The Marx Brothers, at the peak of their powers and over the course of their best Broadway shows and Hollywood films (to most fans, that’s roughly a single decade, 1925 to 1935) were an unstoppable juggernaut that essentially invented modern comedy, or maybe post-modern comedy. (Buster Keaton might share that honor, but he existed in his own peculiar silent bubble — the Marx Brothers loudly ran amok in society.)

Some have called their style anarchic. Some have said they are surreal (Salvador Dali was a big fan). Revolutionary. Ahead of their time. Anti-establishment antiheroes. They ended up as all of these things when viewed backwards through the lens of pop culture history, but they wouldn’t have called themselves any of those things at the time. They always said they were only trying to entertain. It just came out that way. And as Marx scholar Noah Diamond says, “They were never angry. They broke the rules just for the sheer joy of breaking the rules. I don’t know that they really had an agenda.”

As I put it in my one-shot Zeppo essay several years back, “the Marx Brothers were three Great Comedians — Groucho, with his cigar, painted-on mustache, and endless flow of wisecracks, insults and non-sequiturs, Harpo, the gifted silent clown who communicated through exaggerated facial expressions and horn-honking, Chico, the piano-playing sharpie with the inexplicable Italian accent — and one leftover.” (Poor Zeppo.)

For being one of the most famous and successful comedy teams in history, they were certainly the strangest. Those bizarre costumes. The fact that they worked best not as a full team, but in ones and twos (Groucho and Chico, Chico and Harpo, Groucho playing off a clueless victim of his rapier wit). The fact that one Brother was entirely unnecessary, and left the team part way through their film career with no effect whatsoever.

You can be strange, you can break the rules, you can tear down the walls of what’s accepted, but you don’t become a comedy legend unless you bring the goods. You have to be funny, and the Marx Brothers were certainly that. As proof, I submit my several years’ experience as an instructor of cinema studies…at the middle-school level. Talk about a tough crowd. I often did a semester on comedy, and always included a few of the best Marx Brothers movies. After a brief bit of skeptical silence as they adjusted to the creaky old black-and-white antiquity of what they were seeing, they would start to laugh. Yes, even the most jaded, TikTok-sated middle schooler will succumb to the charms of the Marx Brothers, if that middle schooler has at least a modicum of a sense of humor (most of them do).

In this series of essays, my plan is to explore the Marx Brothers’ entire career, but with particular emphasis on their early years and later years (hence the subtitle of “rise and fall.”) Of course, I will be touching on the classic movies that made them legends, but so many others have done that so many times (and so much better), that I feel like adding too much to that particular pile would be superfluous. The Brothers’ career peak may well be the shortest portion here. And I’ll try to avoid the most well-worn stories. Still, this will be the longest sustained piece of writing on a single topic that I’ve ever done, except for “This Used To Be My Playground” Parts 1-24, which were written piecemeal over eight years. (This still might beat that series on actual word count.) So if you’re not into the Marx Brothers, or don’t want to learn about the Marx Brothers, then I’m sorry for what’s going to be happening here for the next year or so. (Yes, it’s that long, and the site only updates once a month. I’d like to go faster, but I have a job, a life, computer games to play, golf to watch, etc.).

The problem with pursuing a straightforward examination of the Brothers’ lives and careers is that mundane facts are almost totally obscured by myth and apocrypha — mostly spun by the Brothers themselves. They were showmen, born and bred, and never let the truth get in the way of a good story. In their old age, both Groucho and Harpo wrote autobiographies that were chock full of exaggerations, mistaken memories, and outright fabrications, many of which were taken as gospel by fans and journalists of the time. It took a later generation of scholars to peel away the patina of legend and piece together as much of the real story as they could. But misinformation still proliferates, especially on the internet. As much as I can, I will use the most up-to-date, reliably researched sources. (The Holy Bee as amateur armchair researcher is greatly indebted to the legwork of these professional authors, and a full source list will be provided after the final entry of this series.) I will do my level best to get the history right, without relying on Marxian Tall Tales, and if that means there will be fewer funny stories that are only half-true (or less), then so be it. It’ll make for a slightly less entertaining read, but I’ll be able to sleep at night. (And so will you, after reading one of these essays!)

