So that’s it for the Marx Brothers…one of the most in-depth research/writing projects I’ve ever done…I spent almost a year on it (off and on, because I do have a life, despite all evidence to the contrary), and I hope it went down OK.

Now things are going to get real Beatle-y around here for a while (casting another load of doubt on the whole “having a life” statement)…

The big question in writing an introduction to something like this is, how much does the reader already know? How much do I recap and rehash? Odds are if you’re reading this, you’re probably something of a Beatles fan to begin with and know at least the basics of their “Get Back”/Let It Be project as it fits into the overall (semi-mythical) Canonical Beatles Narrative:

1. After the tense and fractious sessions for The Beatles (universally known as “The White Album,” which I will call it from this point on) in the summer and fall of 1968, the group wanted to return to basics and do a one-shot concert of all-new material as a simple, stripped-down four-piece band, with an accompanying TV show and album, and without heavy production or a bunch of outside musicians.

2. To that end, in January of 1969 the Beatles gather for a series of filmed rehearsals on a cavernous, mostly empty soundstage at Twickenham Studios, which demonstrate the bitter atmosphere of the White Album sessions has continued.

3. A strung-out John takes little interest in the proceedings as he is totally infatuated with 1) girlfriend (soon to be wife) Yoko Ono, who attends all the sessions attached to his side, and 2) a dangerous flirtation with heroin. Paul tries to keep things on the rails and comes off as domineering. George, fed up with the lack of interest shown in his songs, and with being told what to play and how to play it by Paul, quits the band a week into the rehearsals.

4. George is coaxed back with the promise of a scaled-down version of the project. The “no outside musicians” rule is bent by adding keyboardist Billy Preston to fill out the sound (overdubs on the album are still a no-no at this stage). Preston’s good-natured presence and the conditions of George’s return have relieved a lot of pressure. Once the location switches from the dreary Twickenham soundstage to their home base at Apple, the mood improves noticeably. The sessions are quickly wrapped up, and the climactic concert is performed on the roof, out of sight of the mostly-puzzled Londoners below.

5. The songs are scheduled to come out on an album titled Get Back in the summer of 1969, but everyone is thoroughly sick of the project and its bad vibes, and it’s shelved at the last minute in favor of (temporarily) burying the hatchet in order to start work on Abbey Road, which comes out in September 1969 to universal acclaim.

Before it was cancelled, the intended Get Back album made it as far as a cover design, parodying the photo and text of The Beatles’ first British album Please Please Me

6. Re-titled Let It Be, the former “Get Back” album is heavy-handedly remixed by Phil Spector. The accompanying 80-minute documentary is edited in such a way that it seems to capture a bored band’s dissolution, and is considered depressing and dreary by just about everyone who watches it. Album and film come out in May 1970, and are viewed as the Beatles’ swan song (even though the superior Abbey Road was recorded after it).

7. About fifty years later, acclaimed director Peter Jackson wonders if there’s something in the almost sixty hours of footage captured by original director Michael Lindsay-Hogg that maybe tells a different story. He goes back, digitally cleans and brightens up the grainy old film, and pieces together an entirely different documentary that shows there were a lot of good, fun moments in those sessions, that the band members didn’t seem to hate each other, and that there was still some joy left in the Beatles’ tank.

And I just went and recapped it, didn’t I?

Speaking of recapping, one of the more underrated elements in Peter Jackson’s three-part, eight-hour documentary The Beatles: Get Back is its opening montage — succinctly summarizing the history of the Beatles in a little under eleven minutes. The rest of the documentary is given over to the January 1969 rehearsal/recording sessions, but the average viewer will find that they have been given the proper context, and the stage is set to see how these sessions play out.

I am not the average viewer. When it comes to the Beatles, I get a little detail-obsessed, as we’ll see here and in the next couple of entries.

After that short opening sequence, we are dropped in right on the first day’s rehearsal on January 2, 1969, fly-on-the-wall style, watching the band members arrive and wish each other Happy New Year. I began wondering, when did they last see each other? What happened in the relatively short amount of time between the White Album sessions and the “Get Back” sessions? What were the just-passed holidays like for them? They weren’t exactly starting this project with a bumper crop of much-needed new songs. Had they been writing? What recent experiences were on their minds when they sat down and noodled the first few notes of an embryonic “Don’t Let Me Down” on Day One?

