Chico on his endless tour, 1946

The Sidewalk, it was called, and then a little later, Diamonds in the Sidewalk. It was a treatment written by Ben Hecht as a project for Harpo. Like many, Hecht saw potential in Harpo as a solo star, a silent clown in the mold of Charlie Chaplin. Of course, by 1946, Chaplin was speaking on film, and Harpo was nearing sixty years old, so it may have been a little late to jump into this kind of thing.

Ben Hecht was a veteran screenwriter who had befriended the Marx Brothers in their early Hollywood days, and made many uncredited contributions to their scripts at both Paramount and MGM. In the years leading up to World War II, he was also an incredibly fervent Jewish activist to the point of radicalism, supporting the Zionist movement and even armed resistance to the British occupation of Palestine. In these endeavors, he had the moral and financial support of Harpo, with whom he had grown close. After the war, when his attention returned to his day job, Hecht took an original story outline from Harpo, and began putting together a scenario to showcase Harpo’s talents.

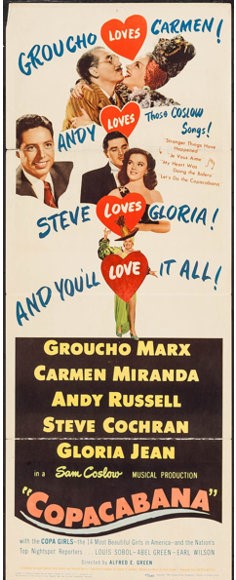

The last of the Marx Brothers’ offspring was Melinda Marx, born to Groucho and Kay on August 14, 1946, when A Night in Casablanca was still doing good business in theaters. Since its release, Groucho had earned a living with magazine articles, paid endorsements, and radio guest spots. One film offer came his way, and he jumped on it. It would be his first solo movie role, co-starring with Carmen Miranda in Copacabana.

Copacbana, 1947

After A Night in Casablanca, Harpo returned to retirement. Or semi-retirement. Every so often, he would accept an offer to perform, usually on behalf of a charity or fund-raiser for a good cause. (Sometimes the cause was helping Chico.) “Dad performed only when he had the urge,” Harpo’s son Bill said. “He’d work his ass off for a day or an evening. At the end of it, he’d say ‘I feel better. I had to get out in front of people again.’” A far cry from the terrified, non-singing Nightingale who wet himself at his stage debut in 1908.

During the war years, the ever-restless Zeppo had gradually extricated himself from the agency he ran with Gummo. He began breeding thoroughbred horses, became one of the largest citrus ranchers in the Coachella Valley, and when those weren’t enough, he established an engineering company called Marman Products, specializing in clamps and coupling devices. At its height, Marman employed several hundred workers, and supposedly produced the clamps that held the atomic bombs in place in the B-29s until they were dropped over Hiroshima and Nagasaki. (An often-repeated fact that I have been unable to confirm. So I’ll just repeat it like everyone else.)

The end of the Marx, Miller, and Marx theatrical agency seems to be shrouded in mystery. No one can agree when Gummo officially closed up shop. Robert S. Bader has the agency ending as early as October of 1947, while Simon Louivsh called it a “slow wind-up,” finally ending around 1952. Another source says it was bought outright by MCA in 1949. Whatever the case may be, Gummo continued to be his brothers’ personal agent and manager when called upon.

Chico was finally feeling his age. He walked with a distinct stoop, was often short of breath, and needed a nap in his dressing room between performances. He still delighted in pointing out a sign backstage at the Roxy Theater in New York that read “Any Girl Found On Chico Marx’s Floor Will Immediately Be Fired,” but that may have been an historical curio by 1947. In other areas, he showed no signs of slowing down. He traveled in the company of his new companion, Mary Di Vithas, known as “Mary Dee,” whom everyone agreed bore a striking resemblance to ex-wife Betty. In March of 1947, he suffered a heart attack in Las Vegas, and was sidelined for a while, but his raging gambling addiction needed to be fed, so he was soon back on the road*. He and his band performed in Germany and England later in 1947, and then toured Australia in the spring of 1948. He returned returned to Europe for a grueling five-month tour in 1949, including a four-week residency at the London Palladium as a double act with Harpo. (Harpo prepared for the gig by going to the U.K. early and doing solo shows in Leeds and Glasgow.)

Bob Hope was hosting a star-studded, one-shot radio special sponsored by Walgreens drugstore in April of 1947. The show began to run long, and guest star Groucho was getting irritated and impatient waiting for his cue. When it finally came, he ignored the script and began a long and hilarious improvisation with Hope. Listening backstage was John Guedel, producer of Art Linkletter’s game show People Are Funny (and inventor of the concept of a “re-run.”) He was struck by Groucho’s skill at ad-libbing, and realized that Groucho’s failures in radio were due primarily to sticking to the rather corny scripts that dominated radio variety in those days. Guedel approached Groucho about hosting his own radio game show, one where he could improvise freely. Groucho was dubious, but agreed to look at whatever proposal Guedel came up with.

Guedel concocted a game show where the game itself — a fairly straightforward quiz — was secondary to Groucho’s personality and interaction with the guests. He called it You Bet Your Life, and offered to go fifty-fifty with Groucho in ownership of the format. Groucho still had his doubts. “I don’t know if I can do the glad-hand bit and be sincere,” he told Guedel. He told others hosting a quiz show was “like slumming.” Still, he accepted Guedel’s offer and preparations were made, including a test recording to shop around to sponsors. Gummo handled all the financial arrangements.