The title of this series comes from the working title of author Joe Adamson’s seminal work on the Marxes, Groucho, Harpo, Chico, and Sometimes Zeppo. (Evidently, Simon & Schuster editor Michael Korda hated cutesy, esoteric, or wordplay-based titles. Makes it fair game for the Holy Bee to swipe.)

So this will be, in a description I’ve used in the past, your typical Holy Bee mishmash. Part biography, part cultural history, part critical analysis, part rambling and musing.

Here we go…

The region known as Alsace has always been a victim of geographical tug-of-war. Hugging the western bank of the Rhine River, the area has been regarded at various times as the easternmost territory of France or the westernmost territory of Germany. In October of 1859, Alsace was firmly under the control of France, and in a Jewish commune known as Mertzwiller, Simon Marx was born to another Simon Marx (possibly spelled “Marrix”), an illiterate peddler and suspected bigamist who may have been married illegally to two women at the same time. Before the boy was twelve, the events of the Franco-Prussian War annexed Alsace on behalf of the new Imperial State of Germany — the Second Reich — and young Simon went from being French to being German overnight.

In a similar vein, before the Franco-Prussian War, the little seashore town of Dornum, just east of the Dutch border, was considered to be in the independent Kingdom of Prussia. After the Franco-Prussian War, it was considered to be in the newly consolidated German Empire. It was there, in the waning days of the old kingdom, that Miene Schoenberg was born in November of 1864 to distinctly un-orthodox Jewish parents.

Miene’s parents were Lafe and Fanny Schoenberg, who traveled through northern Germany and the Low Countries performing as a ventriloquist/magician and a singing harpist, respectively. Lafe had a reputation as a wily, philandering charmer, always on the lookout for a pretty girl or easy money, traits he would pass on to at least a few of his grandsons. The 1851 marriage of the rascally Lafe and the more proper Fanny was objected to by her parents — and had been scandalously preceded by the 1850 birth of their eldest daughter, Schontje. Schontje was turned over to Lafe’s parents to raise, and for whatever reason the Lafe/Fanny union was not blessed with any more children until 1858 — then they came very close together. In addition to Schontje, there was daughter Sara, who emigrated to New York well ahead of the rest of the family in 1872, daughters Celine (about whom nothing is known) and Jette (died at age three), and at least a few others who didn’t survive infancy. All we need to note for the future are daughter Hanchen (b. 1862), daughter Miene, son Abraham (b. 1868) and son Heinemann (b. 1873).

Fanny and Lafe, 1876, just before immigrating. Hanchen is between them, Abraham is in front of Fanny, and Heinemann is on Lafe’s lap. The fair-haired Meine is on the right.

Looking for greater opportunities, the Schoenbergs came to the melting pot of New York City between 1877 and 1879, and began the process of assimilation among the crowds of fellow immigrants in the Lower East Side. Lafe became “Louis” (although he never mastered English), Hanchen became “Hannah,” Meine became “Minnie,” and the boys, Abraham and Heinemann, became “Al Shean” and “Henry (‘Harry’) Shean.” (Fanny stayed Fanny.) Fifteen-year-old Minnie took a job in a sweatshop, assembling fur coats.

We don’t know if Schontje or Celine made the trip. If they did, it is likely they are partly responsible for the flood of “Schoenberg cousins” the Brothers remember going in and out of their household at all hours. We know that Sara married a Gustave Heymann, and had a bunch of little Heymanns roughly the same age as the Brothers.

Fanny and Lafe, 1880s

Simon Marx made his way to New York in 1880, and was taken in and apprenticed by an older cousin who worked as a tailor. He shed the name “Simon” and became “Sam,” but — although he considered himself German — he went by the nickname of “Frenchie” for the rest of his days. He never mentioned nor gave much thought to his parents and a multitude of siblings and half-siblings he had left behind in the Old Country. (“Frenchie” or “Frenchy”? Looking through all the sources, it seems to be a 50-50 split. I’ll go with Harpo’s spelling from his autobiography.)