It turns out the time between the end of recording the White Album and the beginning of “Get Back” (only about ten-and-a-half weeks!) was quite eventful, professionally and especially personally, for all of them, and is a little-explored area of Beatles history.

[NOTE: Although I’ll refer to the project as “Get Back,” that song would not be composed until January, and the sessions would not be referred to by that name until after they were over.]

In the summer of 1968, Ringo (who, of all the Beatles, seemed to have the most potential as a film actor) accepted the co-starring role in an upcoming film starring Peter Sellers, whom Ringo had known socially for some time. The film, titled The Magic Christian and based on a satirical novel by Terry Southern (who also penned the script), wasn’t due to begin shooting until late January of 1969. In hectic Beatle-time, where every day was packed, that seemed like a million years in the future. The date eventually snuck up on them, as we’ll see.

The germ of the idea of a return to live performance came from shooting a promotional film for their summer single, “Hey Jude/Revolution” at Twickenham Film Studios on September 4, 1968 in front of — and at the end of “Hey Jude,” surrounded by — a live audience.

The film was directed by former Ready, Steady, Go! director Michael Lindsay-Hogg, who had also directed the Beatles’ “Paperback Writer/Rain” promos back in 1966. For the first time since their pre-fame days, hysterical screams did not drown out the music. Their teenage fans from the old moptop era were growing older and more sophisticated, and wanted to actually listen.

Though not a fully “live” performance — they did some takes with the vocals live, but all the instruments had been pre-recorded — the filming was a nice break from the White Album sessions, and sparked a desire to do at least one real concert as soon as possible. (That desire was sparked mainly in Paul, who initally suggested popping up unannounced in pubs and small nightclubs under an assumed name. John and George immediately dismissed that idea out of hand, but were open to a single performance. It was quickly decided that the songs performed would be the debut of all-new original material, something they had never done before, which appealed to group’s sense of novelty and distaste for repeating themselves artisically.)

Preliminary arrangements and some pre-planning for the show began almost immediately at the Beatles’ new self-owned management/multi-media company, Apple Corps Ltd., located at 3 Savile Row in the heart of London’s garment district. Since original manager Brian Epstein’s death the previous year, “preliminary arrangements” and “pre-planning” were not really the Beatles’ (or Apple’s) strongest areas. Often guilty of a blithe disinterest in their affairs ouside of making music, the Beatles always expected things to just sort of fall into place — not knowing that it used to be Epstein, working feverishly behind the scenes, who made everything happen according to their whims. The concert idea aimlessly drifted around for awhile, with a few idle stabs at making specific plans. Finishing the in-the-works album was the priority.

Finishing the White Album, September-October 1968

The last time all four Beatles were together before the “Get Back” rehearsals was likely October 13, 1968 at EMI Studios in St. John’s Wood, London. (Although its address was Abbey Road, the building itself would not be officially renamed “Abbey Road Studios” until 1976.)

It was one of the last recording sessions for the White Album. The final song for the album, John’s beautiful “Julia,” was recorded that day, along with mono and stereo mixing for several songs as the album was nearing completion. “Julia” was a solo performance by John on his acoustic guitar, with none of the other Beatles performing, but as per established custom, it is almost certain they were all in the studio — once a session was underway, inspiration could strike, or a song could need a new overdub. (An EMI staff member remembers Ringo often sitting in the studio’s reception area reading a newspaper while the others worked on non-drum business. Ringo himself remembers Sgt. Pepper as “the album where I learned to play chess.” But he was dutifully on the premises if needed.)

Paul runs the mixing console as George Martin and Ringo observe, October 1968

But sometimes, a well-earned vacation just can’t wait…Ringo left on holiday the following day, October 14, which saw more mixing and the final overdubs for George’s “Savoy Truffle.”

And then there were two…with all recording officially finished, George left on business on October 16. Beginning at five that evening, and running until five the following evening, John, Paul, and Beatles producer George Martin supervised all of the final cross-fades, edits, and sequencing for the sprawling double album.

John & Paul working out the White Album running order, October 16-17, 1968

No doubt exhausted after a 24-hour work cycle, a bleary-eyed John and Paul walked out of the studio doors in the early evening of October 17 leaving a completed album ready for mastering and release. Beatle business continued whirring away at Apple, including (minimal) planning of the still-nebulous concert, but the Beatles themselves would follow their own separate paths for awhile.

Ringo…

The least busy during this “time off” was, perhaps unsurprisingly, Ringo Starr.