Groucho’s first solo film, Copacabana, was released in May of 1947. “Solo” in the sense of without his brothers, he still had to contend with the hyperactive presence of Carmen Miranda, the Brazilian singer famous for wearing fruit on her head. Groucho played her shady agent in his usual style. He still sported a fake mustache, only instead of a swipe of greasepaint, it was a proper paste-on job. Copacabana was a fairly solid musical comedy that was more of a showcase for Miranda, and got decent reviews at the time, but it was far from a classic. “The only reason I took the job is because it was the only one offered to me,” said Groucho. “Except for making a Marx Brothers picture, something I have no more desire for or interest in.” United Artists saw potential in Marx-Miranda as a comedy team for future films, but Groucho demurred. Movies were clearly not going to be a major part of his career going forward, so it’s a good thing the You Bet Your Life deal had come along.

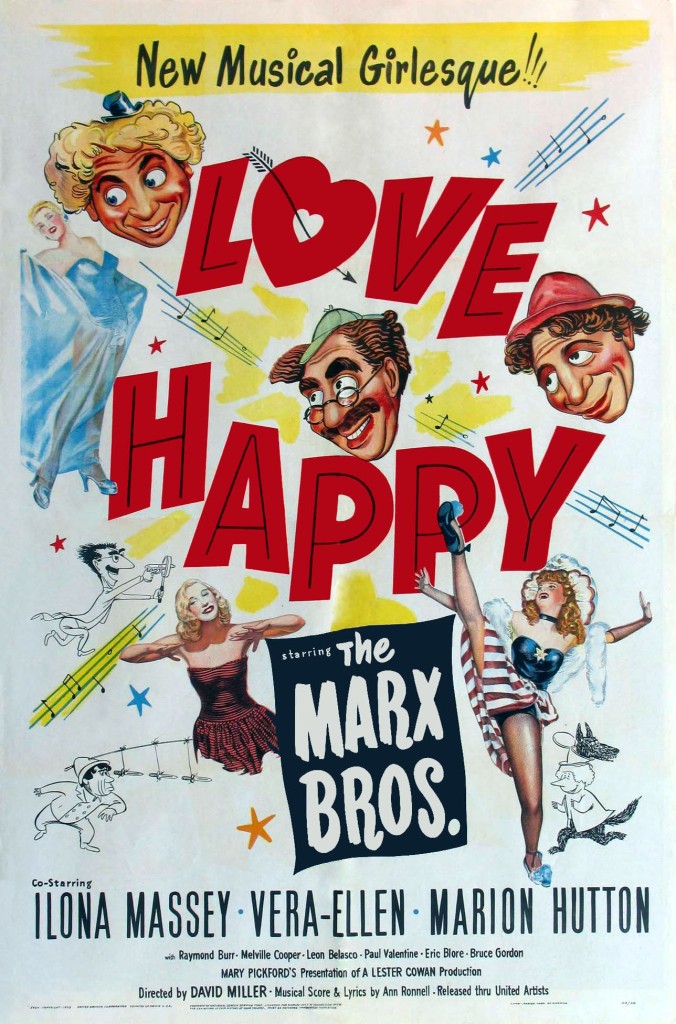

In the meantime, Ben Hecht’s treatment for Harpo, Diamonds in the Sidewalk, was crawling its way towards becoming a reality. Hecht, who was very in demand, wrote a rough screenplay, then opted out of further participation. Subsequent rounds of the of screenplay went through a rogue’s gallety of writers, with two (Frank Tashlin and Mac Benoff) ending up with the credit. Early on, Chico was added to the story in a supporting role. By the time You Bet Your Life was about to hit airwaves, Groucho had grudgingly agreed to a small cameo appearance. Adding the other Brothers was at the insistence of producer Lester Cowan. “It was never designed as a Marx Brothers film,” insisted director David Miller. Nevertheless, before the project even left the early screenplay phase, all three brothers were on board.

Early days of You Bet Your Life, ABC, Fall 1947

You Bet Your Life premiered on the smallest of the three radio networks, ABC, on October 27, 1947 to the smallest of audiences (it was ranked 96th in the weekly ratings). But they tinkered with the format, added the “secret word” that could gain contestants bonus cash, and hired a straight-laced announcer named George Fenneman that Groucho could play off of like a “male Margaret Dumont.”

Radio shows could now be pre-taped, so each episode of You Bet Your Life, which sometimes rambled on for almost ninety minutes in the studio, could be edited down to a tight 24 minutes containing only the best bits. Although Guedel’s initial interest in Groucho had been due to his ad-libbing skills, You Bet Your Life could be said to be semi-improvised at best. The contestants were pre-interviewed extensively, and Groucho was given an array of witty remarks by his writers based on the contestants’ responses and personalities. (Of course, he could always choose to go rogue as the tape rolled, which he often did.)

