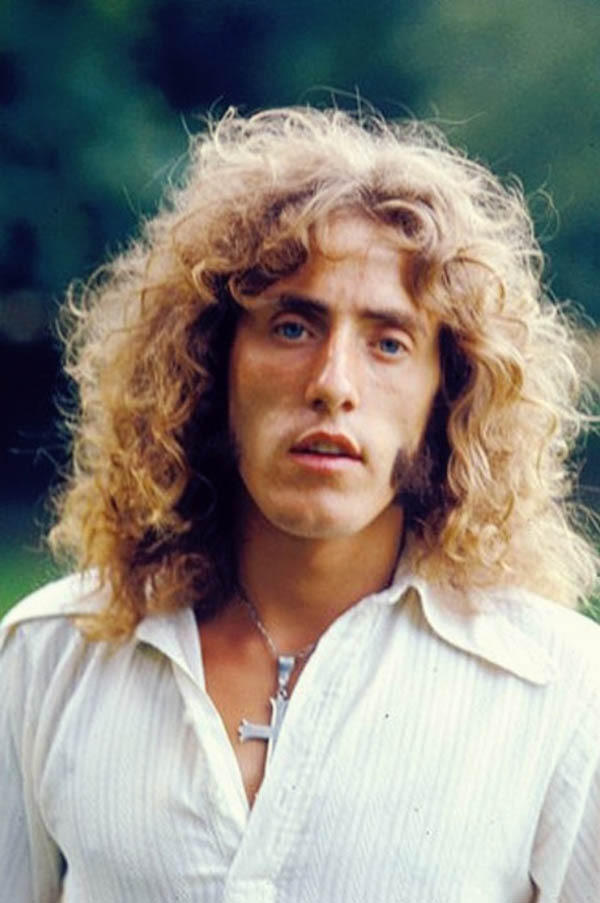

“To my mind I’ve already proved I can act. The trouble was that I used to approach acting like a rock ‘n’ roller. I was getting parts simply because of who I was. Geezers would say what a great idea it was to have a Beatle in their movie. And the fact that I wanted to act, that I felt I could act, wasn’t really the issue. But no one is going to offer Ringo Starr a top role these days just because I used to be one of the Beatles. I’ve got to be able to do the job…Maybe Caveman is the dawn of a new era for me.”