George’s forthcoming stomping out of the band in January became more well-known, but it was Ringo who actually quit the band first (and for almost twice as long), back in August, when he could no longer bear the arguments and dysfunction of the White Album sessions. He escaped to the Mediterranean with his wife, Maureen, and two young sons, Zak and Jason. There they were granted the use of Peter Sellers’ yacht and its crew as it cruised around the island of Sardinia. Ringo’s famous story about the yacht captain telling him about octopi (who are quite intelligent for mollusks) gathering stones and colorful shells to make seafloor “gardens,” which inspired his Beatles composition “Octopus’s Garden,” may date from this trip. (“May”? See below.) After two weeks of sunshine and reflection, and an apologetic telegram from the other three (“come on home, we love you”), he re-joined the band the day before the “Hey Jude/Revolution” filming, and subsequent completion of the White Album. (They had recorded “Back in the U.S.S.R.” and “Dear Prudence” in his absence, with the other three — mainly Paul — filling in on drums.)

Ringo had fallen in love with Sardinia, and decided to repeat the whole experience (in a happier frame of mind). He and Maureen packed up the family again and departed London on October 14. Some sources say he borrowed Sellers’ yacht once more, and the octopus story dates from this second visit. (I lean toward believing it did happen on the second trip — the way he bashfully shows off a fragment of the song during the “Get Back” rehearsals speaks to it being a new creation, something that happened while they were apart from each other.)

Ringo and company arrive at the Costa Smeralda, Sardinia, on October 14, 1968

The Starkey family returned on October 28 to face the daunting prospect of packing up and moving house.

Since the money started really rolling in back in early ‘65, John and Ringo had lived less than a mile apart, each in rambling mock-Tudor…well, not quite mansions, but certainly damn big houses, located in the exclusive St. George’s Hill area near the village of Weybridge, just under twenty miles southwest of London. The region was known as the “stockbroker’s belt” due to it being a comfortable country retreat for wealthy London businessmen. John’s house — “Kenwood” — is well-known in Beatle lore for being the site of many songwriting sessions with Paul, for the music room up in the attic where he experimented with instruments and tape reels (and various substances), and for the tiny sunroom annex where he read, wrote, lounged, and stared at the muted telly for inspiration. John had been photographed many times in and around Kenwood, despite his claims that he didn’t care much for the place, being too bourgeois and staid for his restless nature.

But John had not lived there since late June, when he decided to live with Yoko in a small flat in the heart of bustling London, 34 Montagu Square, leased by none other than Ringo. Ringo sublet the place, and served as an absentee and very tolerant landlord whose free-spirited tenants began celebrating their new love by dabbling in hard drugs. (The flat had also been used by Jimi Hendrix, so its reputation as something of a drug den already existed.) John’s soon-to-be-ex-wife Cynthia was allowed to occupy Kenwood with her mother and the couple’s son, Julian, until the divorce was finalized, which it was on November 8. She moved out, pulling up the master bedroom carpet to take with her, symbolically leaving a bunch of razor-sharp tacks jutting up from the floor.

Sunny Heights

Speaking of packing up and moving out, with John no longer around, Ringo decided it was time to move on as well, and put his own Weybridge digs — “Sunny Heights” — on the market and began looking for a new place. Enter Peter Sellers again. Like John, Sellers was going through a messy divorce and wanted a change of scene, so he sold his country estate, Brookfield House, to Ringo for a bargain “friend” price of £70,000. Brookfield was deeper into the Surrey countryside and built on a much grander scale than the relatively modest Sunny Heights. A proper historical manor house, it had acres and acres of land, a private lake, paddocks and barns, a gym and sauna, and a private cinema. As the moving vans arrived on November 19 to collect the last of his possessions from Sunny Heights, perhaps Ringo wistfully looked up the hill at an abandoned Kenwood and noted the end of an era.

Brookfield House

Kenwood wasn’t abandoned for long (more on that in the next entry).

A Beatles tradition since 1963 was the recording of a Christmas message to members of their official fan club, mailed out on a “flexi-disc.” They usually did this together, gathered around a microphone at Abbey Road, riffing on their prepared script, putting on funny voices, singing bits of songs, doing surreal skits, and generally messing around. In 1968, for the first time the messages would be recorded separately, and Ringo taped his message at some point in November.

