Since yesterday was all about Westminster, today would be dedicated to the City of London, often referred to as just “the City,” or “the Square Mile.” Although the oldest part of metropolitan London, most of buildings in the City are relatively new. The succession of buildings that were once here — the old Roman forum and amphitheatre, the Saxon halls, the dark-beamed wooden houses and shops of the Tudor era — are all long vanished. In their place are the sleek skyscrapers of big business. The City is London’s financial center.

The City

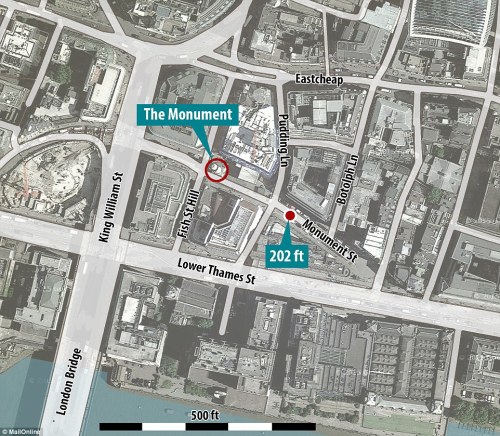

As we emerged from the Monument tube station that morning, we came face to face with the station’s namesake — the Monument of the Great Fire of London.

The fluted Doric column made from white Portland stone looms over the intersection of Monument Street and Fish Street Hill. The inside has a narrow spiral staircase, and there is a viewing platform near the top. The very top is capped by a gilded urn of fire. If the column were to be tipped over on its side to the east, the urn’s flames would be resting on the starting place of the fire, exactly 202 feet away.

Pudding Lane has shifted slightly west during various redevelopments over the centuries. It used to cross the red dot.

That empty patch of Monument Street (marked with an X in the photo below) was once a baker’s shop on Pudding Lane belonging to Thomas Farriner, who made hardtack for the Royal Navy. He extinguished his oven fire when he closed for business around nine o’clock Saturday night. His daughter Hanna checked the oven around midnight, and later swore it was cold. Shortly after that, in the dark pre-dawn of the morning of September 2, 1666, the ground floor filled with smoke, and flames began licking the wooden ceiling beams from a fire in the upper portion of the chimney. Farriner and his daughter escaped by climbing onto an adjoining roof. Their maid was not so lucky. Soon the building was engulfed. Before dawn, a strong wind picked up from the east.

London was a tinderbox. There was little open space. The buildings all abutted each other, and were all made of wood and lath & plaster, many with thatched roofs and straw flooring. Nearby warehouses were filled with timber, oil, hemp, tar, flax, pitch, coal and all manner of handy fuel. The previous July and August had seen a low amount of rainfall, so everything was brittle and dry. If the City were set up by arsonists for deliberate destruction, they couldn’t have done a better job.

As the sun rose, the fire had already engulfed its first church, St. Margaret’s, on the site where the Monument now stands. People were beginning to panic, but London’s Lord Mayor hesitated, at first dismissing it as such a minor conflagration that “a woman might piss it out” (delightfully direct were those pre-Victorians), but he soon had to eat his words. Londoners packed what they could and streamed out of the city.

In the days before professional fire departments, putting out fires came down to volunteers. Every parish church had fire fighting equipment on hand: usually brass syringe-like “squirts,” leather buckets, and massive hooks for pulling down houses. Water in large quantities was often scarce, so the primary strategy for halting the progress of fires was to create firebreaks by pulling down unburned houses and shops. The owners of said structures were understandably reluctant to destroy their perfectly good buildings (even if they were right in the path of the fire), so it was a real test of their civic-mindedness. Bucket brigades were formed to get water from wells and pumps to areas under the gravest threat.

Imagine a volunteer firefighter’s surprise when he looked up and saw that the person passing him the bucket was none other than King Charles II himself. The normally lazy and dissolute monarch stirred himself off his velvet cushions in Whitehall Palace and headed to the City, where he began supervising, issuing orders, working the bucket brigades, and generally demonstrating the kind of leadership he had been unwilling to apply in most other situations. He certainly came out of it looking better than the Lord Mayor.