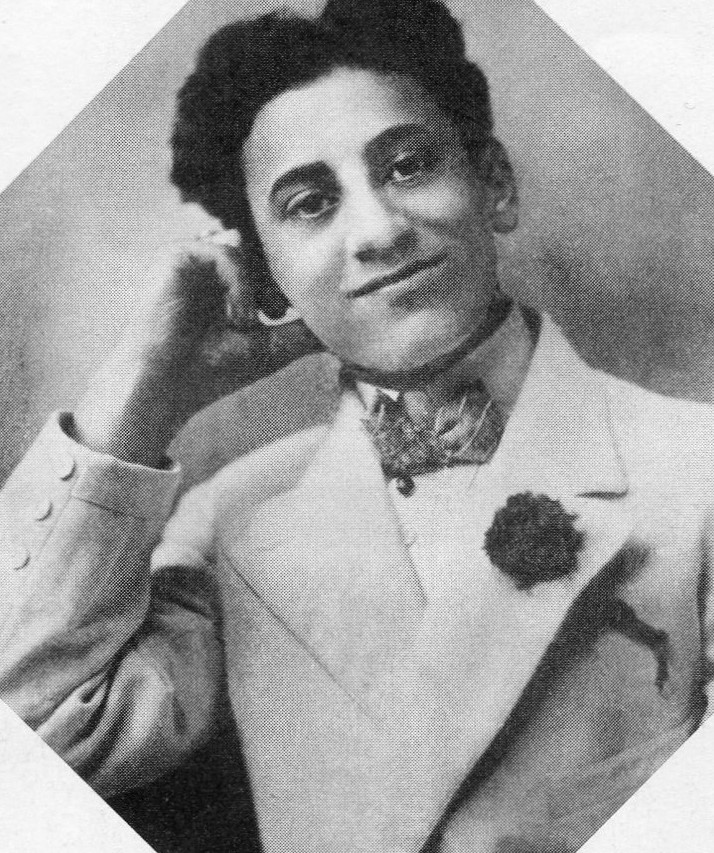

Minnie, at around sixteen years old

By late 1884 Frenchie was barely scraping by as a tailor. But there were other opportunities for a handsome, dapper, and gentlemanly young Alsatian — especially one who was a decent dancer. He picked up extra money moonlighting as an instructor at a dance hall, and that’s where he met the bright, vivacious Minnie, who had moved on from the sweatshop and was now selling straw hats. Romance blossomed, and Sam “Frenchie” Marx, 25, married Minnie Schoenberg, 20, on January 18, 1885. They bounced from apartment to apartment (always moving further uptown — away from the teeming, roughshod Lower East Side), and began to produce their remarkable offspring.

Frenchie Marx

The first Marx brother never got to be a “Marx Brother” at all. Manfred Marx, born in January 1886, was dead by July, a victim of acute “enterocolitis” (inflammation of the digestive tract) and “asthenia” (overall weakness), brought on by either influenza or tuberculosis. Whatever bacteria or virus was at fault, Manfred became another statistic in the annals of urban 19th-century infant mortality. His parents were devastated, but in true immigrant spirit, they persevered — and all their subsequent children lived to see old age.

After poor lost “Mannie” came Leonard, born on March 22, 1887. Then came Adolph on November 23, 1888. The middle child, Julius Henry, was born on October 2, 1890. Little brother Milton arrived on October 21, 1892. (He was another sickly one — Minnie watched him like a hawk.) The “surprise baby,” Herbert, was born on February 25, 1901.

We know them as Chico, Harpo, Groucho, Gummo, and Zeppo.

