“It took God six days to create the Heavens and the Earth, and Monty Python ninety minutes to screw it up.” — Original film poster tagline.

SPOILER ALERT: The meaning of life, according to Monty Python, will be revealed in this blog entry.

Here at Holy Bee World Headquarters (i.e., the second-hand desk in my converted garage), I generally try to use my “Recommends” feature to champion something that may be existing in relative obscurity, but just as often I will use it to highlight something in popular culture that is definitely on the radar, but doesn’t get the respect it may deserve.

Here at Holy Bee World Headquarters (i.e., the second-hand desk in my converted garage), I generally try to use my “Recommends” feature to champion something that may be existing in relative obscurity, but just as often I will use it to highlight something in popular culture that is definitely on the radar, but doesn’t get the respect it may deserve.

Britain’s Monty Python comedy team (John Cleese, Eric Idle, Terry Jones, Michael Palin, the late Graham Chapman, and American animator Terry Gilliam) certainly isn’t obscure. But while every nerd over 40 in America can quote 1975’s Monty Python and the Holy Grail at length, and the Brits have taken 1979’s Monty Python’s Life of Brian to their collective bosom, The Meaning of Life, a collection of sketches (sort of) exploring the purpose of existence, is treated as something of an also-ran…even though a mention of any of its scenes will elicit a chuckle and a quote from any Python fan (“wah-fer thin mint” is a common favorite), just like all the other of the team’s productions.

A few of the Pythons themselves are somewhat dismissive of the 1983 film that would prove the swan-song for the full six-member group. “We started work on it before any of us deep-down wanted to,” said John Cleese, who ended up the most frustrated with the project. “It wasn’t all bad, just aimless.” Even Terry Jones, the film’s champion, admitted the writing process was labored. “It was getting increasingly hard to get [the six of us] together, and it showed.”

So, what prompted the Holy Bee to take up the cause of everyone’s least favorite Python  film?

film?

While cleaning and organizing a musty bookcase in the aforementioned World Headquarters, I came across a forgotten DVD still in the shrink-wrap — Monty Python Live (Mostly): One Down, Five To Go, which documented their July 2014 reunion stage show at London’s O2 arena. (The title is a reference to Graham Chapman’s 1989 death.) Reunion rumors had swirled around the group for three decades, but the reason that finally forced the five remaining members on to the stage one final time was pretty prosaic — they needed the money. (Holy Grail producer Mark Forstater successfully sued the group for almost a million pounds in royalties on Spamalot, Idle’s Broadway musical based on the film.) I cracked open the DVD and found myself enjoying the reunion show quite a bit — several “greatest hits” sketches that everyone knows, and a few deep cuts for hardcore fanatics, performed with all the energy a group of men in their seventies could muster (at least two of them with artificial hips). The whole thing was presented as a gala stage extrvaganza, with massive production numbers backed by a full team of dancers and an orchestra. The team swapped some roles around and divided up Chapman’s parts among themselves (all six very rarely appeared in sketches at the same time anyway), and pulled off an overlong and slightly overbaked semi-reunion that was still a lot of fun.

Then…it struck me that it was now, for all intents and purposes, two down, four to go. The O2 shows were Terry Jones’ final performances. All throughout the rehearsals and the series of ten performances, Jones struggled with remembering his lines, even in material he had performed hundreds of times. (The others, with their usual sensitivity, referred to anyone forgetting their lines as “pulling a Terry.”) The following year, he was diagnosed with primary progressive aphasia, a form of dementia. Unlike Alzheimer’s, PPA does not affect orientation or cognition, but it has a devastating effect on the ability to communicate. As of this writing, Jones, 76, is still living comfortably, but cannot write and cannot speak beyond a few garbled words. [EDIT: Jones passed away Jan. 2020.]

Watching their reunion show, and thinking sadly of Terry Jones’ illness and retirement, I decided to binge watch the three original Python films — all of them directed by Jones. (Holy Grail was co-directed with Gilliam.)

(Their “official” filmography consists of five movies but their first, 1971’s And Now For Something Completely Different, consists of re-filmed sketches from their late 60s – early 70s BBC-TV series and shouldn’t really count. And Monty Python Live at the Hollywood Bowl, a videotaped record of their 1980 live show, was intended to be shown on HBO or Showtime. It was instead transferred to film and placed in very limited theatrical release — against the team’s wishes — in 1982.)

