“The King’s great matter” it was called back in the late 1520s, a time when the Catholic Church was still the only church in England (although the Protestant movement was already well underway on the Continent)...

Even people who aren’t history nerds know about King Henry VIII and his multiple (i.e., six) wives. He burned through his last five wives in the final fifteen years of his life, but his first marriage lasted almost 24 years. Henry VIII of England and Catherine of Aragon had a complicated relationship to say the least.

To begin with, she was Henry’s brother’s wife first. Old Henry VII had arranged a marriage between his eldest son Arthur, the heir apparent, to the Spanish princess for her 200,000-ducat dowry. The pair were married when both were 15 years old, then Arthur fell ill and croaked eight months later. Catherine of Aragon was a widow at 16, and reported to everyone within earshot that the marriage had never been consummated. (Consummation of a royal marriage was considered a matter of state and certainly open for discussion by just about anyone.) And Henry VII definitely did not want to send back that 200,000 ducats. So he kept Catherine as his “guest” for several years until his second son, young Henry, was old enough to marry — even though it was expressly forbidden by religious law for a man to marry his brother’s wife. Still, 200,000 ducats was 200,000 ducats. A special dispensation had to be finagled out of the Pope based on the non-consummation of Arthur and Catherine’s marriage, and wedding plans went ahead.

On June 11, 1509, Catherine of Aragon, 23, married Henry, not quite 18. There was an empty chair at the ceremony as King Henry VII had died two months before. Catherine was marrying the new King of England, and the whole nation was waiting with bated breath for them to hurry the hell up and procreate already…

For the next decade or so, poor Queen Catherine produced a string of infants who were either stillborn or lived a few days or weeks at most. The lone exception was the future Queen Mary I…most decidedly not a male heir, which was what Henry believed he needed to secure the still-new Tudor dynasty’s future.

By 1525, Catherine was nearing 40 years old, and while it was still theoretically possible she could give birth to a healthy child, the reality was her track record of problematic births combined with her age meant that she was pretty much done with the whole reproduction thing. And her younger husband was clearly and publicly infatuated with one of her ladies-in-waiting, Anne Boleyn. Henry had already scored with her sister Mary, but Anne was proving a much tougher nut to crack (so to speak), refusing to pay a visit to the royal bedchamber without being properly married.

Thus began the “King’s great matter.”

Henry set about securing an annulment of his marriage to Catherine. He either believed, or told everyone he believed, that his marriage to her was cursed (and invalid in the eyes of God) because it violated the rule from the Book of Leviticus about marrying your brother’s wife. The special dispensation that allowed the marriage in the first place was now allegedly based on a mistruth — Henry avowed that Arthur and Catherine, being typical horny teenagers, did in fact consummate the marriage, and Catherine was a lying liar.

It was His Royal Majesty’s word against Catherine’s (who swore for the rest of her life she had never bedded down with Arthur). But even being a sovereign monarch, it would be difficult if not impossible to secure an annulment from the current Pope, Clement VII. At that time, the Pope was being held prisoner by Catherine’s nephew, Charles, who was doing double duty as King of Spain and as Holy Roman Emperor (and coping with the various infirmities and deformities caused by generations of enthusiastic in-breeding within the Habsburg dynasty). The Pope did not want to wreck his chances of release by booting his captor’s aunt out of her royal marriage, so the pleas from Henry’s messengers and letters fell on deaf ears. (If Charles had a verbal response, it likely would be incomprehensible and accompanied by a spray of saliva due to his enormous deformed lower jaw, referred to euphemistically as the “Habsburg lip.”)

The highest-ranking church official in England was (and remains) the Archbishop of Canterbury, who at the time was Thomas Cranmer, a Boleyn family friend and very recently an employee of the royal government, as England’s ambassador to none other than the aforementioned Charles. (One hopes he carried a good supply of handkerchiefs with him.) Henry pivoted to the Archbishop instead of the Pope to settle his great matter, and Cranmer took about ten seconds to review the case and said “Yup, your current marriage is invalid.” That was enough for Henry to marry Anne Boleyn in a secret ceremony in 1532. Catherine was stripped of her title of queen, and “banished” to a country life in retirement as “princess dowager” (based on her marriage to Arthur) with an ample allowance and a small army of servants, still loudly insisting she was Henry’s lawfully wedded wife. A more comfortable “banishment” cannot be fathomed, but I see her point. From this point on, when he mentioned her at all, Henry referred to Catherine as his beloved older “sister.” Anne Boleyn gave birth to the future Queen Elizabeth I in 1533, but no son.

