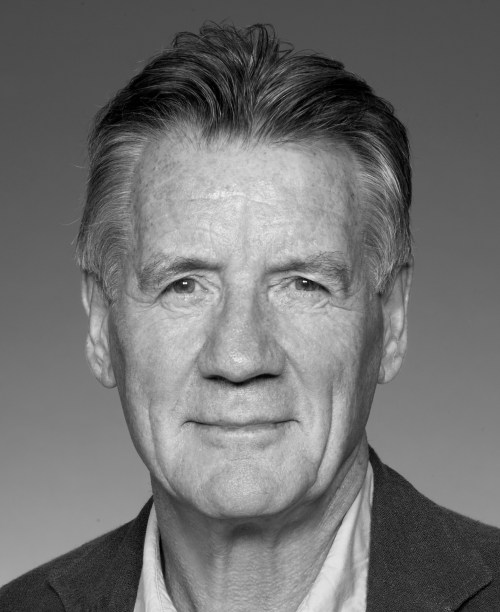

Although ERIC IDLE was actually the second-youngest Python (Palin has the distinction of being the youngest by only a few weeks), of all the Pythons he’s the one who projected an aura of youthful rebellion. Cleese, only four years older by the calendar but light-years away in demeanor, might as well have been his father. He had rock-idol hair past his shoulders during the Python years, and even though it was mostly kept pinned under the wigs of his characters onscreen, the viewer sensed a certain anti-authority wickedness in his eyes.

Although ERIC IDLE was actually the second-youngest Python (Palin has the distinction of being the youngest by only a few weeks), of all the Pythons he’s the one who projected an aura of youthful rebellion. Cleese, only four years older by the calendar but light-years away in demeanor, might as well have been his father. He had rock-idol hair past his shoulders during the Python years, and even though it was mostly kept pinned under the wigs of his characters onscreen, the viewer sensed a certain anti-authority wickedness in his eyes.

Idle had none of the fuzzy, free-spirited anarchism of Jones & Gilliam, nor the warmth of Palin. You got the sense you didn’t want to piss him off. His writing and performances were more sharp-edged, and he quickly garnered the title “The Sixth Nicest Python.” With the Cleese/Chapman and Jones/Palin writing partnerships established early within the group (and Gilliam off doing his animations), Idle wrote solo. He didn’t mind, he said, but it did make it twice as hard to get his stuff in the show because he didn’t have a partner acting as a sympathetic laugh-track during group read-throughs.

As the group branched into other media, Idle began building a niche as the “musical” Python — he was a decent guitarist and had a knack for catchy, witty lyrics. Many of the more memorable Python songs came from him, including Life of Brian’s mighty “Always Look On the Bright Side of Life,” which has practically replaced “God Save the Queen” as the British national anthem. (Idle’s collaborator on some of the melodies was composer and arranger John DuPrez, who scored Brian and The Meaning of Life, and provided the music for Idle’s Spamalot, see below.)

Idle, like Cleese, has raised some eyebrows (my own included) for seeming to be non-discriminating with many of the projects he’s chosen over the last 25 years or so, leading to accusations of money-grubbing. Idle himself has sometimes played on this, naming his two concert tours the “Eric Idle Exploits Monty Python Tour” and the “Greedy Bastard Tour.”

However, on his highly interesting website (well, highly interesting to me — it’s mostly his “reading diary”), he points out that the majority of his recent projects have been taken on with no expectation of profit, and if you really break down his choices, a lot of his more dubious stuff was something that may have seemed genuinely interesting at the time, or was done as a favor to a friend. So let’s give him the benefit of the doubt.