— Ringo Starr, 1980

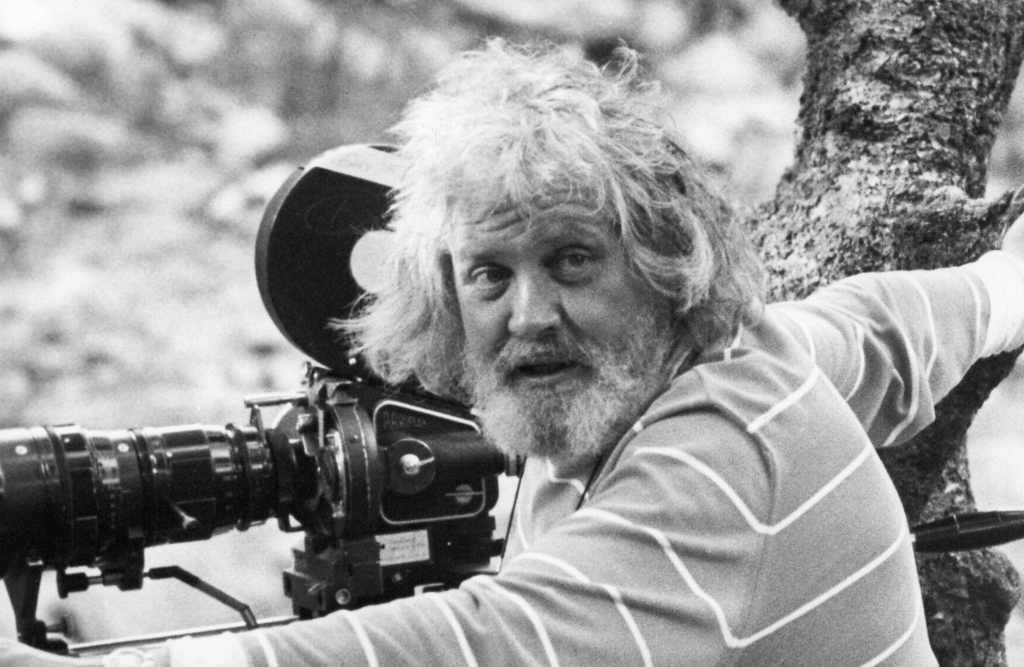

Caveman — the movie that Ringo hoped would finally launch his career as a…well, maybe not “Serious Actor,” but at least someone capable of playing a leading role — would be the feature directing debut of Carl Gottlieb. It was intended to be an homage to B-grade humans-coexisting-with-dinosaurs schlock like One Million Years B.C. and When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth, and to the silent slapstick of Chaplin and Keaton (who had both done comic “caveman” routines). The concept was not without promise, and Gottlieb had an impressive resume. Ringo had good reason to be hopeful.

Carl Gottlieb got his start in the 1964 iteration of the San Francisco improv troupe The Committee, along with guys like Howard Hesseman and Peter Bonerz. They transferred to L.A. later in the 60s, and Gottlieb moved on to TV writing before the decade was out. He scored an Emmy for writing for the controversial Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour in 1969. In addition to penning scripts for The Bob Newhart Show, All in the Family, and The Odd Couple as the ‘70s commenced, he also maintained a minor presence in the acting world, most notably in the small but dryly funny role as anesthesiologist Capt. “Ugly John” Black in Robert Altman’s 1970 feature film version of MASH.

Lightning really struck for Gottlieb in 1974 when his friend Steven Spielberg (it helps to know the right people) hired him to do a quick polish on Peter Benchley’s screenplay for Jaws. Benchley, adapting his own novel, had created a screenplay that was serviceable but not great. The characters lacked dimension and the tone was humorless and relentlessly dark. What was intended to be a one-week job blossomed into Gottlieb traveling to the Martha’s Vineyard location for the duration of the production and doing an entire re-write in close collaboration with Spielberg while shooting was underway. (He also appeared in the film as Meadows the newspaper editor.) Gottlieb’s version was a huge improvement, with likeable characters and a subtle touch of humor. Jaws went on to be the first true summer blockbuster in 1975.

Another feather in Gottlieb’s Jaws cap was his publication that same year of The Jaws Log, a book chronicling the film’s difficult production from a first-hand perspective. It became a behind-the-scenes classic in its own right among film buffs (a copy has graced the Holy Bee’s shelf since childhood), and has been updated and re-published multiple times.

Everyone’s heard the Hollywood cliche quote — “…but what I really want to do is direct.” Gottlieb was no exception, and got his chance when Steve Martin tapped him to direct his short film The Absent-Minded Waiter in 1977, which was nominated for an Academy Award. This led to him co-writing Martin’s first starring feature The Jerk (1979).

Around 1977 or ‘78, a movie producer named Lawrence Turman (The Graduate) was inspired by seeing comedian Buddy Hackett play a caveman in a Tonight Show sketch. “As a kid, I loved the film One Million B.C. [the 1940 version with Victor Mature], and the thought of doing a picture like that, using the same wardrobe and the same language, but played for laughs, seemed like a great idea.”

