun in Hi Skule (the classroom and the recital) would be condensed into the first act. A newly-minted second act (created with a little help from Uncle Al) would be more comedy and music in the form of a ten-year-class reunion in honor of the retirement of Julius’ teacher character, now named Mr. Herman Green. Arthur kept his Patsy Brannigan character. The dim-witted class disrupter of the first act had grown into the local garbage man by the second. (“Patsy Brannigan the garbage man is here.” “Tell him we don’t want any.” When and where this big laugh-getting line was first used is yet another element of the early days that is awash in contradictory stories.) He also continued to refine his costume, which was growing less Irish stooge and more tramp-like clown. But despite “Patsy” no longer being explicitly Irish, ethnic stereotypes were still firmly entrenched in the world of vaudeville. Leo became the Italian student, Tony Saroni. George Lee, with his bigger performance style and firmer command of Yiddishisms, took over the role of the Jewish student, now named Ignatz Levy. Milton dug the name “Hans Pumpernickel” out of retirement, and became the German student in a pageboy/”Hansel”-style wig. Paul Yale remained as his “nance” character, but toned down the more overt homosexual mannerisms and became more of a prissy “mama’s boy” (the audience would gasp, then crack up when Yale, in his knee pants and heavily-rouged cheeks, opened his mouth and sang in a deep, manly baritone.) The main support act was the dancing Harris Brothers. And the “schoolgirl” chorus had expanded to fifteen young women, still including the trouper Dot Davidson, who had been with them since the end of 1910, possibly due to her passionate attachment to Yale.

The schoolroom act still comprised the first half of the revised show. Julius is at the center, apparently delivering a harsh lecture to Dot Davidson, while the schoolgirl chorus on the left points and laughs. Arthur, on the right, is also getting in on shaming Davidson. New cast member Leo is in the background, bullying the Harris Brothers. In front of them is “sissy” Paul Yale and Milton as the updated version of “Hans Pumpernickel”

The whole shebang was titled Mr. Green’s Reception, and it was the first time the Four Marx Brothers shared a stage. It ran a full forty minutes, and the Marx Brothers touring company now included a stage carpenter and property manager in addition to its cast, supporting acts, and chorus line. The cast appeared in white-tie evening dress for the second act. As was the case with most mid-level vaudeville acts, they did not tour with musicians (apart from those in already in the cast), but carried sheet music for all of their numbers, arranged for anything from a four-piece to a full dance orchestra, depending on the size of the theater and its resident house band.