Although the family always had its eyes on the future, Manfred’s death was not without reverberations that would echo for years. Minnie became incredibly protective. “Sam can cough all night, and I never hear him,” she once said. “But if one of my boys coughs just once, I’m wide awake.” And the first child born after Manfred — Leonard — was undoubtedly his mother’s favorite, spoiled and cosseted unabashedly. All the boys were born with fine blonde hair (and Minnie was known to have mixed peroxide with their shampoo) — except Julius, who sported woolly black locks from the get-go. That, and the slight cast to his left eye, always made him feel like a little bit of an outsider. Minnie referred to him as der Eifersuchtihe, “the jealous one.” His brothers’ hair eventually darkened in adolescence, but for Julius, the damage was already done.

The dominant Yorkville landmark was the massive Hell Gate Brewery. The Brothers’ grandfather taught them to tell time by looking out of their window towards the brewery’s clock tower

Every Marx Brother has a story about what a terrible tailor their father was (he supposedly refused to use a tape measure, preferring to guess his customers’ measurements), and also liked to spin tales about their poverty and life in the tenements. The reality was a little different. Yes, Frenchie preferred cooking and playing pinochle to cutting cloth, but he must have been earning something. By 1895, the family had settled into the top floor of a comfortable four-story brownstone at 179 East 93rd Street in the respectable German neighborhood of Yorkville — hardly a tenement. They stayed there for almost fifteen years, a far cry from the days of fleeing angry landlords in the Lower East Side when rent came due. The Marx family was solidly lower-middle class.

Which isn’t to say the apartment wasn’t very, very crowded.

Let’s take a look at the occupants of this address, circa 1900…

The stoop of the Marx family’s building as it appears today

The occupants of three rooms on one floor of 179 East 93rd Street included Frenchie, who was more likely to be found frying short ribs and cabbage or playing cards than plying his trade. (He didn’t have a shop. His big cutting table and scraps of fabric dominated the dining area during work hours, and were put away when it was time for dinner and/or a round of cards, which came earlier and earlier in the day as he got older.) There was Louis and Fanny (now “Opie” and “Omie” to the grandsons). There was thirteen-year-old Leo and eleven-year-old “Ahdie” — towheaded troublemakers who at the time could pass as twins, and were already showing a proclivity for prowling the neighborhood looking for action. There was nine-year-old “Julie,” somewhat sour and serious, usually to be found with a book in whatever private corner he could claim, or keeping an eye on seven-year-old Milton, who was frail and small for his age. Presiding over all of this was Minnie Marx, pregnant (or very soon to be) with Herbert, and beginning to concoct the dream of putting her precocious boys on the stage. (None of the Brothers bothered with school beyond their bar mitzvah, and their attendance was pretty spotty before that.)

And according to the Brothers’ collective memories, another constant presence was a Marx Sister — Pauline (“Polly”), aged sixteen. Actually, Polly was the daughter of Minnie’s sister Hannah, born in 1884 when Hannah was between husbands, and unofficially adopted by Frenchie and Minnie to keep things respectable. (For what it’s worth, Polly was listed in the 1900 census as residing with her mother and stepfather, but who knows what the actual situation was.)

The Marxes occupied the top floor

A total of eight people — and that’s just the baseline. It seems that Polly was a semi-permanent fixture, and Aunt Hannah and her second husband Uncle Julius were there so often they might as well have been residents. Plus there was an endless stream of Schoenberg cousins, family friends, Frenchie’s customers, and pinochle players trooping up and down the three flights of stairs at number 179. And somewhere among the clutter, human and otherwise, they managed to find room for Omie’s old harp and a second hand upright piano. (One of Julius’ favorite reading spots was draped over the back of the piano.)

The story goes that Minnie was for some reason convinced Uncle Julius was sitting on secret riches, and named her middle child after him in hopes of a future inheritance. The question mark in the story is that Hannah and Julius Schickler did not marry until two years after Julius Marx was born. But who knows, maybe the couple had been “courting” for a couple of years.