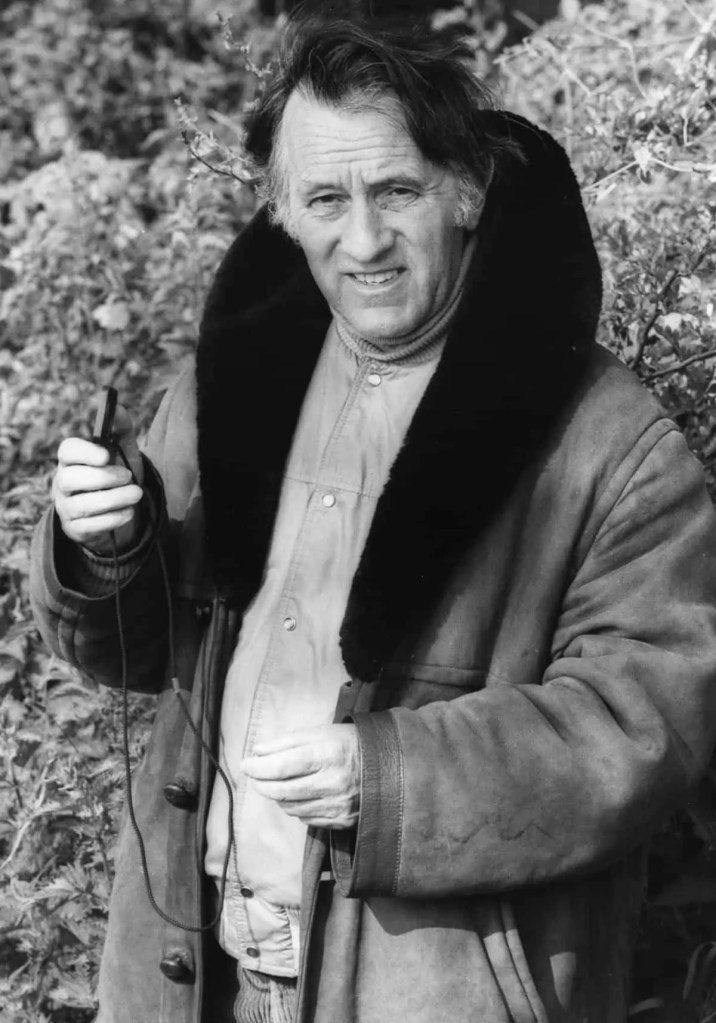

Turman and his producing partner David Foster hired Gottlieb and Rudy De Luca (fellow TV writer and frequent Mel Brooks collaborator) to do a screenplay based on this idea. Trusting Gottlieb’s comedy instincts, the producers decided to have him direct as well. Although they felt Gottlieb was on solid ground humor-wise, they hedged their bets when it came to the rookie director’s handling of visual effects. They brought in stop-motion guru Jim Danforth, who had done the effects on Caveman’s inspiration One Million Years B.C. and similar films, to direct all the sequences with the dinosaurs. He would be credited as a co-director with Gottlieb.

“When we wrote the movie, it required a clever but small person, not someone with an imposing stature,” said Gottlieb. “We wrote it without an actor in mind, and then, when the screenplay was finished, we were looking at Dudley Moore or Ringo…Those were the choices. Dudley was unavailable and we went with Ringo because we met with him and found out he was interested in doing it…I told him this was not like anything he’s done before. It didn’t depend on his being a Beatle or a famous person — it’s actually an odd, funny little acting part.”

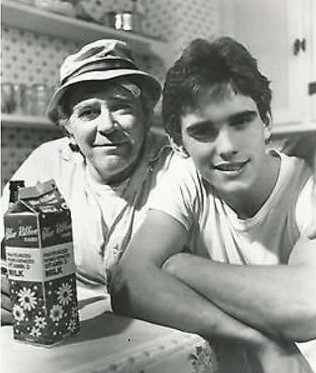

Filming began in February 1980 in Sierra de Organos National Park outside of Durango, Mexico. Joining Ringo in the cast were Dennis Quaid, Shelley Long (two years before Cheers), football legend John Matuszak, former Bond girl Barbara Bach (The Spy Who Loved Me), and veteran comic actors Avery Schreiber and Jack Gilford (if you don’t know their names, you know their faces).

Armed federales surrounded the location each day to protect the production from pillaging by the local bandits — and to make sure the visiting Americans had no narcotics, meaning the cocaine-loving Ringo had to do without, so he doubled down on his alcohol intake. He brought along his friend Keith Allison to be his “minder,” making sure he made it on set each morning in relatively decent shape after long nights in Mexican cantinas.

