The Dark Universe

The massive success of Disney’s “Marvel Cinematic Universe” over the last decade has sent at least two other studios scrambling to emulate what seems to be a license to print money. They thought it would be easy. Simply utilize pre-established characters — to which they already owned the rights — in a series of interconnected, crowd-pleasing action movies with A-list stars. Well, Warner Brothers soon discovered it’s a lot trickier than it seems. Warner Brothers owns Marvel’s big comic book rival, DC, but their attempt to spin Batman, Superman, Aquaman and the like into their own cash cow has had its stumbles. Poor scripts, lack of a consistent point-of-view, and just plain clunky filmmaking have kept Warners’ “DCEU” series firmly in the shadow of the MCU. Oh, they make money, but they just don’t delight people the way the Marvel movies do. Determined to keep trying until they get it right, Warners is seven films deep as of this writing, with five more in the pipeline.

They fared better than Universal.

Universal logo, 1927-36

It occurred to Universal that they were sitting on a bunch of characters whose fame, or at least recognizability, was equal to the comic book heroes and villains of Marvel and DC: their classic stable of monsters from the 1930s, when Universal invented the American horror movie, and Dracula, the Wolf Man, the Mummy, and Frankenstein’s Monster ruled the cinema screens.

It seemed like a stroke of genius. No one really watches those movies anymore, except pop-culture bloggers and elderly cinephile cranks (the sort of people who complain about modern movies, often with enthusiastic use of the caps lock, in their five-star Amazon review of something like The Invisible Man’s Revenge — “so much better than the DRECK they put out these days!!!!”) But the names and visages of their monster characters are deeply imprinted in the popular consciousness. If you ask someone to draw a picture of Frankenstein’s Monster, they will inevitably render a likeness of the square-headed creature with bolts in its neck, as designed for the 1931 film. Ask that same person if they’ve actually seen the film, and they will likely say no. So with most people remembering the monsters, but few remembering the films themselves, the writers and directors of the potential new movies had a pretty big sandbox to play in, with pre-tested characters to sweeten the deal.

The Dark Universe was born.

It would kick off with The Mummy in the summer of 2017, starring Tom Cruise as the Rugged Hero combating a female mummy (Sofia Butella), occasionally aided by Russell Crowe’s Dr. Jekyll, portrayed here as a member of the top-secret monster-killing organization “Prodigium,” and only occasionally turning into Mr. Hyde. Following The Mummy would be The Bride of Frankenstein (bypassing the introduction of the Monster — everyone knows his origin story anyway), and after that would be Johnny Depp as The Invisible Man. And that was just the beginning. Dr. Jekyll and Prodigium would be the linking device between all the films, a la Marvel’s Nick Fury.

Then The Mummy came out — and was howlingly bad. The action was incoherent, the horror elements were laughable, and the characters were cardboard cut-outs existing mostly to spout paragraphs of expository dialogue. It was the cinematic equivalent of a dumpster fire, and barely broke even at the domestic box office. It skulks around at a 16% Fresh on Rotten Tomatoes.

horror elements were laughable, and the characters were cardboard cut-outs existing mostly to spout paragraphs of expository dialogue. It was the cinematic equivalent of a dumpster fire, and barely broke even at the domestic box office. It skulks around at a 16% Fresh on Rotten Tomatoes.

This is not what franchises are built upon.

Project co-runners Alex Kurtzman and Chris Morgan dropped everything and backed away, hands up. The Bride of Frankenstein has been placed on indefinite hiatus. The now Depp-less Invisible Man was quickly rewritten to focus on the female victim (Elisabeth Moss) and is on track for a March 2020 release, but has severed all ties to the Dark Universe. (Dark Universe? What Dark Universe?) The office on the Universal lot dedicated to the project was abandoned last year, its potted plants re-distributed, and framed posters of the old films taken off the walls where they had just been placed the year before.