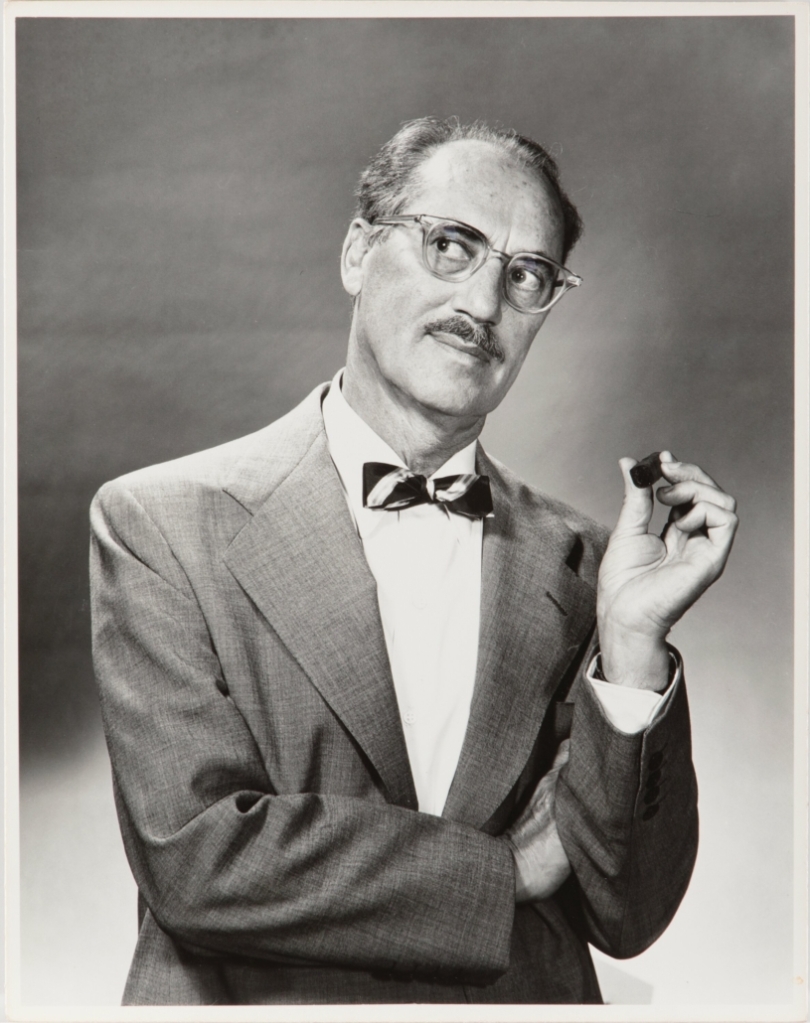

Groucho humbly accepted most of the much-younger Guedel’s suggestions and advice. “All your shows have been successful,” he told Guedel. “I’ve lost every sponsor I’ve ever had.” Groucho drew one line in the sand — he refused to put on the old frock coat and greasepaint mustache for the studio audience. “That character is dead,” he insisted. Instead, he grew a real mustache (later augmented with a thin, subtle toupee that hardly seemed worth the effort of putting on).

You Bet Your Life’s listening audience grew slowly but steadily. When their contract with ABC expired in 1949, Marx and Guedel were offered a small fortune to jump to CBS, where the show entered the top ten and stayed there for years.

The Marx Brothers, 1948

Diamonds in the Sidewalk was re-titled Love Happy, and Mary Pickford, the former silent film star and one of the founders of United Artists, joined Lester Cowan as producer. Groucho’s cameo appearance had grown into a full supporting part in the most recent draft of the script. His old greasepaint mustache character was indeed gone, replaced by the much more normal-looking character of Sam Grunion, private eye. Grunion was intended to be a framing device, appearing only at the beginning and end of the picture as he talked to the camera, introducing and wrapping up the Harpo storyline.

The main story features Harpo as a loveable tramp who provides stolen food to a poor, struggling song-and-dance troupe (featuring Chico as “Professor Faustino”). Little does he know that one of the cans of sardines he pilfers contains a stash of smuggled diamonds, and the smugglers want them back.

Sam Grunion, Private Eye

Love Happy started shooting in August of 1948 with David Miller at the helm, and Harpo with the bulk of the screen time. Harpo soon found he did not get along with the abrasive Cowan, which led to a tense atmosphere on set. Cowan ran the production on a shoestring, and had to completely shut it down at least once due to lack of funds. Cowan’s solution was to re-tool the chase sequence at the end to be set among the city rooftops, and literally sold the billboards seen in the background to companies for in-movie advertising.

As if to atone for “slumming” on a quiz show, Groucho was also working on something on a somewhat higher artistic plane. He put the finishing touches on the play he had been writing, off and on, with Norman Krasna for several years, and declared it ready for production. The problem was, no one who read it liked it all that much. Time For Elizabeth lacked Groucho’s trademark bite. It was a mild-mannered domestic comedy about a man who takes an early retirement to Florida, only to find retirement doesn’t agree with him. The leading role was intended to be played by Groucho himself, but his commitment to You Bet Your Life ruled out that option. Groucho and Krasna put up their own money, and Krasna would direct. Otto Kruger was cast in the lead, and Time For Elizabeth opened at the Fulton Theater on Broadway on September 27, 1948. It managed eight performances before closing in the face of reviews that ranged from dismissive to scathing.

The cast of “It’s Only Money,” as it was called in 1948

Groucho did not have time to brood over the play’s failure. In addition to recording his quiz show, he filmed his scenes for Love Happy, and as soon as those were done, headed over to RKO Studios through the end of the year to co-star in a comedy with Jane Russell and Frank Sinatra called It’s Only Money. RKO had just been purchased by Howard Hughes, and once completed, It’s Only Money gathered dust on the shelf while Hughes spent the next few years reorganizing the company in his usual obsessive but disordered manner.

One of the only times in Love Happy when Groucho is onscreen with another Brother

Over at General Service Studio, the unpleasant experience of filming Love Happy finally came to an end for Harpo and Chico in January 1949, with two days of reshoots in February. The film sat in limbo while Lester Cowan scraped together enough funds to complete post-production work. He decided Groucho should appear throughout the film, so bits and pieces of the Sam Grunion framing device were cut out and edited into random places throughout the story. Groucho also provides narration due to the film’s total lack of coherence at times.