Julius and Adolph in front of 179 East 93rd Street, around 1901-02

The loss of Omie Fanny in 1901 was balanced by the arrival of baby Herbert, but gradually the fourth floor got some breathing room. Polly married young, to the nearest non-related male (one of Frenchie’s card-playing cronies, actually) and got the hell out of there as soon as she could. Teenaged Leo and Ahdie were spending less and less time under the family roof, out until all hours doing who-knows.

Julius was a touring vaudeville singer by the end of 1905. And Julius most assuredly did not get an inheritance from his eponymous uncle when he finally shuffled off sometime in the 1920s. Uncle Julius’ entire estate, grouched his nephew in his colorful autobiography, consisted of “a nine-ball he stole from a pool hall, his liver pills, and a celluloid dickey.” Plus, he died owing Frenchie eighty-four dollars.

Julius, beginning to groom himself for stardom

It was the most popular form of American public entertainment from the 1890s to the 1920s. Vaudeville shows consisted of a series of short, unrelated acts (usually performed twice a day, sometimes three times a day, sometimes more) designed to give an audience a wide-ranging show at an affordable price. In a single production, an audience might see magicians, ventriloquists, dancers, musicians, acrobats, one-act plays, and plenty of vaudeville’s two most common types of performers — singers and comedians (and singing comedians, and comedic singers). Vaudeville shows toured cross-country circuits, and when one show left town after a week or so, it wouldn’t be long before another arrived.

Towards the end of the 19th century, traveling variety shows were at least a few decades old. But for many years, these performances always carried a whiff of disrepute. Often performed in saloons and beer halls, and with a flair for the risque and downright bawdy, the old version of “variety” was lumped in with burlesque, medicine shows, dime museums, and other forms of unsavory entertainment, suitable only for an audience of boozed-up, working-class men, cheering the performances through a haze of cigar smoke.

Then, some entrepreneurs (B.F. Keith and Tony Pastor foremost among them) came up with the brilliant idea of “family-friendly” variety. Wholesome entertainment, with its content strictly regulated, and the price of admission so low an entire family could attend regularly without breaking the bank. Occupying a space above seedy old-time variety, and below “legitimate theater,” vaudeville was firmly in the middle — middle-of-the-road, middlebrow, middle-class. It was really an early form of TV. The wide range of acts anticipated channel-surfing. Sit down in front of the evening’s program, turn off your mind, and relax.

Vaudeville circuits were made up of a string of theaters owned by a particular circuit company. The Keith-Albee Circuit, the Orpheum Circuit, and the Pantages Circuit were the biggest ones during the Marx Brothers’ vaudeville years. Through their imposing centralized booking offices, they operated like cartels — protecting their turf, jealously guarding their most profitable performers, and constantly trying to run the competition out of business.

By 1910, pretty much every mid-sized town across the country had a vaudeville theater (there were about 1,600 of them at this point.) And these were not small places — a typical vaudeville theater sat about 1,000 to 2,000 customers. And they were frequently filled, night after night. Many people came twice or even three times during a show’s tenure in town, akin to future generations watching reruns as comfort viewing. Vaudeville was the first example of “mass entertainment” in its truest sense.

A distinction also developed between “small-time” vaudeville and “big-time” vaudeville. “Big-time” vaudeville traveled a shorter circuit among bigger cities, and created and cultivated their “stars.” The concept of a star performer — someone who could draw a sold-out crowd on their name alone — originated with big-time vaudeville. “Small-time” was a slightly pejorative term, but also a handy technical distinction: smaller venues in smaller towns, cheap admission, and no real stars. If a performer (or group of performers) got super-popular doing small-time, the booking office would move them up. There was even a gray area called “medium vaudeville,” and that’s where Marx Brothers were firmly stuck for the first half of their time on the circuits.

On-site operations were handled by individual theater managers, who often imposed draconian rules on the performers, with complete freedom to fine them or withhold their salary if they stepped out of line. Repeat offenders would be blacklisted. Managers also filed detailed summaries and reports to the head office of how the acts were received by audiences, with possible results of a bad report being a lowering of salary, or complete dismissal.