The movie Candy, in which Ringo had a role as a Mexican gardener named Emmanuel, opened in the U.S. on December 17 to respectable box office business. Audiences were mostly lured in by the titlliation factor of seeing Miss Teen Sweden Ewa Aulin as the title character in various states of undress, being seduced by big names like Richard Burton, Walter Matthau, and Marlon Brando, all of whom (like Ringo) had relatively small parts in different sequences of the episodic film. Ringo filmed his bit way back in December of 1967, and did not participate in any publicty or promotion at the time of Candy’s release. Very much an artifact of its time, this psychedelic nugget of late-’60s softcore erotica earned decidely mixed reviews, and is today regarded as a campy cult classic. (Its U.K. release was delayed until early 1969.)

Nothing more is recorded of Ringo’s activities in 1968, but one can assume he was settling in, enjoying some quality domestic time, and having a blast exploring all the features of his massive new home, until he was summoned back to the drum stool on January 2 to begin the fateful “Get Back” sessions.

In Beatles News…

The animated film Yellow Submarine had long since come and gone from British cinemas (it was a July release), but was just about to come out in America. The Beatles had next to no involvement in its production (they filmed a very brief live-action cameo for the ending — other actors performed their voices in the main film), but they had agreed to provide four “new” songs for the soundtrack. The songs they submitted were “Only A Northern Song,” (a Sgt. Pepper reject), “It’s All Too Much” and “All Together Now” from post-Pepper summer ‘67 sessions, and “Hey Bulldog,” from the early ‘68 sessions that produced the “Lady Madonna” single. No accompanying soundtrack album had yet been issued. That situation would be — eventually — corrected to mark the American release. George Martin’s original orchestral score was re-recorded for this purpose on October 23 and 24, 1968, and “Hey Bulldog,” “Only A Northern Song,” “All Together Now,” and the previously-released “All You Need Is Love” that featured heavily in the film all received stereo remixes on October 29. None of the Beatles attended these sessions.

On November 6, the erudite and much-loved Apple press officer Derek Taylor, the Voice of the Beatles to the World in their later years, told the media that the Beatles had booked the Roundhouse concert venue in the London neighborhood of Chalk Farm for December 14 through 23 for rehearsals, a run-through, and the actual concerts, all to be done in front of an audience.

The date was soon moved to a single night, January 18, 1969, with rehearsals and run-throughs to be held elsewhere.

For several weeks in the fall of 1968, the Roundhouse was slated to be the venue for the big “Get Back” concert

The Yellow Submarine movie was released in the U.S. on November 13, 1968. The soundtrack album was held back until January 1969 to avoid conflicting with the White Album release. The Yellow Submarine soundtrack album has always been considered the bastard stepchild of the Beatles discography, as it featured only the four “new” songs, accompanied by the previously-released 1966 title song and “All You Need Is Love,” with Martin’s pleasant-but-not-the-Beatles orchestral score filling up side two. (There was talk of issuing the four new tracks and “Across The Universe” as a bonus track on an EP. It got as far as the mastering process, but was never released.)

EMI Studios at Abbey Road underwent a major technical upgrade during this time, replacing their outdated tube-based, four-track equipment with a solid-state, eight-track mixing console, resulting in a noticably different, warmer sound on the Abbey Road album which marked their return to the studio.

George…

This period was a fruitful — and sometimes fraught — one for George Harrison, who had become increasingly frustrated with the limited role he was forced to play in the Beatles. In late 1968, he saw what life could be like outside of the group he had been with since he was fifteen. He discovered what it was like not to be a permanent kid brother/junior partner.

One of Apple Corps’ many subsidiaries (and the only one that could be called truly successful) was Apple Records. For Beatles releases it was something of a vanity label, as they were officially contracted to EMI, collectively and individually, through 1976. (EMI were quite happy to slap the Apple logo onto Beatles records and still collect the profits.) But for other artists, Apple Records served as a genuine, functioning independent record label. Of the four Beatles, it was Paul and George who took their roles as Apple talent scouts, A&R men, and producers the most seriously. In its first year or so, Apple Records added artists like Mary Hopkin, James Taylor, Badfinger, Billy Preston, the Modern Jazz Quartet, and Doris Troy to its roster. But before all of them came George’s pet project — singer-songwriter Jackie Lomax, a fellow Liverpudlian who used to play in the Merseybeat band The Undertakers in the early 60s.