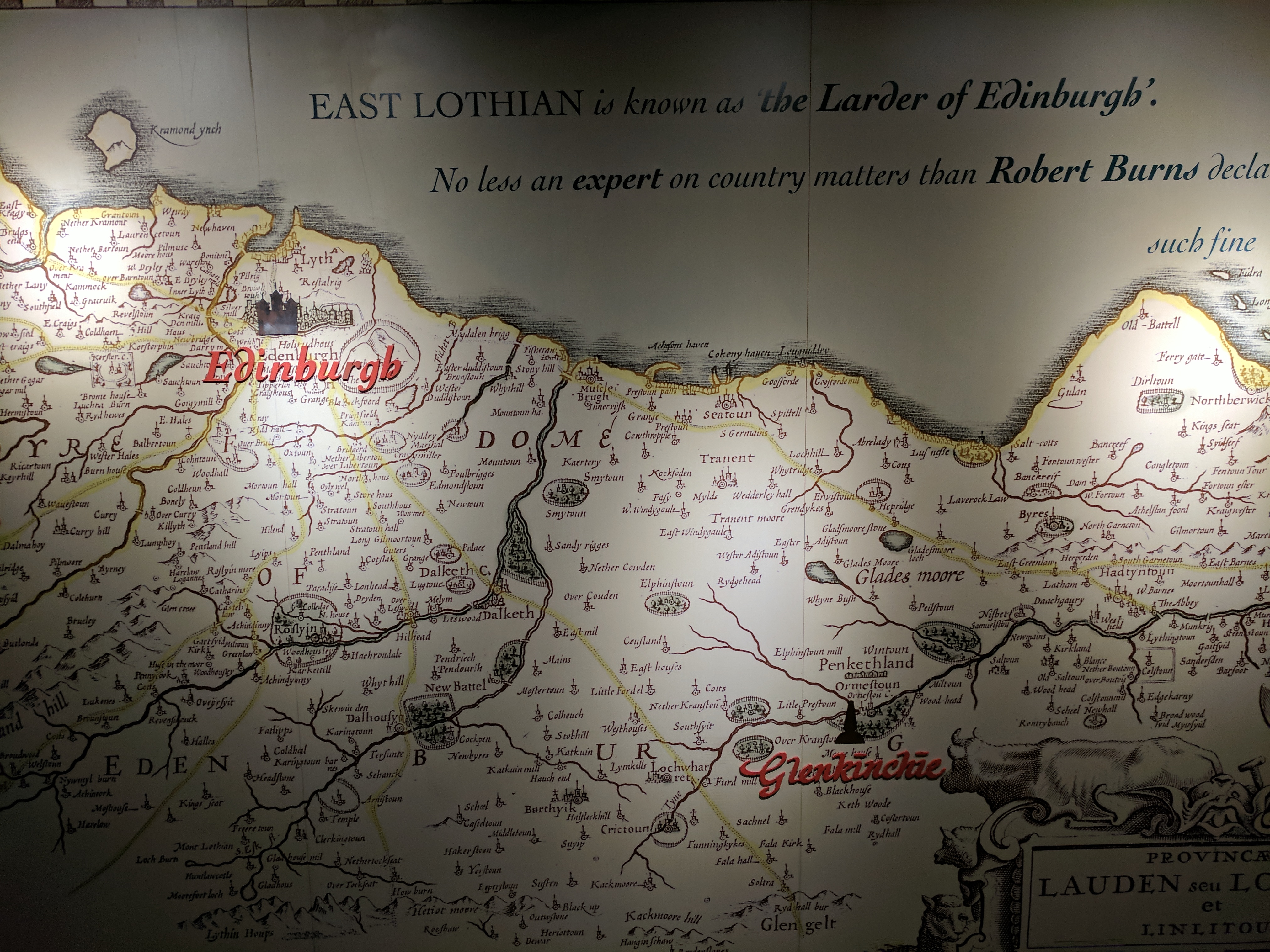

Mr. Green’s Reception started its run in Chicago on September 5, 1912, and was eagerly booked by the WVMA circuit for the entire 1912-1913 vaudeville season. The big-time beckoned, tantalizingly near. But they had yet to attain name recognition. They weren’t stars quite yet. They would come to town, get the audiences roaring (Leo’s piano-playing, Arthur’s ever-improving harp solos…and the Harris Brothers’ clogging…were all considered highlights), earn decent reviews in the local paper, and then were forgotten about as soon as the act left town. Not for much longer.

From the Burlington, Iowa Hawkeye, Dec. 20, 1912: “Judge W.S. Winthrow cut short his luncheon period yesterday to unite in marriage Mr. S. Paul [Yale] and Miss Margaret [Dot] Davidson, two young people who are playing at the Garrick Theatre this week. The thespians secured a marriage license at 11 o’clock and asked if they might see the judge…”

Time was of the essence, as Dot was six weeks pregnant. It was at that same Garrick Theater where the Brothers had several run-ins with a particularly nasty theater manager. (The story goes he paid the company’s salary in pennies. Hate to burst the anecdote bubble yet again, but this would have been pretty much impossible. Remember the size of the Marx Brothers’ company? And have you seen a few thousand dollars in pennies?) As their train pulled out of town, according to Marxian legend, Arthur stood on the back platform of the last car, shook his fist at the receding town, and yelled “You lousy sonofabitch, I hope your goddamn theater burns to the ground!” “The next day, it did,” Julius always loved to recall. “And that’s why we decided not to let Harpo talk.” (As with any legend, there’s a kernel of truth — Arthur may very well have cursed the theater as he left town, and the Garrick Theatre really did burn down, but not until two months later. And Arthur continued speaking onstage for at least another year-and-a-half.)