Love Happy went into extremely limited release in October 1949, then it was pulled by United Artists for more editing. It received its nationwide release on March 3, 1950. Unlike A Night in Casablanca, it was not a late-period success. Audiences ignored it and critics panned it. Neither Harpo nor Groucho mentioned it in their memoirs. Everyone wanted to forget its existence. Executive producer Mary Pickford did forget its existence. (When asked about the film years later, her response was “Love what?”) By coincidence or not, it was the last film she ever produced. The only thing that could be said for it was that Marilyn Monroe appeared as one of Grunion’s prospective clients at the end of the movie. It was her third film. She had two lines.

Is Love Happy a true Marx Brothers movie? I vote No. It was conceived and planned by Harpo and Hecht as a solo turn for Harpo. It was only billed as “the Marx Brothers” because Cowan broke the contractual agreement that forbade him from doing so. Chico is tacked on. Groucho is a tack-on to a tack-on. Groucho isn’t even really “Groucho” anymore, although his old caricature is used in the film’s publicity material.

And all three Marx Brothers never share a single scene together. I will die on the hill of there being only twelve Marx Brothers movies. But…it’s listed in all the Marx Brothers movie books alongside the others. So I’ll express my disdain for it by calling it even less watchable than Room Service.

The Holy Bee’s Ranked List of Marx Brothers Movies

- Duck Soup

- Animal Crackers

- Horse Feathers

- A Night at the Opera

- Monkey Business

- The Cocoanuts

- A Day at the Races

- A Night in Casablanca (I actually consider this as a tie with Races)

- Go West

- At the Circus

- The Big Store

- Room Service

- Love Happy (if it must be counted)

Chico finally called a halt to his seemingly endless touring in late 1949. The physical grind was just too much. If movies weren’t really an option, and live performances close to home (no further than Vegas, please) were sporadic, how could he earn the salary that he would promptly lose?

At the turn of the decade, there was a new entertainment landscape…television!

Chico had an old-school performer’s disdain for television, and said that it “ruined comedy.” But performing on television was just the sort of soft racket that could keep the money flowing in. He was the first Marx Brother to appear on TV, playing piano on an episode of Texaco Star Theater in October of 1948. After a few other (now lost) appearances on different shows, he eagerly accepted a main role on an early musical sitcom, The College Bowl, playing the proprietor of a soda fountain where all the college kids hung out (and frequently sang). Chico dispensed ice cream sodas and fatherly advice to the clean-cut youngsters, still with his Italian accent. (One of the college boys was Andy Williams). It only lasted one season (1950-51), but Chico didn’t mind too much. Early television was hungry for content, and there seemed to be no shortage of options for cashing in on his famous name and keeping his bookies happy.

Groucho also recognized TV as the wave of the future. He had spent only one season with CBS before moving to NBC, because they offered him a television version of You Bet Your Life in addition to its original radio format. You Bet Your Life made its TV debut on October 4, 1950, and it ran for eleven years.

George Fenneman and Groucho, early 1950s

Unlike Chico, Harpo loved television, but his initial interest was limited to watching it. He had it on all the time, but his wife Susan said anything besides comedy put him to sleep. His performing bug was starting to bite again, though. He undertook a short national tour in the fall of 1950, and made his TV debut on The Colgate Comedy Hour on November 11, 1951. As the 1950s went on, Harpo was lured out of semi-retirement more and more to perform on various TV shows, often teaming with Chico.

Harpo and his three youngest children

Groucho’s second marriage was unraveling faster than his first marriage had. He simply had few viable instincts at being a long-term domestic partner. Once he was married, it seemed he could barely stand to be in the same room with his wife. Both Ruth and Kay were prone to low self-esteem (medicated by drinking, a condition both of them strugggled with before Groucho), which was made much worse by his indifference to their needs. But indifference was better than the caustic put-downs, his frequent form of interaction with those closest to him. His children were spared this side of him when they were young (he was great with little kids), but as they grew to adulthood, they became targets of his churlishness as well. He got along well with his brothers, because they didn’t give a damn what he said and their feelings couldn’t be hurt. It was just Groucho being Groucho. Why couldn’t everyone handle it that way? Groucho must have wondered as Kay packed her bags. The divorce was finalized in May of 1951. After living with Kay for a while, Groucho took custody of six-year-old Melinda due to Kay’s worsening alcoholism (euphemistically referred to as her “illness” in court documents). Everyone (even those hurt by him) agreed Groucho was a fundamentally decent man who had an immensely difficult time communicating beyond his emotional barrier of jokes and sarcasm, rarely revealing the sensitivity everyone knew was there. He certainly would never consider therapy, especially in that day and age, but one imagines it could have done wonders for him.

Groucho walks Melinda to school, early 1950s

Three years after it was filmed, Howard Hughes finally allowed It’s Only Money to escape from his clutches in December of 1951. It was re-titled Double Dynamite. I don’t know whether to be proud of or embarrassed by the fact that it did not occur to me that the title was a reference to Jane Russell’s top-heavy figure until I read that it was. By the time it came out, Groucho had already finished another leading role. A Girl in Every Port was a lame Navy buddy comedy featuring Groucho and William Bendix as a couple of (very) over-the-hill sailors who get mixed up with gangsters and horse racing. Like Double Dynamite, when A Girl in Every Port was released in January of 1952, it sank like a torpedoed ship. With a few exceptions, these two films marked the end of Groucho’s movie career. Who needed it? America loved You Bet Your Life. (Both Dynamite and Port were produced by Irwin Allen, more on him later.)