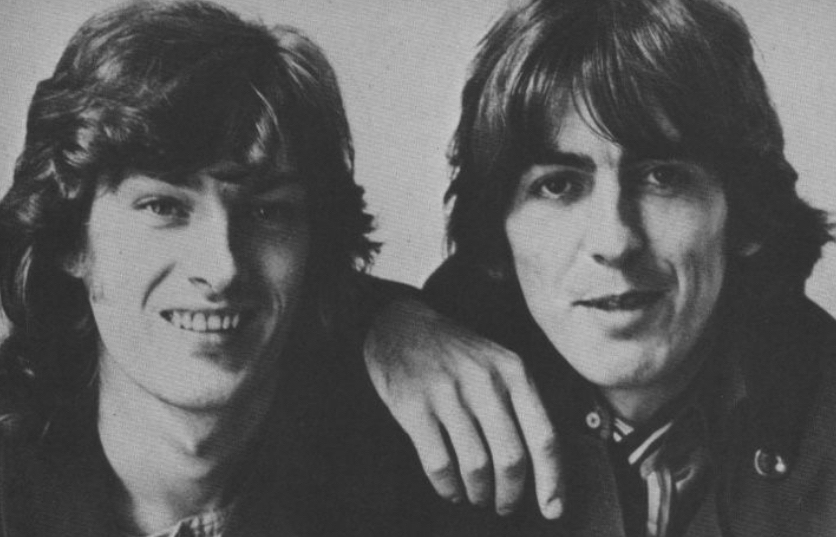

Jackie Lomax and George, Spring ’68

May 1968…The Beatles gather at George’s house in Esher (one suburb over from John and Ringo’s Weybridge) to make some demo recordings for the White Album, which was just about to start its marathon sessions. Among these demos was George’s composition “Sour Milk Sea.”

Jackie Lomax had originally been signed to Apple Publishing as a songwriter, but at some point George heard his demo tape and was impressed. Lomax became the very first outside artist signed to Apple Records. George plucked “Sour Milk Sea” from his growing backlog of songs and decided to make it Lomax’s first single.

White Album sessions had begun on May 30 — hesitantly, with lots of stops and starts as various Beatles were still running about on personal and Apple business. From June 24 to 26, George took advantage of one of the stops (Paul was in the U.S. to appear at a Capitol Records sales convention on behalf of Apple) to produce the single and its Lomax-penned B-side at EMI Studios, with himself on acoustic guitar, renowned session player Nicky Hopkins on piano, Eric Clapton on lead guitar, and Ringo on drums. Paul added his bass guitar upon his return, making it ¾ of a Beatles record. Recording begins that summer on a full Lomax album when George can spare time away from work on the White Album. Disappointingly, “Sour Milk Sea” is not a hit when it comes out in August, but George’s commitment to Lomax doesn’t waver. As soon as he finishes his work on the White Album, he makes producing Lomax’s forthcoming album his priority.

On October 16, 1968, George and his wife Pattie flew to Los Angeles, where they rented a Beverly Hills house (1330 Schuyler Road, formerly owned by Elizabeth Taylor). Lomax and loyal Beatles assistant Mal Evans shared the house with them. Time had been booked for the Lomax album at Sound Recorders Studios. George also hired the best session players in L.A. — Larry Knetchel on keyboards, Joe Osborn on bass, and Hal Blaine on drums — all part of the legendary collective known as the “Wrecking Crew,” who played on just about every major hit recorded in Los Angeles since the beginning of the decade. Lomax and Harrison handled the guitar chores. The sessions were happy ones for Harrison, who worked well with Lomax, and as producer and collaborator was afforded the respect he had been failing to get within his own band. Recording for the album, titled Is This What You Want?, ran from October 20 to November 11.