Vaudeville was designed to enrich the circuit owners while still being affordable to audiences. The natural result was that non-star performers were paid relatively little, and their life offstage could be sheer misery. While vaudeville performances were welcome in small-town America, the vaudeville performers were still treated with disdain. Any decent establishment would turn away “show folk,” resulting in vermin-infested accommodations and meals eaten out of cans. (Food and board usually came out their salary, so only having the lowest of the low may have been a blessing in disguise.) Petty theft was a common occurrence backstage and in their cheap boarding houses, so cash and valuables would often disappear. They lived in fear of crossing one the theater manager’s arbitrary lines, and were frequently exhausted from overnight train rides (cramped into third-class, of course) from places like Ada, Oklahoma to Cedar Rapids, Iowa to face an identical set of conditions.

But for pretty much all of them, that beautiful rush they got from being onstage for twenty minutes twice a day made it all worthwhile.

It has been suggested by cultural historian David Monod that vaudeville was the most democratic form of mass entertainment. The gap between performer and audience was minimal, and it seemed that any motivated person could actually be a vaudeville performer themselves. Anyone with a little talent and a lot of ambition could find themselves on a vaudeville stage.

That’s exactly what Al Shean did.

The Marx Brothers’ maternal uncle had been a pants-presser in an East Side garment factory. As he worked his press, he often sang loudly to pass the time. His voice was pretty good, several people remarked. He should be on stage. In those days — around 1888 or so — it was almost just that easy. He joined the Manhattan Quartet and began singing at Tony Pastor’s 14th Street Theater. In a pattern that would be repeated by his nephews almost two decades later, comedy began creeping into their musical act, and by 1895, the act was renamed the Manhattan Comedy Four, and began touring the country, earning rave reviews. By the early 1900s, Uncle Al ditched the quartet and began working solo, or paired up with various comedy partners. He sang comic songs, and did little patter routines, usually in an exaggerated German accent. Audiences ate it up.

If not exactly a household name, Uncle Al was a successful professional entertainer, and that was not lost on his sister, Minnie, who also had performing ambitions — not for herself (at first), but for her sons. The Brothers remember being taken to see Uncle Al’s show whenever he was in town, but what made a bigger impression was when he paid one of his visits to the Marx apartment. He would walk up the block in his boater hat and loud suit, spats covering his ten-dollar shoes. His diamond pinkie ring flashed as he distributed pennies to the neighborhood children. Then he would hustle up the stairs and settle in for one of Frenchie’s meals, telling show business stories to the young, wide-eyed Brothers. He was a Big Deal.

As Uncle Al* regaled them, Minnie looked at her brood. Separately, they weren’t much, but together…well, they still weren’t much. But you had to start somewhere. Leo was developing into a pretty good pianist. Ahdie could pick out a couple of tunes on the keyboard as well, but not with the panache of his older brother. (Leo had had six months of piano lessons sometime previously, and was expected to pass on each week’s lesson to Ahdie.) Julie was a good singer. Shy little Milton could carry a tune when he concentrated enough not to stutter, and when prompted, was a passable dancer. One thing he wasn’t was a convincing ventriloquist’s dummy (scrawny and jug-eared as he may have been).

If family lore is to be believed (and it probably shouldn’t be entirely in this case), it was Milton who allegedly became the first Marx Brother to appear onstage, and it was under some bizarre circumstances. Evidently, the youngest Schoenberg brother, Harry Shean, was a little jealous of Al’s success, and decided to carve out a performing career for himself. Unfortunately, he had no discernible talent in any area. He decided on a ventriloquist act, and the fact that he couldn’t do a ventriloquist act wouldn’t stop him. Small-for-his-age Milton was recruited, a papier-mache dummy’s head was placed over his own, and he perched on his uncle’s lap, reciting his lines from inside the head and working the phony mouth as Uncle Harry sat and did literally nothing. Anticipating audience suspicion, Uncle Harry would jab the dummy’s left leg with a large pin. Both of Milton’s real legs had been stuffed into the dummy’s right leg. The ruse worked for a couple of performances, then Uncle Harry mistakenly jabbed the dummy’s right leg, whereupon the “dummy” yowled and hopped off stage. So much for Uncle Harry’s performing career.