To be fair, Universal didn’t do it particularly well the first time around, either, but at least they got more than one film into their world-building. Decades before the concept of a “shared cinematic universe” was even in the cultural vocabulary, one 1943 film — Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man — established the two towering icons of horror as existing together, and the first shared universe was born. Two more sequels (House of Frankenstein and House of Dracula) ran with the concept, but by then Universal was not interested in giving their horror films the time, money, and talent they had lavished on the classier 1930s films. The two Houses were B-grade sausage-factory product.

We will examine the dwindling quality of the original series in good time. For now, let’s begin at the beginning. It’ll be the usual Holy Bee mash-up of things you know (“Frankenstein” is the name of the doctor, not the monster), things you maybe don’t know (early sound pictures did not have scores because filmmakers feared the audience would be confused about where all the music was coming from if no orchestra was visible on screen.) And parenthetical asides. So many parenthetical asides.

The Birth of Universal Horror

In 1905, German-Jewish immigrant Carl Laemmle was a bored clothing store manager in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. On a trip to Chicago, he noticed lines around the block to experience the “nickelodeon” — a primitive movie theater showing a variety of short films, or offering single-viewer Kinetoscope machines. Inspired, Laemmle decided this would be the new direction of his life, and in less than five years he and several partners had founded Independent Moving Picture Company (IMP) of New York. In 1912, he moved operations to California, and turned IMP into Universal Pictures.

In 1905, German-Jewish immigrant Carl Laemmle was a bored clothing store manager in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. On a trip to Chicago, he noticed lines around the block to experience the “nickelodeon” — a primitive movie theater showing a variety of short films, or offering single-viewer Kinetoscope machines. Inspired, Laemmle decided this would be the new direction of his life, and in less than five years he and several partners had founded Independent Moving Picture Company (IMP) of New York. In 1912, he moved operations to California, and turned IMP into Universal Pictures.

Setting up shop on 230 acres of former ranch property in the San Fernando Valley he dubbed “Universal City,” Laemmle created the first entirely self-contained film production facility. By the early 1920s, Laemmle had bought out all of his partners and had sole control of the studio. But “Uncle Carl” may have overreached himself. As his nickname indicated, shameless nepotism was rampant at the studio. (“Uncle Carl Laemmle/Has a very large faemmle” ran one bit of Ogden Nash doggerel.) Countless cousins, nieces, nephews, and in-laws were on the payroll, many doing nothing but occupying studio bungalows. The other issue causing problems for Universal was the fact they did not own their own chain of theaters like most other major studios did. Universal was forced to rely on independent exhibitors, which ate into profits. By the beginning of the Great Depression, the studio was in deep financial trouble.

Then a few things happened to stave off disaster. Uncle Carl had retired and turned over control of the studio to his son, Carl Jr., in 1928. Junior Laemmle demonstrated more enthusiasm than administration skill, but he had a good instinct for stories that would work well on film. One of the first productions he oversaw was the anti-war drama All Quiet on the Western Front (1930), which was a huge success both financially and artistically, winning the Academy Award for Best Picture and Best Director (Lewis Milestone). The cinematographer, Karl Freund, was a veteran of post-war German Expressionism and first genius of the field. Junior also had the inkling of an idea that had been rattling around his head for a couple of years — can a film be made that combined a literary pedigree with the ability to sustain a mood of tension and terror all the way through? It wasn’t necessarily an original idea. Universal itself had already (mostly) achieved that alchemy with 1925’s The Phantom of the Opera.

control of the studio to his son, Carl Jr., in 1928. Junior Laemmle demonstrated more enthusiasm than administration skill, but he had a good instinct for stories that would work well on film. One of the first productions he oversaw was the anti-war drama All Quiet on the Western Front (1930), which was a huge success both financially and artistically, winning the Academy Award for Best Picture and Best Director (Lewis Milestone). The cinematographer, Karl Freund, was a veteran of post-war German Expressionism and first genius of the field. Junior also had the inkling of an idea that had been rattling around his head for a couple of years — can a film be made that combined a literary pedigree with the ability to sustain a mood of tension and terror all the way through? It wasn’t necessarily an original idea. Universal itself had already (mostly) achieved that alchemy with 1925’s The Phantom of the Opera.