Fed by strong winds, and creating its own diabolical atmosphere as major fires do, the towering flames spread, unchecked, to the west at a pace of about thirty yards per hour. Thunderous booms and cracks echoed across the city as buildings imploded. By the third day, the fire had reached St. Paul’s cathedral. Only the stone walls were left standing. The lead from the roof ran in molten, glowing rivers down the street like volcanic lava. All the buildings on the north side of London Bridge were destroyed. Dense smoke spread over a fifty mile area.

By the fourth day, the fire’s westward progress caused people to think about protecting Whitehall Palace, and it was even conceivable that Westminster was under threat if the winds continued. The Royal Navy began using gunpowder to blow up buildings between Somerset House and Whitehall. Other firebreaks began finally seeing success as the winds died down. The fire consumed all available fuel. It was completely out by the end of the week, but the ground remained hot to the touch for days afterwards.

The face of London was permanently changed. St. Paul’s was reduced to its exterior masonry walls. What was once a crowded, thriving, essentially still-medieval city was now an ashy wasteland. The lone familiar structure was the Tower of London, behind stone walls upwind and east of the fire, so it was spared. Of the 448 acres within the City walls, 373 acres were wiped out, and 13,200 houses and 87 churches were no more.

Engraved map of London just after the fire. The non-burned areas reflect the building denisty that used to be city-wide.

Luckily, the Monument that now stands near the fire’s starting place does not commemorate a large loss of life. Fewer than ten people are (officially) reported to have died, including the Farriners’ poor maid. But over 80,000 were now homeless. The very first insurance company, the Fire Office, was founded the next year. As re-building began, Charles II issued a royal proclamation: all new buildings in the City of London were to be of brick or stone. Architect Sir Christopher Wren became the busiest man in England.

The Monument itself (designed by Wren) was part of the rebuilding program, completed in 1677. In the aftermath, it took some time to pinpoint the cause of the fire. Many in the City assumed it was arson perpetrated by the Catholics, and in fact the original Latin inscription on the Monument made some disparaging comments about “popery” that weren’t removed for almost two hundred years, long after the cause was determined to be accidental. More on that in the next entry…

We didn’t linger long at the Monument, but headed east down Lower Thames Street toward the Tower of London. The Tower of London is actually a conglomeration of several towers (20 altogether) and other buildings, built at different times for different reasons. The centerpiece is still the original tower, known as the “White Tower,” the most imposing and impressive building Londoners of the 11th century had ever seen. The White Tower was built by William the Conqueror, beginning around 1078 and finished by 1100. Originally located right where the easternmost section of the old Roman wall met the Thames, the White Tower anchored what William intended to be a strong defensive position for his newly-acquired territory. By God, these Normans built castles, not the humble little halls and motte-and-bailey forts that littered the Anglo-Saxon landscape.

The White Tower, 1400s, with the London Bridge in the background.

Most of the other buildings in the Tower complex were added during major expansions ordered by Henry III and his heir Edward I from the the early 1200s through the early 1300s. Thick “curtain” walls went up on the west and north, and replaced the crumbling Roman wall to the east. Rings of small fortifying towers were built as added defense. Each ring was separated by open spaces and pathways called “wards.”

The Tower was no longer used as any kind of royal residence by the early 1500s. It became more of a defensive “keep” — a fort, a meeting place, the Royal Mint (until 1812), an armory…and a prison, which increasingly darkened its reputation. Although no great foreign armies invaded England’s shores after William’s 1066 conquest, there were enough civil wars and local rebellions to keep the Tower’s defenses busy for hundreds of years.

As far as “newer” construction and additions, the cluster of Tudor buildings known as the Queen’s House was built in the 1540s as lodgings for the Tower’s chief constable. It was not, as many websites state, built for Anne Boleyn, who would have been too dead to enjoy it by the time it was constructed. A set of Tudor storehouses north of the White Tower were replaced by an army barracks known as the Waterloo Block in the 1840s. Other Victorian-era buildings now line the eastern wall.

The Tower as it exists today. Refer back to this diagram as you read. You may need your reading glasses, but it will come in handy.

There are two chapels, one built into the interior of the White Tower (St. John’s) and one next to the Waterloo Block (St. Peter-in-Chains).

The western Tower wall as seen from the entry plaza. The rounded portion is Beauchamp Tower.