Seeing that he had defied the Pope and not been struck down by a bolt of lightning, Henry spent the next year pushing a series of acts through Parliament that cut ties with the Catholic Church in Rome and established the independent “Church of England,” or Anglican Church.

Theologically, this was part of the Protestant Reformation that swept through Europe in the 1500s, setting up a variety of non-Catholic Christian churches, but the Anglican Church in Henry’s time still bore a striking resemblance to the Catholic Church. The only substantial difference was the king was in charge instead of the Pope. An entirely “new” religion was created pretty much out of pure spite, which may not be the stupidest reason to create a religion (it may not even be in the top five — see Scientology and its space aliens).

We won’t go into the fate of Anne Boleyn and the subsequent four wives here. All we need to know for our purposes is that the third wife, Jane Seymour, succeeded in producing a male heir. Edward VI became king when his father died in 1547, grossly overweight and riddled with ulcerated sores. The sickly Edward ruled only for six years, from age 9 to 15, before his own death, but during his reign his royal advisors worked hard to bring the Anglican Church more in line with other Protestant churches, who believed that all of the elaborate pomp and ceremony of the Catholic Church was inherently corrupt and blocked a worshiper’s direct connection to God. All the ornate vestments, gilded accessories, burning incense, red velvet, jabbering in Latin, and so on was considered entirely unnecessary and probably even sinful according to the Protestants.

Anglican church walls were whitewashed and stained glass was removed throughout the country in order to exude a more humble appearance. Liturgies in Latin were replaced by the Book of Common Prayer (written in English by Thomas Cranmer). Belief in transubstantiation, purgatory, praying to saints, rosary beads, and mandatory confession were all dumped. They kept the leadership structure of archbishops, bishops, and priests (referred to more as “vicars” as time went on) and a few other traditions.

Some bumps in the road aside (Queen Mary reversed England into Catholicism again in 1553, and her half-sister Queen Elizabeth switched it back to Anglicism in 1558, giving the whole country a case of ecclesiastical whiplash), the Church of England had firmly established itself as the 1500s ended.

But for some — your typical “small but vocal” minority — the Church of England’s practices were still too closely aligned with the Catholic Church, and not following the spirit of true Protestant reform as embodied by the ideas of Martin Luther and particularly John Calvin. The only way for the Church of England to provide a true path to salvation was to purge all similarities to the Catholics. To “purify” itself, as it were.

They were referred to as Puritans.

They practiced a form of “Reformed Christianity” called Congregationalism. They were technically still holding on to an Anglican identity by half a fingernail, but the reality was that the version of Christianity they established for themselves was very different from anything identifiable as Anglican. (More on Congregationalism when we get to the Salem Witch Trials. Stay tuned.)

For a still smaller minority of Congregationalists, this was not enough. To them, there was no hope to purify the Church of England. They wanted to separate from it entirely. Even the Puritans considered these guys to be overly-hardcore and unreasonable, and that’s saying something.

They were referred to as Separatists.

The Puritans and Separatists were isolated from mainstream English society, partly by choice and partly because they were just difficult to co-exist with. And if they got too outspoken with their criticism of the Church of England in a public forum (and many of them did), they could be fined or imprisoned.

The first to leave England to seek “religious freedom” were the Separatists, who began a slow trickle over to the Netherlands just before 1600. A specific group of about 300 of them, from the wonderfully-named village of “Scrooby” in Nottinghamshire, settled in Leiden in 1608. After resisting any attempt to assimilate, and terrified of their children turning away from their Separatist indoctrination and learning a more tolerant and open-minded worldview from the free-thinking Dutch (the whole reason the Separatists were welcome there in the first place), a portion of the Leiden Separatist community decided they would rather risk everyone’s lives and take a very dangerous chance on England’s brand new colonial territory in the North American wilderness.