Straitlaced America struggled to get its own take on the horror genre off the ground. Cosmopolitan European filmmakers had been more daring, thrilling audiences with creepy fare such as The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) and the vampire tale Nosferatu (1922). It was assumed by conservative American studio heads and theater owners that those sorts of horrific tales would be at the mercy of local film censor boards, be bad for public morals, and cause more controversy than they were worth. But they ignored evidence right before their eyes. A 1920 adaptation of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde starring John Barrymore definitely had some horror elements, and it made truckloads of money. People flocked to see Universal’s own The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) not for the melodramatic Gothic romance that it was, but for the hideously grotesque make-up that actor Lon Chaney devised for his version of the hunchback.

By 1925, American audiences seemed ready for a true horror movie. Universal, at that time still under the guidance of Uncle Carl, gave it to them.

The Phantom and Lon

Uncle Carl bought the rights to the 1910 novel The Phantom of the Opera by Gaston Leroux directly from the author on a trip to Paris in 1922, with a plan to turn it into a vehicle for Universal’s favorite specialist in the grotesque, Lon Chaney. Laemmle spared no expense, building a massive recreation of the Paris Opera House interior inside Universal’s Stage 28, along with the Phantom’s lair among the labyrinthine tunnels and sewers underneath. Early Technicolor was used in a few key sequences, such as when the Phantom appears as “Red Death” at the masquerade ball.

It was a troubled production, with extensive re-shoots and re-edits, but the final product that went into general release in November 1925 left an indelible impression on audiences, almost entirely due to Lon Chaney’s horrific appearance. Continue reading

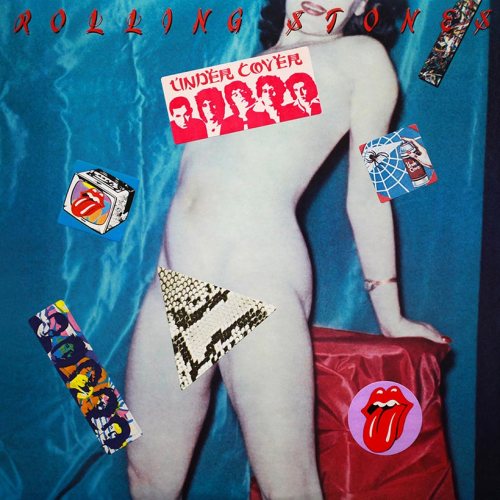

Blood” is the last gasp of the Stones’ side job of creating at least one dance track per album for the discos, a tradition that began with

Blood” is the last gasp of the Stones’ side job of creating at least one dance track per album for the discos, a tradition that began with

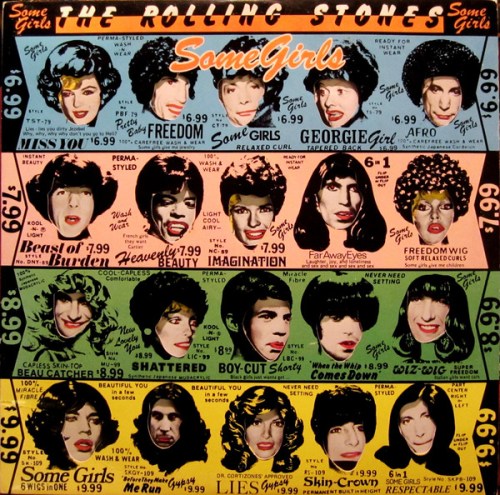

at Pathe-Marconi with an empty tank. No songs, no ideas for songs, no lyrics, no scraps. He had used it all up on his own album,

at Pathe-Marconi with an empty tank. No songs, no ideas for songs, no lyrics, no scraps. He had used it all up on his own album,

Thompson, specifically to work with her father, Henry, on it. The story reflected their own difficult relationship. Location filming on

Thompson, specifically to work with her father, Henry, on it. The story reflected their own difficult relationship. Location filming on