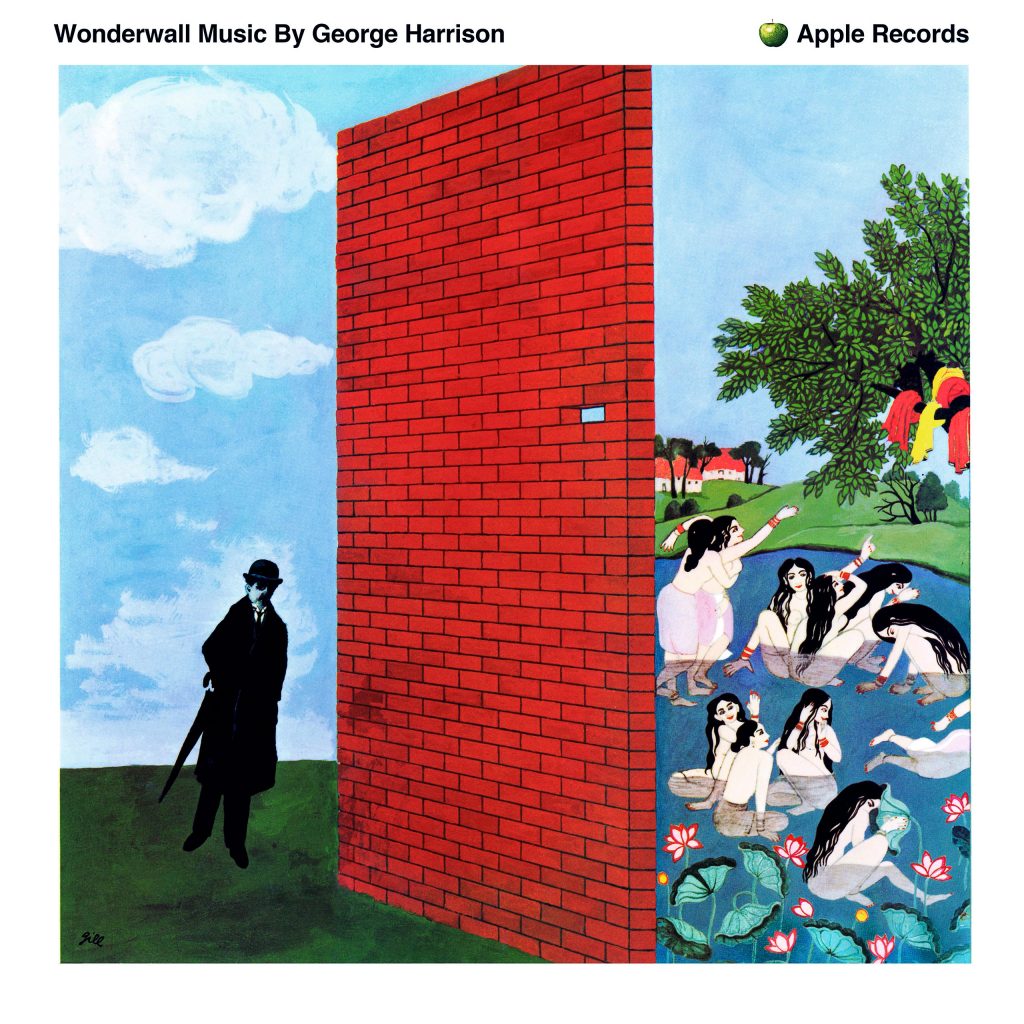

While George was busy in L.A., back in England, Apple released what most consider to be the first Beatle solo album (and the first official Apple LP) on November 1. George’s all-instrumental Wonderwall Music was the soundtrack to the Joe Massott film Wonderwall, about an eccentric British scientist’s obsession with his free-spirited hippie neighbor. At Massot’s personal request, in late ‘67 George came up with a score that was an eclectic blend of Indian ragas and swirling chunks of psychedelic rock. Although his distinctive voice is never heard, George was a hands-on arranger and composer, even traveling to EMI’s studio facilities in Mumbai to record the Indian segments back in January 1968. George subsequently recorded the rock portions at Abbey Road just before the Beatles left for their meditation retreat to India in February. He was mostly backed on this material by the Merseybeat band The Remo Four, with Clapton and Ringo performing on one track (“Ski-ing”). (The liner notes say the London portions were recorded in December 1967, but only some preliminary instrumental work seems to have been done at that time.)

As for the film itself, it got a showing at the Cannes Film Festival in May (with George & Pattie and Ringo & Maureen in attendance), but had not yet been released in Britain. As a film soundtrack album without a film, Wonderwall Music sold poorly in the U.K. When it came out a month later in the U.S., it sold quite well on the strength of Harrison’s name. Wonderwall hit British theaters in January, but never got a proper American release. It was eventually issued on a collector’s edition Blu-ray, and George’s album is now highly regarded as an early example of “world music.” (Joe Massot went on to direct Led Zeppelin’s The Song Remains the Same — most of it anyway.)