This group of fanatical religious extremists are nowadays known affectionately as the “Pilgrims,” and still idealized in kindergartens across the country each November. They arrived after a tumultuous autumn crossing on the Mayflower near what was already known as Cape Cod in what would soon be known as Massachusetts in 1620. They established the Plymouth colony there.

To no one’s surprise but their own, most of the “Pilgrims” died in the first year.

(SIDE NOTE: The handful of survivors did in fact hold a “thanksgiving feast” the following autumn with some Native Americans attending, but — guest list aside — this was not out of the ordinary. Puritans and Separatists would have a thanksgiving feast at the drop of one of their buckled hats. Someone caught an extra fish? Let’s have a thanksgiving. Someone returned from market without getting mud on their breeches? Thanksgiving! It seemed to be their only form of release. The national holiday as we know it was not established until Abraham Lincoln did so in 1863 in gratitude for recent Union victories in the Civil War. Also, there was no turkey at the original 1621 dinner. Turkey were indeed abundant in New England, but they were wily and elusive, and no one could shoot well enough to bag one. All existing sources state that venison and seafood were the main courses. Sign me up, as that sounds much better than bland, boring turkey.)

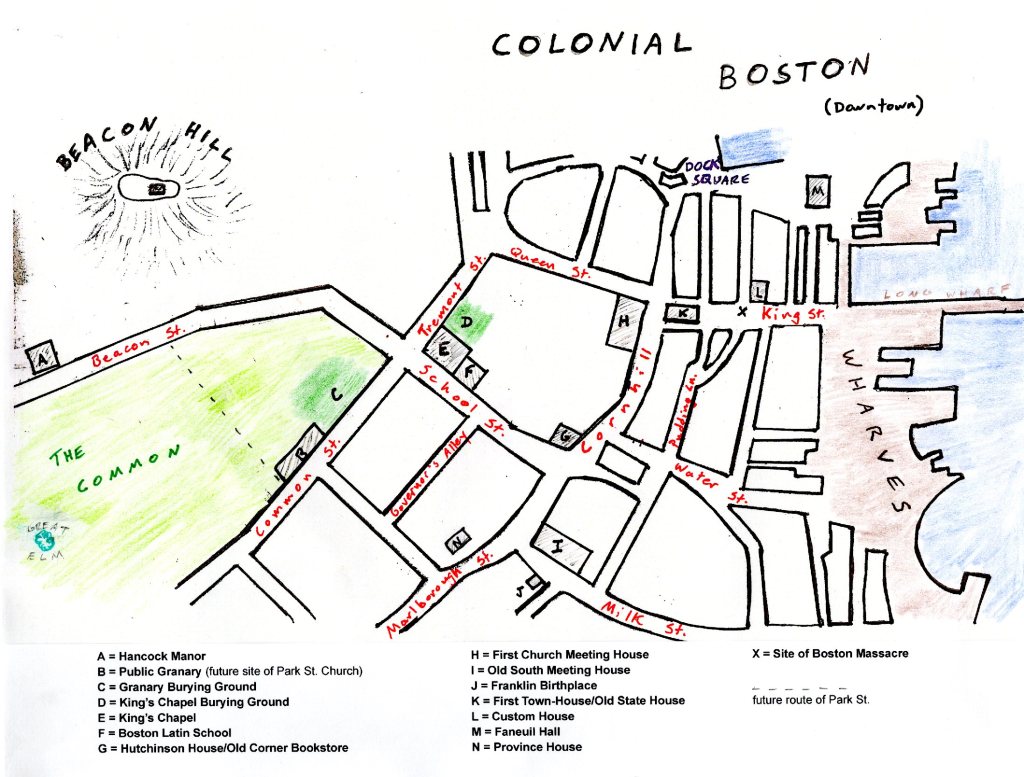

Not long after the establishment of the Plymouth colony, things got really rough for the Puritans back in England, triggering a massive wave of immigration to Congregationalist-friendly New England. The Puritans’ much bigger Massachusetts Bay Colony absorbed the Separatists’ little Plymouth. Boston was established in 1630, named after a mid-sized town on England’s eastern coast that was considered the spiritual home of the Puritan movement. John Winthrop referred to it in a speech that year “the city upon a hill” — a model city that would have the world’s eyes upon it as a shining beacon of Christian virtue.

Continue reading