Grail and Brian came off as the unimpeachable classics they are, but I was struck this time by how well-done The Meaning of Life was. It looks great. Jones’ directorial eye has a good sense of color, the overall production design really pops, and he stages the musical sequences as well as any traditional musical director. The humor of Life has a reputation for being patchy, but here’s the claim on which I’m basing this entire blog entry — I’d put the first half (45 minutes or so) of The Meaning of Life up against anything they ever produced and it would come out equal — in terms of wicked satire, plain belly laughs, and the aforementioned visual sophistication, which Python realized was important for a feature film, even if it was just a collection of rather silly sketches.

In the group’s eyes, the film’s nagging flaw was that it never found an organizing theme until the very end of the scripting process, denying it the opportunity for a final polish. They had just been writing random sketches, hoping to eventually concoct a framework on which to hang them. Grail and Brian had been narrative films, with a story that consistently followed the main character(s) from beginning to end. After those experiences, Jones in particular wanted to try a sketch film, mostly for the challenge. “[Cleese] had this theory that you can’t make a sketch film over fifty minutes,” Jones stated. “I always said ‘I’m sure we can do a sketch film and make it work,’ just to show we can.” By the time they came up with the “meaning of life” concept, they were up against deadlines. “I think it would have been perfect if had we given it one extra draft,” said Eric Idle. “We just sort of stuck in references to the meaning of life wherever we could.”

The film’s seven sections represented (sort of) the Seven Ages of Man. They linked the sections together with sequences of the six Pythons as fish in the fish tank of a fancy restaurant, pondering over their all-too-short remaining time on earth.

“Oh, look. Howard’s being eaten.” “Makes you think, doesn’t it?” “I mean, what’s it all about?”

With their biggest budget yet (a whopping $9 million), the The Meaning of Life was filmed at EMI Elstree Studios in London and on location in Lancashire, Yorkshire, and near Glasgow, Scotland over the summer of 1982. With Jones helming the main film, Terry Gilliam, by then a respected director in his own right (he had just done Time Bandits) was put in charge of directing a “special sequence” that would pop up two-thirds of the way through. This  fantasy segment, The Crimson Permanent Assurance, features a group of elderly accountants violently turning on their younger corporate masters, and “sailing” their crumbling little building, pirate ship-style, on a raid through the sleek skyscrapers of the City of London. The sequence grew lengthier and more elaborate, and took as long to shoot as the main film. (“No one told me to stop,” said Gilliam, unapologetically.) After viewing the first edit, the team realized it would no longer comfortably fit in the space it was assigned to. They cut most of it out and presented it as a separate short film running ahead of the main feature.

fantasy segment, The Crimson Permanent Assurance, features a group of elderly accountants violently turning on their younger corporate masters, and “sailing” their crumbling little building, pirate ship-style, on a raid through the sleek skyscrapers of the City of London. The sequence grew lengthier and more elaborate, and took as long to shoot as the main film. (“No one told me to stop,” said Gilliam, unapologetically.) After viewing the first edit, the team realized it would no longer comfortably fit in the space it was assigned to. They cut most of it out and presented it as a separate short film running ahead of the main feature.

I have to say, visually sumptuous as it is, I always skip The Crimson Permanent Assurance whenever I pop in the movie, and go straight to The Meaning of Life proper.

As I stated earlier, the film opens strong. Part I: The Miracle of Birth has two segments — one depicting a birth in a sterile modern hospital, and the other in the “Third World,” which in the Pythons’ minds is the coal-mining region of Yorkshire. In the modern birth sequence, the mother is made entirely secondary to the bureaucracy of the hospital in general, and the technology of the delivery room in particular. (Mother: “What do I do?” Doctor: “Nothing, dear, you’re not qualified.”)

“This is the machine that goes ‘ping!'” “And this is the most expensive machine in the whole hospital.” “Aren’t you lucky!”

The “Third World” sequence depicts a working-class Catholic family with hundreds of kids, all of whom are about to be permanently shipped off to a dire fate due to crushing poverty. Although at polar opposites of the social spectrum, both segments make the point that our cruel world’s attempts at de-humanization begin at birth.

“I’m afraid I have to sell you all for medical experiments. God has blessed us so much, I can’t afford to feed you anymore.”

The sequence then explodes into what may be one of the top five moments of Python ever: the larger-than-life musical number “Every Sperm Is Sacred.” With all the singing and dancing children, it looks straight out of Annie, but it’s actually a pretty scathing take-down of the Catholic Church’s backwards and short-sighted views on responsible birth control. The Protestants get theirs next (though not as elaborately) as the sexually-repressed Protestant couple across the street view all of this with sniffy disdain and a misplaced sense of middle-class superiority.