About two-thirds of the way through production, word came through from the Director’s Guild that Jim Danforth would not be allowed a co-director’s credit for directing the dinosaur sequences. He walked off the project. Gottlieb would receive sole credit as director. Danforth declined any onscreen credit, so visual effects are credited to his partner David Allen (who would later go on to do some great stuff for George Lucas’s effects company Industrial Light & Magic).

The bulk of the location work was done at Sierra de Organos, followed by a week in Puerto Vallarta, and concluding with soundstage work at Churubusco Studios in Mexico City. As production proceeded, Ringo and castmate Barbara Bach found themselves in a developing relationship. After rehearsing a comedic “seduction” sequence with each other the night before the scene was shot, Ringo lingered in Bach’s hotel room after everyone else had left, and the couple showed up the next morning hand-in-hand. Bach was unawed by Ringo’s storied past. “I was never that much of a Beatles fan, which made it easier,” Bach said. “I just treated him like everyone else.”

Despite the credit dust-up with Danforth and a few queasy mornings with hungover cast members, shooting went smoothly and was all over within six weeks. Everyone had gotten along famously and went home satisfied with the results.

CAVEMAN

Released: April 17, 1981

Director: Carl Gottlieb

Producers: Lawrence Turman, David Foster

Screenwriters: Carl Gottlieb, Rudy De Luca

Studio: United Artists

Cast: Ringo Starr, Barbara Bach, Dennis Quaid, Shelley Long, John Matuszak, Avery Schrieber, Jack Gilford, Evan Kim, Ed Greenberg, Cork Hubbert, Mark King, Carl Lumbly

Caveman tells the story of Atouk (Ringo), a meek and put-upon prehistoric cave dweller in the year “one zillion B.C.” The leader of his tribe is Tonda (John Matuszak), a bullying alpha male who forces his food-gathering expedition to abandon slow-witted Lar (Dennis Quaid) when he is injured in a dinosaur attack triggered by Atouk. Tonda also has a beautiful mate Lana (Barbara Bach), with whom Atouk is secretly in love. Atouk is already on the outs with the tribe for bungling the expedition, and finds himself cast out entirely when he is caught attempting to “seduce” Lana (after drugging her with sleep-inducing berries, which is pretty creepy).

Out in the wilderness, Atouk is reunited with Lar, and the two begin gathering other outcasts together into a “misfit” tribe, beginning with Tala (Shelley Long) and her blind father Gog (Jack Gilford), and eventually including a dwarf, a gay couple, and Nook (Evan Kim), who happens to speak perfect modern English. (The rest of the misfits find him totally incomprehensible.) The misfit tribe’s discoveries include standing erect, music, fire, and cooking. They also create weapons and armor, allowing them to strike up a rivalry with Atouk’s original tribe. There are multiple encounters with Danforth-designed dinosaurs, and a run-in with the Abominable Snowman before the whole thing ends up with Tonda vanquished and Atouk being acknowledged as leader of the combined tribes. Atouk ends up choosing Tala over the shallow Lana, and “they lived happily ever after” as the onscreen words tell us.