By the time the Garrick had been reduced to ashes in February of 1913, Mr. Green’s Reception was playing in South Bend, Indiana. South Bend was experiencing record low temperatures, and the St. Joseph River was choked with ice.

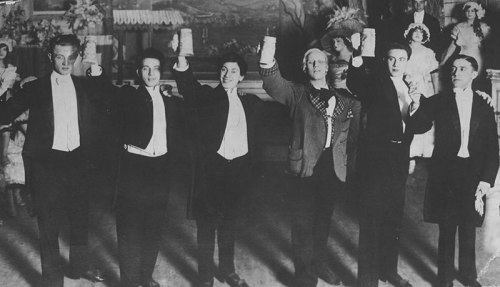

The Mr. Green’s Reception company, in costume — Julius as Mr. Green is in the back row with the girls. Milton, Leo, and Arthur are front and center. Paul Yale is on the far right, his arm around a Harris Brother, with George Lee on the far left. Looks like the other Harris Brother volunteered to take the picture

A scrapbook clipping from the local South Bend paper (name & date unknown): “Mr. [Arthur] Marx was on the bank of the stream in the rear of the Orpheum Theatre with others of the Orpheum troupe when one of the women…bet him 50 cents that he was afraid to take a swim. ‘I’ll bet you another 50 cents.’ ‘And I another,’ answered two others. Before taking the plunge, Mr. Marx said: ‘That’s a dollar and a half when I get out, ain’t it?’ He then dove from the ledge of ice, clothes, hat, and all. He came to the surface with chattering teeth, exclaiming, ‘It’s not so bad.’”

Jumping into icy rivers was only one way to pass the time. Stories of the Brothers’ affairs with the chorus girls that came and went from their show, and their necessarily brief dalliances with local women, fill their biographies and autobiographies and are at this point impossible to verify, but it seems sex on the road was very much part of their routine. Sometimes, when it came to the local whorehouses, it was almost too easy. “The girls used to come watch us at the theater,” said Julius. “And if they liked us, they’d send a note backstage inviting us over after the show.” Presumably, the services were discounted or maybe even gratis.

Raising a stein at the curtain call for Mr. Green’s Reception — l. to r. Paul Yale, Leo, Arthur, Julius, Milton, George Lee

The company also had the novel idea of forming a baseball team, and when not performing, rehearsing the house orchestra, or pursuing women, took on local college teams — and usually lost big. (For the curious: Catcher — Julius. First base — Paul Yale. Second base — George Harris. Shortstop — Arthur. Third base — Leo. Left field — Milton. Center field — stage carpenter Fred Browning. Right field — George Lee. Pitcher — Victor Harris.) The uniforms proudly had “MARX BROS.” printed across the chest.

Mr. Green’s Reception toured another full year, and exhaustion was beginning to set in by the spring of 1914. The grind of the road and the close quarters caused tempers to grow short. George Lee, whom many reviewers had indicated was the “principal comedian” of the act, and also their best singer, had already found another job as a solo act for the following season, and would be leaving the Marx Brothers company at the end of the tour. With only a couple of months left to go, Lee demanded a raise. Not seeing the sense of giving more money to someone who was just going to be taking off soon, the Brothers refused. “As the size of his head grew, he decided his salary should grow with it,” said Julius. Lee abruptly quit in early April of 1914. Paul Yale and Dot Davidson took the opportunity to leave the act at the same time. They formed their own song-and-dance duo, Yale & Davidson, and occasionally worked as a supporting act for the Brothers through 1916.