Harpo became so enamored of performing on TV, he signed a contract with NBC starting in 1952 to do a number of guest appearances. Pretty soon, he was popping up on The Colgate Comedy Hour, U.S. Royal Showcase, The RCA-Victor Show, and The All-Star Revue. (As in radio, many TV variety and game shows until the mid-1960s were named for their single sponsors. The very first sponsor of Your Bet Your Life manufactured make-up compacts, and pulled their sponsorship early when every single compact they put on the store shelves sold out. Why advertise for an unavailable product?)

The March 30, 1952 episode of The Colgate Comedy Hour featured Harpo and Chico doing the act they had worked up for the London Palladium shows. Soon this two-man version of the Marx Brothers was appearing frequently in the clubs and hotel lounges of Las Vegas. Harpo also did another turn as the Property Man in The Yellow Jacket for the Pasadena Playhouse. So much for his retirement. (And “Harpo” appeared on I’ve Got A Secret in 1954 — the secret being it was really Chico dressed in Harpo’s trademark costume.)

Groucho at the height of his TV popularity, mid-1950s

The non-performing Brothers, Gummo and Zeppo, abandoned Beverly Hills for Palm Springs in the mid-1950s. Despite his renewed interest in performing, Harpo’s TV schedule was not exactly onerous, and by 1957 he had decided to join the Palm Springs contingent. He moved his family and their gaggle of pets to a new, custom-built compound (designed by famous architect Wallace Neff) that he dubbed “El Rancho Harpo.” The house overlooked the fourteenth hole of the Tamarisk Country Club, which was their social hub. (All of the Brothers except Chico are on the list of the club’s 65 original founders.) Even Groucho bought a condo nearby.

Gummo spent his days reading the paper, checking up on his investments, and taking long lunches at Tamarisk. “Dad was not a super-energetic guy,” Gummo’s son Bob remarked. (Bob was a producer on the TV version of You Bet Your Life.) Zeppo got divorced in May of 1954, and also sold off Marman Products to the Aeroquip Corporation for a substantial amount. Zeppo’s retirement was a leisurely blur of golf, card games, and cocktail parties, underwritten by the profits of his company sale. He held on to his massive grapefruit orchard, which all the Brothers had a stake in and agreed was the most consistent, if least glamorous, money-maker in their lives. (By the way, if you plan to visit Palm Springs, El Rancho Harpo is now available as a luxury vacation rental, and God, do I want to spend a summer there.)

As Zeppo’s marriage ended, Groucho decided the third time was the charm. While shooting A Girl in Every Port, Groucho met Howard Hawks’ new fiancee, Dee Hartford, a fashion model who was playing a small role in the film. She introduced him to her single sister, Eden, and they hit it off. Groucho married 24-year-old Eden Hartford while vacationing in Sun Valley, Idaho, on July 17, 1954. He had a new house (also based on a Wallace Neff design) built for them in the Trousdale Estates, the classy new development in the winding streets that overlooked the Beverly Hills flats. They settled in…and Groucho’s pattern of behavior when confronted with married life began again.

Like Harpo, Groucho made frequent guest appearances on a number of shows, and both Brothers discovered the easy work and big money of commercial endorsements. Harpo’s TV work reached its pinnacle with his appearance on the most popular comedy in the country, I Love Lucy, on May 9, 1955. He and Lucille Ball recreated the mirror routine from Duck Soup, a performance that was seen by multiple generations when I Love Lucy went into syndication and began its endless pattern of re-runs. It was many kids’ first exposure to anything Marxian.

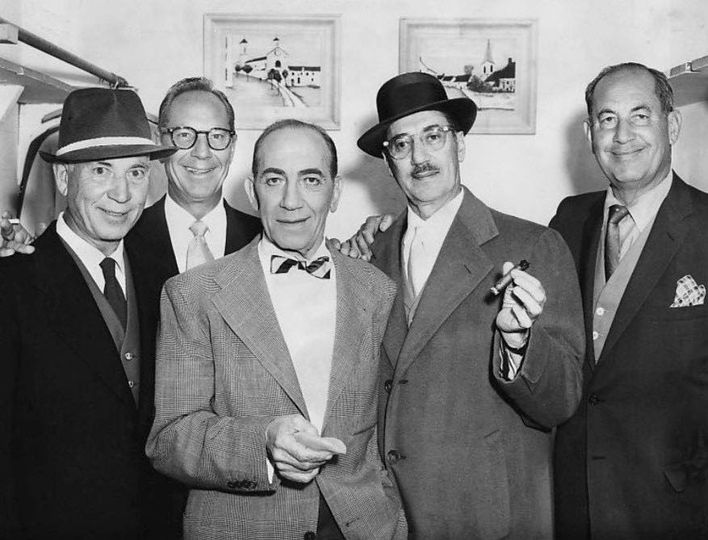

In August 1956, Chico was cast in a touring revival of The Fifth Season, once a pretty well-regarded Broadway comedy about the “rag trade,” now almost totally forgotten (and not to be confused with the immensely popular recent fantasy novel, which, believe me, dominates Google searches of that title). What few details of the plot I could dig up indicate the story concerns two partners in a failing clothing business who decide sex sells, and bring in a bevy of gorgeous models to attract buyers. One presumes complications and hilarity ensue. Chico played the senior partner…and for the first time in his performing career dropped the Italian accent and used his natural New York voice. The closing run of performances in Los Angeles had all of the Brothers in attendance at one point or another, and was considered enough of an event to be featured on the talk show Tonight: America After Dark on February 18, 1957. The episode marks the only occasion when all five Marx Brothers appeared together on TV.