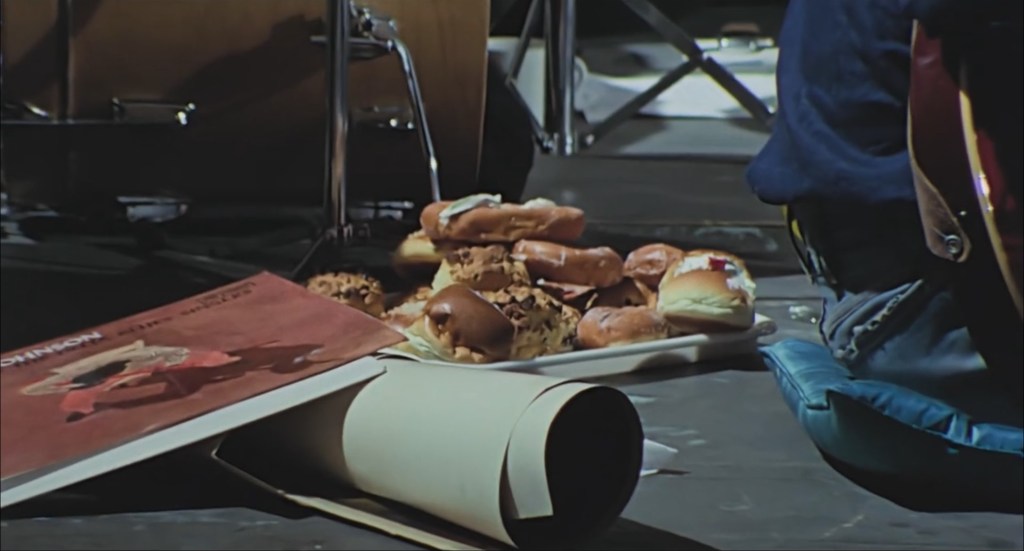

Whether or not it was Gottlieb’s intent, what he ended up with is essentially a stoner comedy. The broad, basic humor is the textbook definition of “sophomoric” and perhaps very appealing to someone watching this glazed-over high at two in the morning. The film is reaching for a kind of sweet silliness, but too often comes off as just really, really dumb. It’s almost as though Gottlieb and De Luca secretly passed off their screenwriting duties to a group of fifth-grade boys. Falling into something (water or ideally something grosser), or simply falling over, is considered the pinnacle of comedy. Cartoon sound effects are employed to an extreme degree. Fart jokes and poop jokes abound.

The one element that seems to work well is that the dialogue consists of about fifteen nonsense words in “cavespeak,” so most of the acting is done through grunts, pantomime, and facial expressions…and the performers are clearly having a great time working that way. Dialogue was always Ringo’s Achilles’ heel, and now he could eschew his flat Liverpool monotone and rely on his natural physicality and expressive eyes. Shelley Long also came off very well and is kind of adorable, not yet associated with her uptight Diane Chambers character. In fact, the only one who seems a little stiff and hesitant is Barbara Bach. The animated dinosaurs are actually pretty charming, and for the most part steal the show.

When all is said and done, Caveman is a harmless little film that feels interminably long at barely 90 minutes. Despite Lawrence Turman’s moment of inspiration, perhaps “comedic cavemen” is a concept best left to Buddy Hackett sketches and Charlie Chaplin shorts.

The reviews were surprisingly kind. The New York Times called it “nicely whimsical,” and the Village Voice went so far as to use the term “enchanting.” Newsday went with “infantile, but also playful and appealingly good-natured.” The Washington Post was a little more realistic: “Priceless it ain’t, but if the kids are determined to enjoy it, the brain damage should be minimal.” Ringo was also singled out for praise, with many comparing his performance favorably with his Beatles films. It generated a mediocre $16 million at the box office, but the budget was only $6.5 million.

So what happened? No one seems to know. Despite the good reviews for his performance, and despite the fact that, all things considered, Caveman was far from a disaster, Ringo was never offered another major film role again.

Carl Gottlieb went on to direct two sequences in the 1987 cult anthology film Amazon Women on the Moon. Each of his sequences perfectly encapsulates the two Gottlieb directing styles — “Pethouse Video” was obvious and crass, and “Son of the Invisible Man” was subtle and clever. (He wrote neither.) He hasn’t directed since, nor has he written anything of note since the ‘80s.

Ten days after Caveman’s release, Ringo and Barbara Bach were married at Marylebone Town Hall in London. Now happily (if blearily) hitched, he was still barely keeping his head above water career-wise. No movie producers were calling him. His most recent solo album, Stop and Smell the Roses (October 1981) sold about six copies and is now widely regarded as one of the worst of all Beatle solo albums. He was dropped by yet another record label. His heavy drinking continued unabated, and his new spouse joined in. “Every couple of months she’d try and straighten us out,” Ringo said. “But then we’d fall right back in the trap.”

His next — and to date, final — movie role was handed to him by an old friend: Paul McCartney. He was to play a drummer in Paul’s band. Not too much of a stretch.

Continue reading