Mr. Green’s Reception company out of costume. Milton is top center, with Paul Yale to the right. Just below them is Julius. Arthur and George Lee kneel in the foreground. Leo is off to the left

The Brothers hired some replacements, and the company finished out the season, but the situation left Julius with a realization:

“For the first time in our career we realized we could succeed as an act without any outside help. We didn’t need any more extraneous singers, dancers, and feeble comedians. We were now a unit. We were the Marx Brothers…we had finally freed ourselves from always having some outsider along to put us over, and from then on we were able to steam on under our own power.”

And it was during those closing days of the final Mr. Green’s Reception tour that Something Momentous happened…

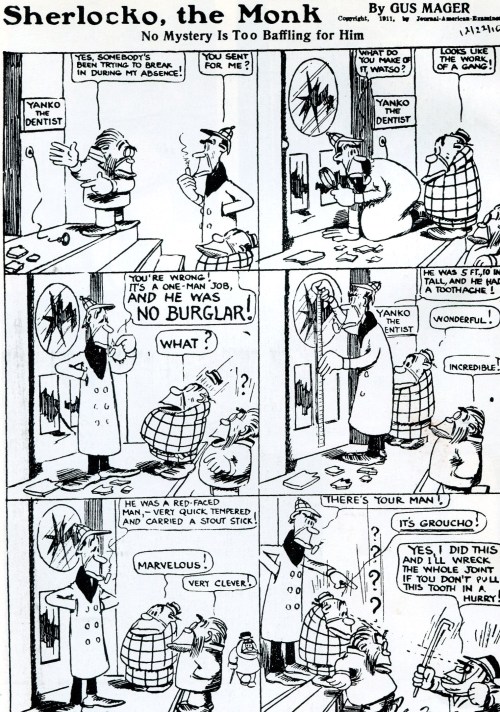

It was the very beginning of the Platinum Age of Comics. When the newspaper hit the front step, many adult readers would flip right to the “funny pages,” skipping the depressing headlines to enjoy the adventures of the Katzenjammer Kids, Maggie and Jiggs, Mutt and Jeff, and Krazy Kat. In 1904, artist Gus Mager created a series of comic strip characters called “monks,” after their vaguely monkey-like faces. All the monks had names ending in “o.” For a brief period, these characters featured in a strip called Sherlocko the Monk, in which the title character solved mysteries. Sherlock Holmes creator Sir Arthur Conan-Doyle threatened a lawsuit, and in 1913 the title of the strip was changed to Hawkshaw the Detective (and the characters redesigned to look a little more human). But the impact of “Sherlocko” and his fellow monks remained. Vaudeville and popular culture in general went through a fad of nicknames ending in “o.”

This is said to be the only picture in existence of all five brothers and their parents together. Outside the theater in Joilet, Illinois, April 30, 1914

The Brothers always agreed it happened in Galesburg, Illinois, which would make it mid-May of 1914. They were sharing a bill with a someone named Art Fisher. Over a round of backstage poker between shows, Fisher and the Brothers were idly discussing the “o” nickname phenomenon. As Fisher dealt the cards, he assigned each Brother an “o” name. “He named me Gummo,” said Milton, “because I had holes in my shoes and I’d wear rubbers, or gumshoes, over them even when it wasn’t raining.”

Arthur became “Harpo” for obvious reasons.

Leo became “Chicko,” because of his reputation for “chasing the chicks.” It was always intended to be pronounced as “Chick-o,” but at some point the “k” was dropped from the spelling, rendering it as “Chico” and resulting in many people pronouncing it “Cheek-o.” Although the Brothers used the original pronunciation, when people called him “Cheek-o,” the man himself never bothered to correct them. He happily answered to both.