The five Marx Brothers, February 1957. Chico is in stage make-up for his role in The Fifth Season

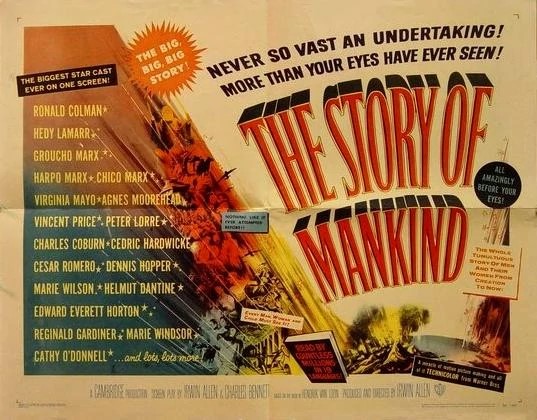

Long before he was known as the “Master of Disaster” for producing 1970s films like The Poseidon Adventure and The Towering Inferno, Irwin Allen was a humble staff producer for RKO who had ambitions to break into directing. After leaving RKO and doing a few documentaries, Warner Brothers gave him the go-ahead to direct his first narrative film.

Allen decided he would go big — The Story of Mankind, loosely adapted from the non-fiction children’s book of the same name. Allen wanted his film to be everything at once. It would be epic! It would be educational! It would be funny and dramatic! It would have an all-star cast! It would be filmed over two years in 18 countries, advised by a panel of expert theologians and historians! He even came up with an unintentionally hilarious framing device where all of humanity is put on trial in the “Great Court of Outer Space,” and is prosecuted by the devil (“Mr. Scratch,” played by Vincent Price) and defended by the “Spirit of Man” (Ronald Colman), whatever that is.

Warner Brothers then gave him a budget that would allow exactly none of this to be pulled off successfully.

Allen had to rely on a bunch of stock footage, and calling in favors from his B-list celebrity acquaintances. Hedy Lamarr, Peter Lorre, John Carradine, Cesar Romero, and several others (including young Dennis Hopper as Napoleon) all heeded the call to play an important historical figure in a self-contained segment. Allen would have each of them for one day of shooting on cheap, tiny sets, and paid them $2000 each. He got Groucho to play Peter Minuit, who according to legend swindled the Native Americans out of Manhattan Island in 1626. Harpo played a silent Isaac Newton, who was evidently a harpist as well as a physicist, getting bonked on the head with apples. Chico was an Italian monk being convinced the world was round in the Christopher Columbus sequence. None of them appeared together. But at least they were in Technicolor.

When The Story of Mankind was released on November 8, 1957, it was laughed out of theaters (by those few who chose to go see it), and is now widely regarded as one of the worst films of all time. Allen’s first “disaster” was unintended, but he was not deterred, learned from his mistakes, and what little there was of his future directorial work was definitely a higher grade of cheese (The Lost World, Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea).

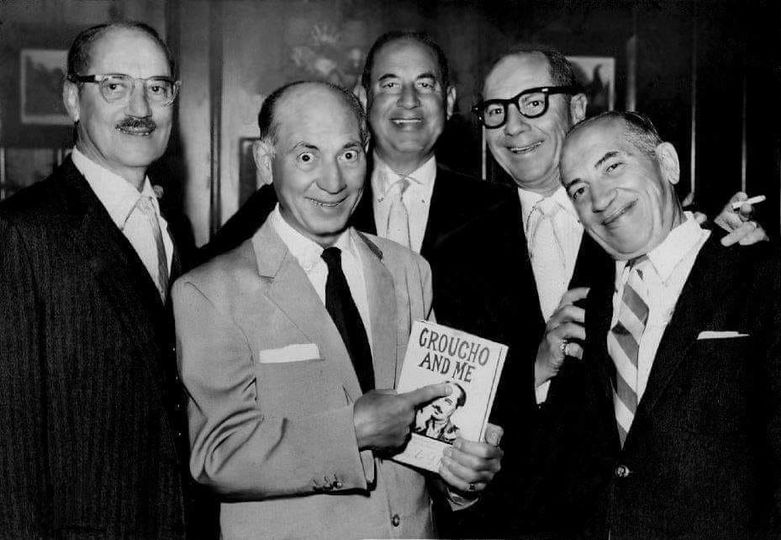

Groucho decided there was still some hope for his play Time For Elizabeth. He and Eden toured with it in summer stock in 1957, 1958, 1959, and 1963. He finally got to play the lead, and re-wrote the dialogue to contain more barbed, Groucho-esque wisecracks. The play took on new life, and everyone who saw it in its later incarnations agreed it was a pleasant evening out, if not much more. He also published his autobiography in 1959.

The Brothers lend a hand to promote Groucho’s autobiography, 1959

Not long after the IRS dunned him for almost $78,000 in unpaid income tax, Chico finally acquired a divorce from Betty. Five days later, he married Mary Dee, his companion since 1942, on August 22, 1958. Sources say it was actually Betty who demanded the divorce so she could re-marry, and that Chico would have happily kept Mary Dee in the “girlfriend zone” perpetually, but since the divorce was now a fait accompli, he might as well marry her. Zeppo also re-married, in 1959, to former showgirl Barbara Blakeley.