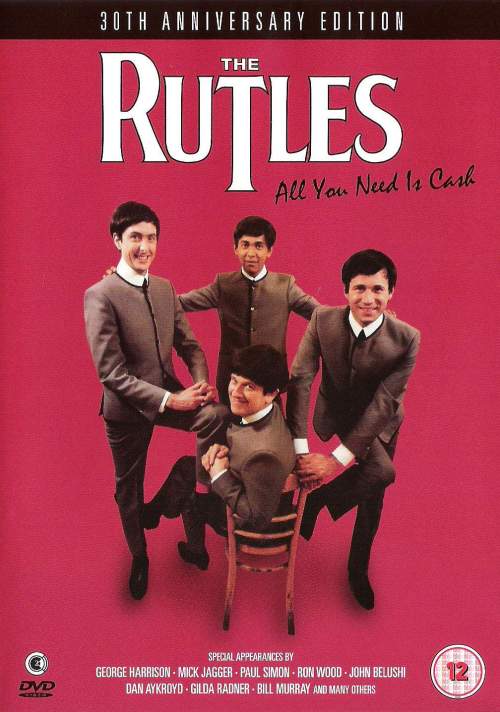

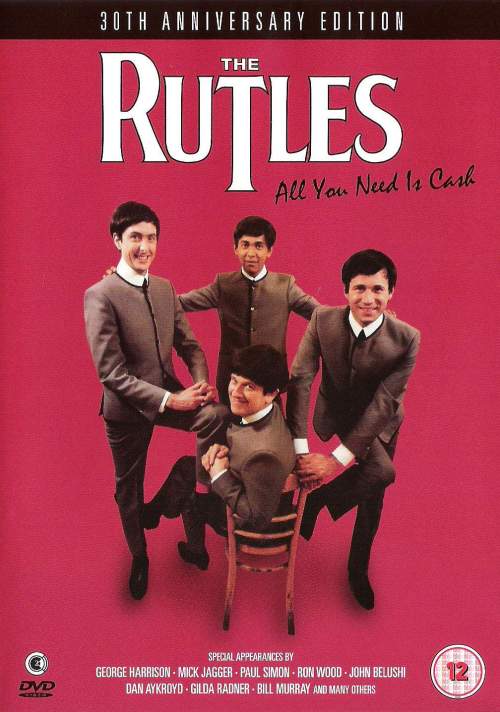

BEST PROJECT: The Rutles — All You Need Is Cash

BEST PROJECT: The Rutles — All You Need Is Cash

TV movie, first broadcast on NBC, March 22, 1978.

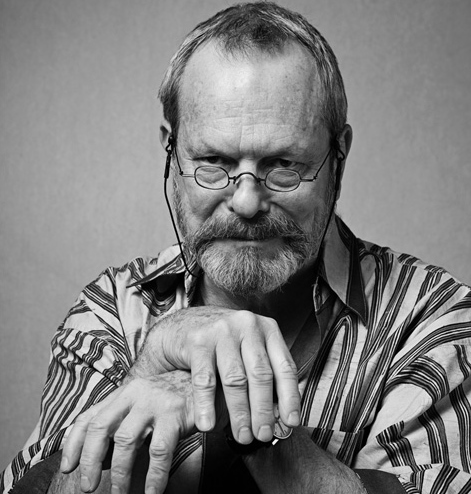

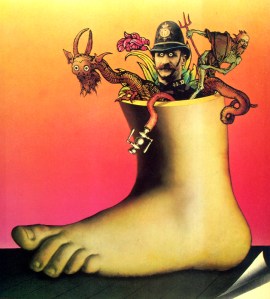

Rutland Weekend Television was part of the first wave of Python solo projects, coming to BBC screens in 1975, around the same time as Cleese’s Fawlty Towers and the pilot episode of Palin’s Ripping Yarns. Written by and starring Idle, and co-starring Neil Innes (another performer steeped in music and comedy — he was a member of the quirky British cult act Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band), it was a sketch show based around the premise of being “Britain’s smallest television network” (a premise familiar to fans of Canada’s SCTV which began a year or so later). Under-staffed and low budget, the show came and went in two abbreviated seasons and hasn’t been seen much since. Idle himself owns the rights to the show, and has indicated he has no intention of re-issuing them in any form. So what is Rutland Weekend Television’s lasting legacy? The greatest Beatles parody/homage of all time, The Rutles.

The Rutles started life as a brief sketch on RWT, featuring Idle and Innes performing an original, note-perfect recreation of the circa-1964 Lennon-McCartney songwriting style called “I Must Be In Love.” It might have gone no further, but when Idle was the guest host of Saturday Night Live in the fall of 1976, he shared some clips from RWT. The Rutles caught the attention of SNL producer (and Beatles super-fan) Lorne Michaels.