Although the Brothers loved telling this story in later years, and all of them insisted it really happened, no one can remember exactly when or where it took place. (The only evidence of a performing “Harry Shean” was dug up by tireless Marx researcher Robert Bader, which indicates a Yiddish singer by that name once performed up in Ontario in October of 1899 before dropping off the face of the earth. The timing is about right, and the lone review said Shean was indeed quite dreadful, but there’s no mention of a ventriloquist portion of the act.)

Some of the Marxes, around 1904…Julius dotes on Minnie as Frenchie stares down the camera. Herbert and Milton flank the girl, who Robert Bader’s book identifies as cousin Polly, but she looks awfully young to be a 20-year-old wife. I think it’s another Schoenberg cousin (there was evidently no shortage of them).

1904…seventeen-year-old Leo had left the nest, and was honing his piano skills not with the weekly grind of lessons, but by playing for money in various nickelodeons, saloons, and pool halls. At any given time, he could be anywhere in the city, from the Bowery to the Bronx, playing barrelhouse, ragtime, and sentimental ballads — and getting better and better at it. Sometimes he went far afield, and could be found out on Long Island, or in New Jersey, or even Scranton, Pennsylvania. What little money he earned was gambled away — Leo had manifested a hardcore gambling addiction from a very early age. He also began indulging in his second lifelong addiction — sex. It was no coincidence that brothels were on the long list of dubious venues Leo was willing to play. When he got bored, or got into too much local trouble, he would move on (sometimes his “moving on” looked a lot like “fleeing”). If we discount Milton’s ventriloquist experience, and if we consider what Leo was doing to be show business, then Leo was the first Brother to earn money doing it. (Not that he ever kept a nickel in his pocket.)

The first confirmed case of a Marx Brother taking the stage for a legitimate performance is when fourteen-year-old Julius Henry became part of a singing trio in 1905. He (or more likely Minnie) spotted an ad in the New York World: “BOYS wanted for act, singers or dancers. Leroy 200 E. 22nd St.” Julius dashed downtown, and up the stairs of the listed address. To his initial surprise, Eugene Leroy answered the door wearing a flowered kimono and lipstick. The Leroy Trio featured Leroy himself backed by an ever-changing pair of young up-and-comers, and they were known to audiences — if not Julius — as a drag act. With no hesitation, Julius threw himself into the audition and won a place in the act, along with a dancer named Johnnie Morris. After two weeks’ rehearsal and a two-day train ride, Julius Henry Marx — later known to the world as Groucho Marx — made his professional stage debut on July 16, 1905 in Grand Rapids, Michigan, singing “What’s the Matter with the Mail?” while wearing, as described by Robert Bader, “a short skirt, silk stockings, high-heeled shoes, and a large, floppy ‘Merry Widow’ hat.”

Julius never expressed any misgivings about being part of such an unorthodox act, and committed to his performance like a total pro. Sadly, after a month on the road, the act collapsed when Leroy and Morris stole all of young Julius’ money (about eight dollars) and absconded into the night, leaving him stuck in Cripple Creek, Colorado. (The way he told the story later, Leroy and Morris “eloped,” but evidence suggests they went their separate ways. Both continued in vaudeville for several years, assuming correctly that their fourteen-year-old victim wouldn’t try to track them down.) He tried to earn his fare home by selling his spangled costume, then by working as a grocery delivery boy, but he could never quite come up with enough for a train ticket while still keeping his stomach full and a roof over his head. After several weeks as a Colorado resident, a sadder but wiser Julius finally had to admit defeat, and wire Minnie for the necessary funds.