The Incredible Jewel Robbery, 1959

Chico joined Harpo in silent pantomime for CBS’s General Electric Theater episode “The Incredible Jewel Robbery.” The thirty-minute piece was intended to be a throwback to old two-reel silent comedies, and aired on March 8, 1959. Marx biographer Simon Louvish describes it as “beyond sad.” At this point, Harpo and Chico’s deeply-lined faces look downright disturbing peeking feebly from under their curly comedy wigs (wigs don’t wither away from arteriosclerosis). The only thing incredible about it is how loud the obtrusive canned laugh track is. The episode surely would have been completely forgotten had not Groucho popped up in the last few seconds, marking the final time the three performing Marx Brothers appeared on a screen for public consumption.

The last appearance of the Marx Brothers together. The effect is somewhat spoiled by the random guy in the back, playing a member of a police line-up

There was one more attempt later that year to round up the Marx Brothers for a TV project. Producer Phil Rapp came up with an idea to pair Chico and Harpo as a pair of guardian angels lending a hand to the people of earth in a fantasy sitcom called Deputy Seraph. Groucho would do a short bit as their heavenly boss every third episode. They filmed some test footage, but it wasn’t to be. Chico’s rapidly worsening health meant that no insurance company would cover the production.

The Marx Brothers were done.

Chico’s final TV appearance was on a show called Championship Bridge, in which the presumably bored-to-tears audience watched people play an incredibly dull, slow-moving card game. World Series of Poker this ain’t. What would have been relegated to deep cable or an internet stream in a later era (if anyone bothered to show it at all) was happily broadcast by ABC on October 16, 1960. (Chico lost, by the way.)

Chico spent almost as much time in the hospital as he did at home through 1961. He died on October 11, 1961, of the heart problems that had plagued him for twenty years. Groucho remained stoic through the memorial service, insisting that he wasn’t sad. “Chico had more fun out of life than the rest of us combined.” But son Arthur Marx recalled that at the dinner after the service, his teetotaling father downed several straight whiskeys and had to be helped to the car, indicating his inner devastation.

1887 – 1961

Health-wise, Harpo seemed to be following in Chico’s footsteps, suffering from fatigue and chest pains, and having a series of mild heart attacks in the late 1950s. His doctors ordered him to slow down a bit, and appearances became less frequent. He still made several more TV appearances in the early 1960s, most memorably as a (very creepy-looking) silent mime performing in a department store window who witnesses a murder in “A Silent Panic,” an episode of the anthology series The DuPont Show with June Allyson, which aired in December of 1960. He published an epic 650-page autobiography in 1961, Harpo Speaks! (as told to writer Rowland Baber — Harpo still wasn’t much for putting pen to paper). He fudges more than a few facts (including making himself five years younger) and makes up a few anecdotes out of whole cloth, but it was — and remains — a great read, “but don’t set your clocks by it” as Susan Marx warned in her own memoirs.

He announced his true, actual, no-kidding retirement in early 1963, and this time stuck to his word. Harpo was seen no more beyond El Rancho Harpo and the Tamarisk Country Club, except for a few speaking (!) engagements on behalf of the United Jewish Appeal (and a short trip to Israel). Heart-bypass surgery was in its infancy, but after consulting with his family, he decided to take the chance. The surgery proved too much for the frail Harpo, who died two days after the procedure on his 28th wedding anniversary, September 28, 1964. No word on if Groucho drowned his sorrows in whiskey this time, but Arthur reported it was the first and only time he saw his father cry. Harpo’s ashes were allegedly mixed into the seventh hole bunker of the Tamarisk golf course.

1888 – 1964

Groucho continued to live his life as a professional celebrity. You Bet Your Life left the airwaves in 1961 (the radio version a year earlier), but he never left the public eye. He fulfilled a lifelong dream by appearing as Ko-Ko in Gilbert & Sullivan’s The Mikado for NBC’s Bell Telephone Hour in 1960. He was the guest host for The Tonight Show during the big transition between Jack Parr and Johnny Carson in the fall of 1962. A truncated version of Time For Elizabeth was televised on The Chrysler Theater in 1964.

One more Time For Elizabeth, Groucho & Eden, 1964

On April 17, 1965, The Hollywood Palace broadcast an episode featuring Groucho and Margaret Dumont re-creating the opening scene of Animal Crackers. Dumont had died the month before, a few days after the part was taped.

Groucho and Margaret Dumont, one last time, 1965. Supposedly, he took one look at his toupee in this footage and retired it in favor of berets and tam o’shanters (except for Skidoo, see below)

Not everything was a colossal success. Two TV shows, Tell It To Groucho (CBS, 1962) and Groucho (for Britain’s ITV, 1965) lasted only a few episodes. He put on a jet-black toupee and darkened his mustache with a dab of the old greasepaint to play a crime boss named “God” in 1968’s Skidoo, a surreal attempt by director Otto Preminger to tap into the counterculture that joins The Story of Mankind on the list of worst movies ever made. It’s everything you’d expect from a movie made by clueless, middle-aged-bordering-on-elderly white men addressing “hippies” and “acid” and “free love,” and starring Jackie Gleason, Carol Channing, and Mickey Rooney. I watched it on YouTube at about two in the morning, and wondered if I had fallen asleep and tumbled into a fever dream.