George, like all his fellow Beatles in the Sixties, had an “onward to the next thing ASAP” mentality, and didn’t seem to give the project much thought once his actual work on it was done. He did not attend the London premiere.

(The earlier soundtrack album for 1967’s The Family Way score, although officially credited to “Paul McCartney,” is usually not counted as an official solo release because Paul played no part in its performance, production, or recording, and the music itself was [ghost] co-written with George Martin.)

George attended a Capitol Records press event at the Playboy Club, where he was approached by a DJ from Pasadena’s underground FM station, KPPC, for an interview. George agreed, and on or around November 4, sat for a lengthy interview at Sound Recorders Studios that was intended to promote the White Album, but ranged over a variety of topics.

Partway through recording Is This What You Want?, the decision was made to add the Moog III synthesizer to several of the tracks, and two musicians specializing in early electronic music, Paul Beaver and Bernie Krause, were brought in to do so. Developed by Dr. Robert Moog, and (obviously) named after him, the Moog was the first commercially available synthesizer, hitting the market in 1965. Designed to electronically replicate instruments such as strings or brass, it could also generate any number of tones, noises, and ambient sounds. The Moog made a popular splash in 1968 when it was featured as the primary instrument on Wendy Carlos’ Top 10 album Switched-On Bach. In the next decade, it became one of the main components of prog-rock.

The Moog III

George was fascinated by the Moog, and in the wee hours of November 12 after the final Lomax session, he asked Krause for a demonstration of the full range of its capabilities. Krause, who also happened to be a sales representative for the incredibly expensive synthesizer, knew he had a wealthy potential customer on his hands, and happily complied. Unbeknownst to Krause, George rolled tape on the demonstration and filed it away for future use. He then whipped out his checkbook and ordered a Moog to be delivered to his home back in England. Moogs were custom-built, and George’s didn’t arrive until the following February. The bulky synthesizer was soon trucked off to EMI Studios, where it played a subtle but pervasive role on several Abbey Road songs. (The recording of Krause’s demonstration was commercially released as the side-length track “No Time or Space” on George’s “experimental” second solo album Electronic Sound in May 1969. Krause was credited with “assistance” in the liner notes and his name was originally on the back cover. A very pissed-off Krause, who had intended to use some of the sequences recorded by George for his own purposes, demanded his name be removed.)

Later on the evening of the 12th, George and Pattie paid a visit to the Chairman of the Board himself, Frank Sinatra, as he recorded his vocal tracks for his upcoming album Cycles (rush-released before the end of the year) at the United Western Recorders studio on Sunset Boulevard, just up the street from Sound Recorders. George and Pattie were two of over two dozen visitors who paraded by to pay homage to Sinatra over the course of the three-day Cycles sessions, which represented Sinatra’s attempt to blend his signature easy-listening style with songs in the folk-rock mold. George and Pattie observed the recording of “Little Green Apples,” “Gentle On My Mind,” and “By the Time I Get to Phoenix,” and when the session concluded went out to a late dinner with the legendary vocalist. (Mal Evans’ write-up of the trip in The Beatles (Monthly) Book Issue #66 has the Sinatra visit on the 13th, but most other sources say it was the 12th.)

Frank Sinatra, Pattie, and George, November 12, 1968

George skipped the L.A. premiere of Yellow Submarine, held just a few blocks from his rented home, on November 13 saying “I’ve already seen it twice.”

In no hurry to return to cold, gloomy England, George lingered in Los Angeles. He had dinner with Tom Smothers at his home on November 10, and after watching and being impressed by that evening’s broadcast of The Smothers Brothers’ Comedy Hour, he agreed to do a quick walk-on for the following week’s show. He swung by the CBS Television City complex on November 15 to tape his appearance on the subversive counter-culture favorite, which had shown the “Hey Jude/Revolution” promo film a few weeks earlier. A very young-looking George (remember, he was only 25 at the time) appeared in typical late-60s Beatles fashion (frilly shirt, boldly striped trousers), and did two-and-a-half minutes of slightly awkward comedy patter with the Smothers Brothers. The episode aired two days later.