He was determined not to let this bad break scare him out of show business. He eagerly grabbed whatever came his way. Before the year was out, he was back on the road as a sidekick for singer Lily Seville in an act called “The Lady and the Tiger.” Through the first half of 1906, he was part of the large ensemble song-and-dance show put on by impresario Gus Edwards, known as “Gus Edwards’ Postal Service Boys,” which worked up and down the eastern seaboard. The latter half of that year saw him acting a small non-musical part in a four-act melodrama called The Man of Her Choice. He ushered in 1907 with a return to singing and dancing in “Ned Wayburn’s Side Show.” When he had time between touring jobs during this period, Julius sang in neighborhood beer gardens for tips.

What did all of these disparate acts have in common? All of them were procured and arranged for Julius by his mother. She was now no longer Minnie Marx, housewife. She was Minnie Marx, theatrical agent and talent manager.

Her next big plan was to get another one of her sons in on the act. Her eye landed on the nearest one — shy, stuttering Milton.

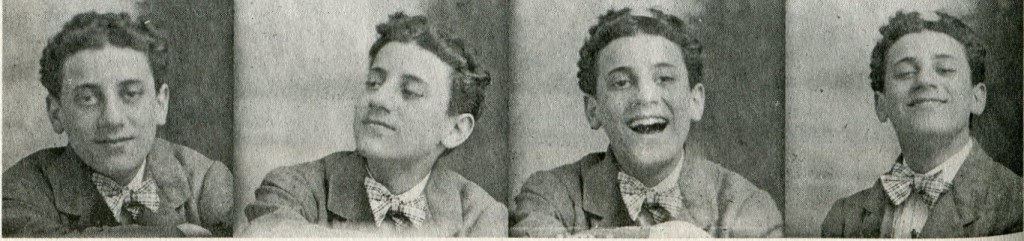

Several poses from Julius, Rockaway Beach, 1906

* although he was later eclipsed by his movie star nephews, Uncle Al remained in show business for the rest of his life, peaking in the 1920s as part of the comedy duo Gallagher & Shean, whose famous song “Mister Gallagher and Mister Shean” created the catchphrase “Absolutely, Mr. Gallagher? Positively, Mr. Shean!” that lingered in people’s memory well into the latter half of the 20th century

A little addition, when acting as the brothers’ manager, Minnie Marx went by the name Minnie Palmer and was known to be “Chicago’s only lady producer.” She also had other acts besides the Marx Brothers, like “Minnie Palmer’s Six American Beauties,” “Minnie Palmer’s Golden Gate Girls,” “With the Lord After Twelve O’Clock at Night,” and starting the “Society Sextet” in August 1913. Interestingly, the leading lady in the brothers’ show of 1912 (Fun in Hi-Skool) was Johanna Palmer (stage name Lilly Brown) who retired then. (Player, organ of the White Rat union).

Dear holy bee, as a long time Marxist of the Groucho kind and avid reader of most of the available literature about the phenomenon, i can only say: wow! your article series is probably the most detailed one i’ve seen, and also written in a very entertaining way! My hat is of to you!

just a small remark regarding the german/alsatian heritage of the family and the language connections you mention:

As you say, Frenchy came from the Alsace (not so far from where i live) and Miene came from Dornum at the coast of the north sea. But: “Plattdeutsch” is the dialect spoken in Minnies home, not in the alsace; The alsatians speak the Alsatian dialect which belongs to the Alemannic langauages and are about as far apart from each other as two german dialects can be 🙂

Thanks for the info! I will update…

I would like to ask you, what is the name of their movie which ends in a harbour where an orchestra is playing on a large yacht / ship. Groucho comes along and unties the mooring ropes and the yacht drifts out to sea with the Conductor still conducting and the orchestra playing.

I have seen the film and thought the ending, as with many Marx Brothers films, hilarious. But I cannot recall the film’s title.

Please let me know the film title.

Hoping for a reply, assuming you can assist.

Regards and Thank You for your time.

Lawrence Curtis.

(Marx Brothers Fan).

That would be 1939’s At the Circus.

Thanks for reading!