The current entrance for the Tower’s visitors is through the wetsern gatehouse known as Middle Tower. Dating from one of Henry III’s expansions in the 1200s, it was re-surfaced with Portland stone in 1717, and had the coat of arms of George I added above the arch. The iron portillicus is long gone, but the grooves where it once rose and lowered are still visible.

The Middle Tower

Another defensive feature, known as a “barbican,” also once guarded the approach to the Tower. (The barbican was the “first tower” before you reached the Middle Tower.) The rounded interior of the barbican became home to the Royal Menagerie, and the structure was later known as Lion Tower.

The Royal Menagerie began when the Frederick II, the Holy Roman Emperor, presented Henry III with three leopards in the 1230s. Lions were soon added, along with jackals, owls, a polar bear (who would go fishing in the Thames, attached to his pen by a long chain), brown bears, hyenas, and assorted others. They were housed in wooden pens lining the inside wall of the barbican. James I added a small exercise yard and an audience platform, and the inhabitants of London could view the animals for a small fee. The English climate and the cramped conditions were not conducive to good health for most of these creatures, so there was a pretty frequent turnover, but monarchs did not seem to have any trouble acquiring fresh specimens of exotic beasts, especially once Britain became an empire. (An American mountain lion was described by one chronicler as “an Indian cat from Virginia.”) It was finally decided to move the animals to the newly-opened London Zoo in 1831. The only animals to remain behind are the well-known Tower ravens, who now freely hop around the walls and lawns (their wings are clipped), and retire to a spacious aviary at night.

Wire-mesh lion sculpures peer at the remains of the Lion Tower. The moat bridge between Middle Tower and Byward Tower is in the background.

The Lion Tower was pulled down not long after the departure of the animals. Its crumbled foundation and the pit that once housed the drawbridge gears were still visible off to our left as we approached the ticket takers of Middle Tower. Once we passed through the Middle Tower, we followed the footbridge that crossed the moat. The moat is now waterless, a wide expanse of green lawn marking where it once existed. With the moat behind us, we entered Byward Tower, the true entrance of the Tower of London.

Crossing the “moat” into Byward Tower

I plugged into my audio tour (available at almost every major site in London, sometimes for free, sometimes for a small fee — it’s worth it) and headed through one final archway into the Inner Ward. Continue reading

The building that now has official claim to the “221B” address according to the London Post Office is a little further up the block, at what would ordinarily be about 239 Baker Street. It is the Sherlock Holmes Museum, and is housed in an 1815 townhouse whose exterior had the good fortune to actually look quite a bit like the residence described in the Holmes stories. The Sherlock Holmes Society of England got hold of it, meticulously recreated the interior as Doyle imagined it, stuffed it full of artifacts and memorabilia, and opened it to the public in 1990. It was still closed at seven on a Saturday morning, of course, so I walked on.

The building that now has official claim to the “221B” address according to the London Post Office is a little further up the block, at what would ordinarily be about 239 Baker Street. It is the Sherlock Holmes Museum, and is housed in an 1815 townhouse whose exterior had the good fortune to actually look quite a bit like the residence described in the Holmes stories. The Sherlock Holmes Society of England got hold of it, meticulously recreated the interior as Doyle imagined it, stuffed it full of artifacts and memorabilia, and opened it to the public in 1990. It was still closed at seven on a Saturday morning, of course, so I walked on.

of the Nerds

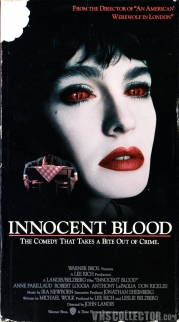

of the Nerds The trailer machine was a big console with a video screen, where customers could cue up a preview for an upcoming movie by pushing a button. If no one was around to push the button — and very few people exercised this option — the machine would simply cycle through all its trailers on a randomized loop. The problem was, the machine was loaded with far too few trailers, and each one would crop up every fifteen minutes or so. The first two lines of Sinatra’s “That Old Black Magic,” which opened the trailer of John Landis’

The trailer machine was a big console with a video screen, where customers could cue up a preview for an upcoming movie by pushing a button. If no one was around to push the button — and very few people exercised this option — the machine would simply cycle through all its trailers on a randomized loop. The problem was, the machine was loaded with far too few trailers, and each one would crop up every fifteen minutes or so. The first two lines of Sinatra’s “That Old Black Magic,” which opened the trailer of John Landis’