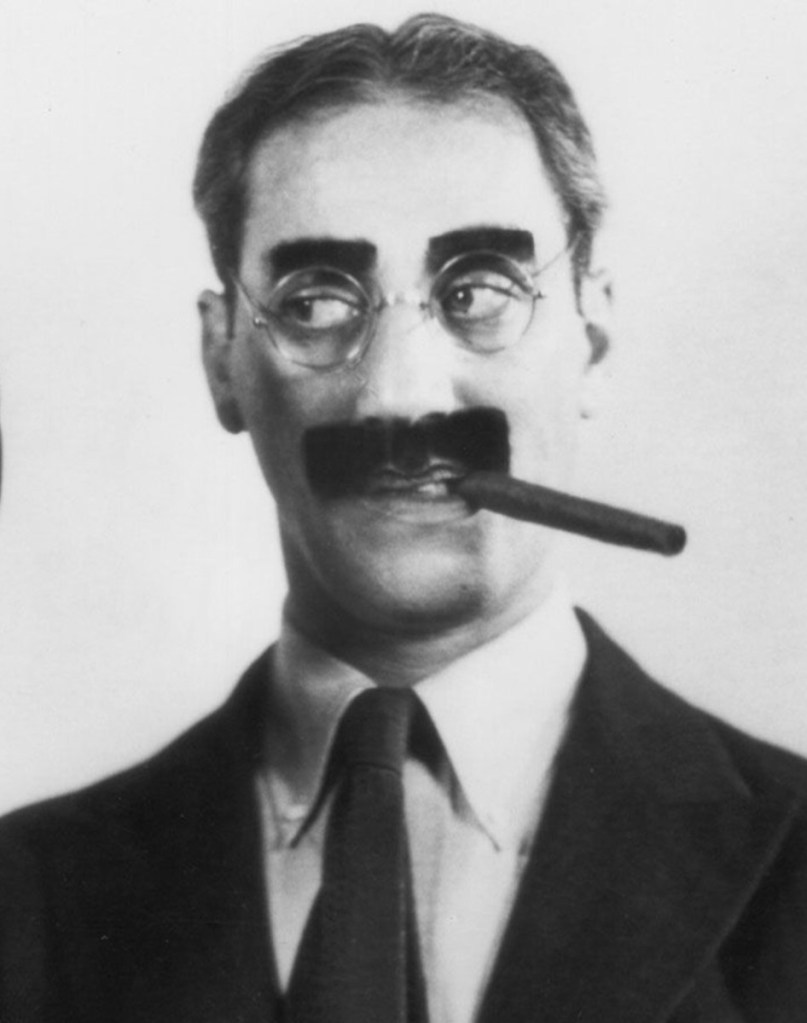

There is some speculation that Julius’ new name — “Groucho” — may have come from the fact that he kept his cash in a “grouch bag,” which was a small drawstring pouch worn around the neck to prevent the petty theft that was a fact of life in a vaudeville touring company. But more likely, as even Julius admitted, it was because he was often in a surly mood and had a cynical overall attitude.

Art Fisher had made his impact on entertainment history, and promptly vanished. No researcher has ever been able to dig up exactly who he was or what became of him. (The blog From the Marxives has identified a vaudevillian named Art Fisher performing a “cowboy mimic” act, but he pretty much disappears from the record after 1912.)

Even though it was intended as a momentary card-game joke, the Brothers were delighted with their new names, and began using them among themselves immediately. It was pretty funny for an afternoon. Then the days stretched into weeks and months. They persisted in using the names. Friends and family shrugged and began calling them by those names as well (even Minnie, who did not seem too bitter that her sons enthusiastically ditched the names she gave them). It would be ten years before the Marx Brothers used their new names as their professional stage billing, but to themselves and everyone who knew them, they were now and forever Chico, Harpo, Groucho, and Gummo. And that’s who they’ll be in these essays from this point forward. (Family members tended to drop the “o”s — to relatives and spouses they were Grouch, Chick, Harp, and later, Zep. Gummo remained “Gummo” in all cases. I guess calling someone “Gum” just sounded too odd.)

Continue reading