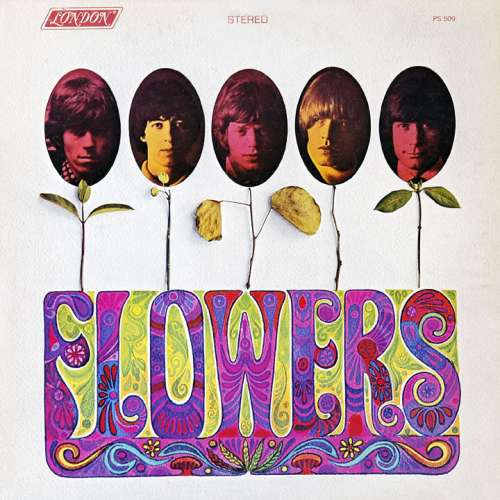

There was always a mutual admiration between Python and SNL, despite their different approaches to sketch comedy. The Python shows were meticulously written over a period of months, rehearsed, rehearsed, rehearsed, then filmed and edited tightly, weeks ahead of airtime. An average SNL episode was written on the fly in a night or two, rehearsed once (twice if there was time), and thrown at the public, ready or not, live every Saturday night. The story goes that Chevy Chase met Lorne Michaels while both were in line to see Monty Python and the Holy Grail. The younger SNL camp idolized the Pythons, and the Pythons respected the fearlessness of SNL (they said it reminded them of their early days doing nerve-wracking live revue at their universities). Idle and Michael Palin guest-hosted several times each in the show’s first five seasons.  Lorne Michaels believed there was a lot of potential in The Rutles, and produced a TV movie built around them — All You Need Is Cash. Presented as a fake documentary, Cash fleshed out the Rutles “story” from inception to break-up. From the grainy black-and-white of postwar Britain, through the colorful Pop Art and psychedelic eras, and finally the dawn of the cold, gray ’70s, Cash captured the feel of a “rockumentary” perfectly. (Just as RWT foreshadowed the more well-known SCTV, Cash beat This Is Spinal Tap to the punch by several years.) Each era got a few Innes songs that sounded so much like Beatles songs they circulated as Beatles “outtakes” on a few bootlegs. Creating style pastiches of early Beatles stuff is relatively straightforward — songs like “Hold My Hand,” “Ouch!” and “Number One” faithfully matched the energy and innocence of the early days. The band’s later, weirder era was probably more of a challenge, but the challenge was met. “Penny Lane” is recast as “Doubleback Alley,” “All You Need Is Love” is echoed by “Love Life,” and the psychedelic epic “I Am The Walrus” meets its doppelganger in “Piggy In The Middle.” And there are several others, each of them charming and matching the sound and feel of a different Beatles song…without ever becoming an outright Weird Al-style parody or stealing any of the original melodies (Innes had to go to court to prove it.) Continue reading →

Lorne Michaels believed there was a lot of potential in The Rutles, and produced a TV movie built around them — All You Need Is Cash. Presented as a fake documentary, Cash fleshed out the Rutles “story” from inception to break-up. From the grainy black-and-white of postwar Britain, through the colorful Pop Art and psychedelic eras, and finally the dawn of the cold, gray ’70s, Cash captured the feel of a “rockumentary” perfectly. (Just as RWT foreshadowed the more well-known SCTV, Cash beat This Is Spinal Tap to the punch by several years.) Each era got a few Innes songs that sounded so much like Beatles songs they circulated as Beatles “outtakes” on a few bootlegs. Creating style pastiches of early Beatles stuff is relatively straightforward — songs like “Hold My Hand,” “Ouch!” and “Number One” faithfully matched the energy and innocence of the early days. The band’s later, weirder era was probably more of a challenge, but the challenge was met. “Penny Lane” is recast as “Doubleback Alley,” “All You Need Is Love” is echoed by “Love Life,” and the psychedelic epic “I Am The Walrus” meets its doppelganger in “Piggy In The Middle.” And there are several others, each of them charming and matching the sound and feel of a different Beatles song…without ever becoming an outright Weird Al-style parody or stealing any of the original melodies (Innes had to go to court to prove it.) Continue reading →

Lorne Michaels believed there was a lot of potential in The Rutles, and produced a TV movie built around them — All You Need Is Cash. Presented as a fake documentary, Cash fleshed out the Rutles “story” from inception to break-up. From the grainy black-and-white of postwar Britain, through the colorful Pop Art and psychedelic eras, and finally the dawn of the cold, gray ’70s, Cash captured the feel of a “rockumentary” perfectly. (Just as RWT foreshadowed the more well-known SCTV, Cash beat

Lorne Michaels believed there was a lot of potential in The Rutles, and produced a TV movie built around them — All You Need Is Cash. Presented as a fake documentary, Cash fleshed out the Rutles “story” from inception to break-up. From the grainy black-and-white of postwar Britain, through the colorful Pop Art and psychedelic eras, and finally the dawn of the cold, gray ’70s, Cash captured the feel of a “rockumentary” perfectly. (Just as RWT foreshadowed the more well-known SCTV, Cash beat