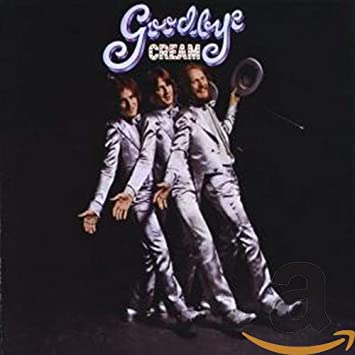

On November 21, George joined Eric Clapton’s band Cream at Wally Heider Recording Studio 3 on North Cahuenga Boulevard and added a rhythm guitar part to the song “Badge,” which he had co-written with Clapton in late summer. “Badge” would be released on the final Cream album Goodbye early the following year. (The title derived from Clapton attempting to read George’s handwritten lyric sheet, mistaking the labeling of the song’s bridge for the word “badge.”)

George’s rented Beverly Hills pad became a social hub, where frequent guests were Cass Elliott, Cream, Donovan, the Southern rock/R&B ensemble Delaney & Bonnie and Friends, and Robbie Robertson. He also made the acquaintance of (“befriended” is probably too strong a word) a few members of the Hell’s Angels motorcycle gang, who told him they were planning to visit London soon. George rather naively offered them an invitation to hang out and enjoy the amenities at Apple, never thinking the offer would be accepted.

The Band was the new big thing. Formerly Bob Dylan’s hard-rocking mid-60s touring band, the Robbie Robertson-led group toned themselves down for their debut album Music From Big Pink, released in July 1968. Big Pink’s meditative, rustic Americana music, featuring acoustic textures, subdued piano, Lowrey organ, and collective singing that would have been right at home at a campfire or revival meeting, heralded the end of psychedelia. “Roots rock” was the coming trend.

Robbie Robertson and George, New York, late November 1968

The L.A. idyll came to an end. Robertson invited George to visit him and the rest of the group at their home base in the Woodstock/West Saugerties artists’ community, located in the rural Catskill Mountains of upstate New York. Bob Dylan also had a home in the area. After a brief stop in Palm Springs, George and Pattie stayed with Dylan/Band manager Albert Grossman for several days at the end of November. George loved being around and jamming with The Band, whose loose, relaxed demeanor was so different from the tension currently surrounding the Beatles. Visits with the chronically aloof Bob Dylan were a little more stiff, but he invited George and Pattie to share Thanksgiving dinner (an unfamiliar custom for the Brits) with him and his family on November 28. (As they got to know each other over the next year, Bob and George eventually formed a very close friendship and became frequent collaborators for the rest of George’s life.)

A fuzzy snapshot of George and someone identified as David Boyle at Albert Grossman’s house. (In his autobiography, Robbie Robertson briefly referred to Boyle as a local handyman and caretaker catering to the artists and musicians who owned property in the Woodstock area)

On November 30, George literally phoned in his message for the Beatles’ annual Christmas disc from the New York City apartment of Brian Epstein’s former business associate Nat Weiss, who had handled the Beatles’ legal affairs in the U.S. during their touring years. George recorded his holiday greeting with the participation of the absolutely insufferable abomination known as Tiny Tim, whom he found briefly amusing.

On December 4, George telegrammed a panicky memo to the staff of Apple, informing (warning?) them of the imminent arrival of some Hell’s Angels. “They may look as though they are going to do you in but are very straight and do good things, so don’t fear them or uptight them.” He couldn’t have been more wrong. The Hell’s Angels visit would have uncomfortable, bordering on disastrous, results (more on this in the next entry). When he flew back to England two days later, he had a pair of brand-new songs in his pocket: “I’d Have You Anytime,” an attempt to draw Dylan out his shell, and “All Things Must Pass,” intended to be performed in the style of The Band.

George spent the bulk of December avoiding the Apple office and the Hell’s Angels (“I didn’t go because I knew there was going to be trouble,” he admitted frankly to Rolling Stone) and completing Is This What You Want?, mostly at Trident Studios, supervising overdubs of backing vocals, strings, and horns. (The Lomax album was released in March 1969, and was generally considered a flop, failing to chart despite a strong promotional push from Apple. One critic said “The response to the title is a resounding ‘no!’” Lomax left Apple in early 1970.)

He also met with a representative of the Hare Krishna religious group, Shyamasundar Das, and agreed to lend his support to establishing the Radha Krishna Temple in London. (Shyamasunder was very visibly present on the first day of the “Get Back” sessions, to the mild bemusement of John and Paul.)

Over the year-end holidays, he began an affair with French model Charlotte Martin, which was an early nail in the coffin of his marriage to Pattie.

Then George was summoned back to the world of the Beatles.

TO BE CONTINUED…

(A full source list will be provided at the end of the next entry.)