Groucho in Skidoo, the less said about which the better

Eden divorced him in 1969 for the usual reasons. The sad tale of his final years with manager/companion Erin Fleming is best told in Steve Stoliar’s book Raised Eyebrows: My Years Inside Groucho’s House. Stoliar worked as an assistant to Groucho, sorting through his personal papers and memorabilia, and had a front-row seat to the drama that clouded Groucho’s twilight era. That Erin Fleming was mentally unstable is putting it mildly (she later declined into full-blown paranoid schizophrenia), but Groucho’s friends and family were divided as to her impact at the time. A minority of them (including Zeppo) said her attention to him and her efforts to keep him performing gave him inspiration and added years to his life. But most others said she saw him only as a meal ticket, and her treatment was exploitative and drifted into downright elder abuse as he grew weaker.

At Fleming’s prompting, and after a few small warm-up gigs, he did a one-man show at Carnegie Hall on May 6, 1972. Even for one night only, no one was sure if he could pull it off. He did, barely, and the resulting record album, An Evening with Groucho, became a best-seller for A&M Records.

Then the strokes started coming. A minor one in 1971 was followed by a major one in September of 1972 that forever altered his speech. No longer would we hear that nasal, fast-talking patter. Groucho now spoke in a quiet, slurred drawl. He could still be quite funny — he remained an early-70s talk show staple — but it wasn’t the same. Relatively small strokes would plague him for the rest of his life, and after each one, he faded a little bit more.

He received an honorary Oscar in April of 1974, “in recognition of his brilliant creativity and for the unequaled achievements of the Marx Brothers in the art of motion picture comedy.” He was a presenter at the 1975 Emmys, where he was practically stepped on by drunken co-presenter Lucille Ball. Finally, they propped him up for a very short, semi-coherent spot in one of the more god-awful pre-taped Bob Hope specials in 1976 which, when I saw it, made me hate that sideways-grinning jackass Bob Hope even more than before.

The surviving Brothers, October 1975

He was increasingly deaf and drifting in and out of dementia, so he was not told of Gummo’s death in April of 1977.

Groucho died of pneumonia at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center on August 19, 1977. Elvis Presley’s death three days before was still dominating the headlines. The litigation over his estate continued for years.

1890 – 1977

Zeppo was divorced from Barbara in 1973 (she went on to marry Frank Sinatra). The profits from the sales of his sold-off investments eventually ran out, and in the 1970s he was living on a weekly allowance provided by Groucho. Except for the occasional lawsuit (he remained something of a scrapper), he lived a quiet life alone. He died of lung cancer on November 30, 1979.

There are some aspects of being human that are as lasting as the stars. And none are more lasting than the stars of bedlam. — Joe Adamson

* A note on Chico’s 1947 heart attack. Many sources say he faked it to get out of doing a gig he didn’t want to do. Others say it was the real deal, and the fake heart attack was a few years earlier. (No one disputes the fact that he once faked a heart attack.)

SOURCES FOR PARTS 1 – 11:

Adamson, Joe — Groucho, Harpo, Chico and Sometimes Zeppo: A Celebration of the Marx Brothers

Arce, Hector — Groucho

Bader, Robert S. — Four of the Three Musketeers: The Marx Brothers on Stage

Bader, Robert S. — The Marx Brothers TV Collection DVD booklet

Coniam, Matthew — The Annotated Marx Brothers: A Filmgoer’s Guide to In Jokes, Obscure References and Sly Details

Coniam, Matthew — That’s Me, Groucho!: The Solo Career of Groucho Marx

Diamond, Noah — Gimme A Thrill: The Story of I’ll Say She Is – The Lost Marx Brothers Musical and How It Was Found

Eyles, Alan — The Complete Films of the Marx Brothers

Kanfer, Stefan — Groucho: The Life and Times of Julius Henry Marx

Keaton, Buster with Charles Samuels — My Wonderful World of Slapstick

Louvish, Simon — Monkey Business: The Lives and Legends of the Marx Brothers

Marx, Groucho — Groucho and Me

Marx, Groucho with Richard J. Anoible — The Marx Brothers Scrapbook

Marx, Groucho with Hector Arce — The Groucho Phile: An Illustrated Life

Marx, Harpo with Rowland Barber — Harpo Speaks!

Marx, Maxine — Growing Up with Chico

Marx, Susan Fleming with Robert S. Bader — Speaking of Harpo (a few minor additions and corrections were made to some posts after the publication of this memoir in July 2022)

Mitchell, Glenn — The Marx Brothers Encyclopedia

Monod, David — Vaudeville and the Making of Modern Entertainment, 1890-1925

Stoliar, Steve — Raised Eyebrows: My Years Inside Groucho’s House

Zimmerman, Paul D. and Burt Goldblatt — The Marx Brothers at the Movies

https://www.concordtheatricals.com/p/9192/the-fifth-season

https://worldcinemaparadise.com/

The Marx Brothers Council podcast

Thank you for a wonderful series! I remember first seeing Groucho on late night back in the 70s when I was in HS. He cracked me up as a young 15-16 year old. I grabbed the TV guide (remember those) and if I recall correctly, duck soup was on later that same night, or more like early morning. I stayed up, and fell in love with the Marx Brothers. Thanks again. I’d say “thanks for the memories” but won’t, based on your earlier comment.

Glad you enjoyed it!

Very enjoyable read. Thanks!

I have spent the last days reading this series, I couldn’t stop till I finished. Really amazing, thanks for the effort of putting it together.

Greetings from Spain, Jorge García.

Thanks for reading!