PRODUCER: Can you get some more variety into your part?

ZEPPO: How many different ways are there to say “yes”?

(Allegedly overheard during Animal Crackers Broadway rehearsals, 1928.)

“Zeppo Marx is a peerlessly cheesy improvement on the traditional straight man.” — James Agee, legendary film critic.

“Oddly enough, it proved to be Zeppo who was the most difficult to track down in terms of his post-team life. Perhaps if I had more time and money…though I expect that would have a pretty minority appeal.” — Simon Louvish, Marx Brothers biographer.

One thing that comes from a reading list like mine that consists mostly of biographies is you get a glimpse of the difference between a well-known person’s public image and what he is like out of the spotlight. A seemingly simple, straightforward persona can hide immense depths of complexity (and vice versa).

It seems clear that no one is ever likely to write a biography of Zeppo Marx, the fourth Marx Brother and one who proved entirely superfluous and inessential to the act. [2024 Edit: I was wrong.] So much so that he dropped out halfway through their film career and barely anyone noticed. Zeppo, with his entirely normal appearance and lack of any sort of comedic character, has always been described as the “straight man,” but the Marx Brothers never really needed a straight man, at least as that term is normally understood. Their aggressive form of comedy took on authority, pretension, and stuffiness — external targets, which did not require a traditional straight man within the team feeding them set-up lines. And Margaret Dumont was the greatest straight woman in cinema history when one was needed. The Marx Brothers were three Great Comedians — Groucho, with his cigar, painted-on mustache, and endless flow of wisecracks, insults and non-sequiturs, Harpo, the gifted silent clown who communicated through exaggerated facial expressions and horn-honking, and Chico, the piano-playing sharpie with the inexplicable Italian accent — and one leftover.

The leftover has become a footnote in film history, and perhaps nothing more than a mostly-forgotten cultural punchline. “Zeppo” has become a euphemism for “unneeded.” So, who was Herbert “Zeppo” Marx, outside of his limited screen persona? This is a question that kept occurring to me as I’ve read through various Marx books and bios over the years, and Zeppo-the-real-person would pop up now and again and tug at my curiosity.

Zeppo does have his defenders, at least as a performing presence. It was an unwritten (but seemingly ironclad) rule that a musical comedy of stage or screen in the 1920s and 30s, no matter how off-the-wall or zany, had to have a romantic subplot featuring an attractive young couple. These parts are pretty bland and thankless, especially to the eyes of modern audiences, and Groucho, Harpo, and Chico were far too colorful and grotesque to play such a part. You would think that the role would fall naturally to young, relatively handsome Zeppo. In fact he has even been credited with undermining the entire nature of romantic lead, just by virtue of being a Marx Brother.

“Zeppo’s parts were always intended to be a parody of the juvenile role often found in sappy musicals of the 1920s-30s era. Sometimes, he would just have a few lines, and he would otherwise be reduced to standing in the background with a big smile on his face..and always stiff and wooden. In other films, Zeppo would have a more significant role as the romantic lead, but he would still always be stiff, wooden, and, yes, with a big smile on his face. Either way, he could never be considered a real straight man. He was a sappy distortion of the real thing, and sort of the gateway through which we connected with the other Brothers.” — Danel Griffin, film theorist, University of Alaska Southeast.

Joe Adamson goes on to say that Zeppo’s participation in the letter-dictating routine in Animal Crackers displays his obvious importance to the act. And Allen W. Ellis wrote a massive scholarly paper called “Yes, Sir: The Legacy of Zeppo Marx,” (for which I refuse to pay $35 to the Wiley Online Library for “24-hour access” to the PDF, enlightening as I’m sure it must be).

It’s nice to see poor Zeppo get this belated critical respect, but it is not backed up by what we see on the screen. By their own admission, the brothers and their writers didn’t put all that much (or any, really) thought into Zeppo’s role. The letter-dictating routine is one scene in one movie. His presence in any other comedy routine in all the other movies is non-existent. Out of the five movies he did with his brothers, in only two (1931’s Monkey Business and 1932’s Horse Feathers) did he play anything close to a romantic lead…and acquitted himself fairly well. No worse than any other person playing that type of part at that time, and certainly nothing to indicate it was even the slyest of parodies. In his other three films, he played Groucho’s secretary/assistant, with a handful of unimportant lines. Not only did those films not appear to be parodying wooden, stiffly-smiling romantic leads, they went out and got other young actors to play actual wooden, stiffly smiling romantic leads. It didn’t even seem to occur to them to fit Zeppo into that role each time, where maybe he could poke fun at its conventions from within and be a real team member.

No, he didn’t have much to do because, historically, the fourth Marx Brother never had much to do, and no one was interested in changing the long-established procedures. Continue reading

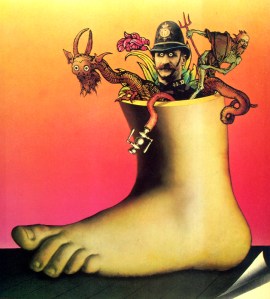

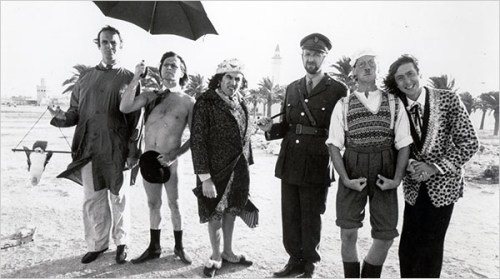

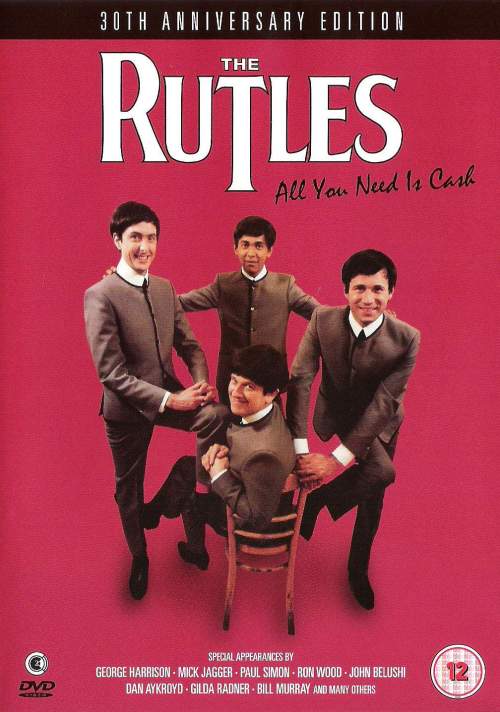

Lorne Michaels believed there was a lot of potential in The Rutles, and produced a TV movie built around them — All You Need Is Cash. Presented as a fake documentary, Cash fleshed out the Rutles “story” from inception to break-up. From the grainy black-and-white of postwar Britain, through the colorful Pop Art and psychedelic eras, and finally the dawn of the cold, gray ’70s, Cash captured the feel of a “rockumentary” perfectly. (Just as RWT foreshadowed the more well-known SCTV, Cash beat

Lorne Michaels believed there was a lot of potential in The Rutles, and produced a TV movie built around them — All You Need Is Cash. Presented as a fake documentary, Cash fleshed out the Rutles “story” from inception to break-up. From the grainy black-and-white of postwar Britain, through the colorful Pop Art and psychedelic eras, and finally the dawn of the cold, gray ’70s, Cash captured the feel of a “rockumentary” perfectly. (Just as RWT foreshadowed the more well-known SCTV, Cash beat