“Every sperm is sacred/Every sperm is great/If a sperm is wasted/God gets quite irate”

At this point, the film dodges a bullet. The next sequence was supposed to be “The Adventures of Martin Luther,” depicting the 16th century theologian as a creepy pervert trying (and failing) to redirect his obsession with young girls into a fixation on spoons. (Yes, spoons.) It was cut out of the movie just before its release, and with good reason. It’s terrible. Short as it is, had it been in the film, it would have been a major stumble. (It’s included as a bonus feature on the Blu-Ray. Don’t bother.)

Luckily, the Pythons’ good editorial judgment prevailed, and Life continues to go from strength to strength. Part II: Growth and Learning opens in the chapel of a boys’ parochial boarding school, where the vicar leads them in a groveling prayer and hymn (“O Lord, Please Don’t Burn Us”) and the headmaster lectures them against rubbing linseed oil into the school cormorant. (I’m still trying to figure that one out.) (Pointless trivia — as the vicar, Michael Palin is sporting a real moustache, not one of the usual Python glue-on jobs. This was the first day of shooting, and Palin had just finished playing a moustached vicar in the film The Missionary.) The scene then shifts to a classroom, where the headmaster is giving a sex education lecture — followed by a full-on demonstration with his “good lady wife.” (“We’ll take the foreplay as read, if you don’t mind, dear…”) The students remain impassive. Institutionalized education can drain the fun out of anything.

“Wymer! This is for your benefit, will you kindly wake up. I’ve no intention of going through this all again!”

Part III: Fighting Each Other opens with a brief but very funny sequence dealing with a birthday celebration in a World War I trench, goes on to take some satirical jabs at the modern British Army, then settles into a longer historical sequence set during the Zulu Wars of the late 1800s, wherein a British officer has had his leg chopped off and stolen by a pair of lunatics in a tiger costume. (“I’ll organize a party right away.” “Well, it’s hardly the time for that.” “A search party, sir.” “Ah. Much better idea.”)

“Oh, a leg! You’re looking for a leg. I think there is one in there, actually…”

At this point, we have arrived at what the Pythons proudly announce as “The Middle of the Film,” and invite the viewing audience to play along with a game called “Find the Fish.” This sequence is so bizarre and surreal that words don’t do it justice, so I’ll just include an image below:

“Ooohhhhhh, fishy, fishy, fishy, fish!”

The second half opens with Part IV: Middle Age, and we hit our first big weak spot. Maybe there’s something to Cleese’s fifty-minute theory after all. The Hendys are a boring middle-aged American couple on vacation, and dining in a dungeon-themed Hawaiian restaurant. They have little of interest to say to each other, and therefore are pleased to discover that the menu, in addition to food, offers conversation topics. They choose “philosophy,” and struggle mightily with it because they aren’t very bright. They end up asking the waiter to send it back because “it isn’t very good.” The Hendys are an easy “ignorant American tourist” stereotype, well-meaning but dense, and the  whole awkward, over-long sequence falls totally flat. (In the original pre-release cut, the scene went on even longer. Again, good editorial sense prevailed.) A-for-effort to Eric Idle in drag as the cheerily vacant Mrs. Hendy, and Cleese tries out an atrocious American accent as the bluff, crew-cutted Midwestern waiter enthusing over the “Steelers-Bears game” (a divsional impossibility, as one is in the AFC and the other in the NFC — silly Brits.) Luckily for us, the waiter offers a specialty topic “off the menu” — Part V: Live Organ Transplants, and the movie revives itself and goes on another hot streak.

whole awkward, over-long sequence falls totally flat. (In the original pre-release cut, the scene went on even longer. Again, good editorial sense prevailed.) A-for-effort to Eric Idle in drag as the cheerily vacant Mrs. Hendy, and Cleese tries out an atrocious American accent as the bluff, crew-cutted Midwestern waiter enthusing over the “Steelers-Bears game” (a divsional impossibility, as one is in the AFC and the other in the NFC — silly Brits.) Luckily for us, the waiter offers a specialty topic “off the menu” — Part V: Live Organ Transplants, and the movie revives itself and goes on another hot streak.

A pair of men in white smocks knock at the door of Mr. Brown. (Brown is played by Terry Gilliam, who did not perform on camera very much, but when he did, he made it count — his characters are the most grotesque and bizarre in the Python canon. He chooses to play “Mr. Brown” as a cigar-chomping Jewish Rastafarian.) The men have come for his liver. Of course Brown objects, as he’s still using his liver. They throw him against the wall and pull out his wallet. “What’s this, then?” “A liver donor’s card.” “Need we say more?”

“The card says ‘in the event of death’!” “No one who’s ever had their liver taken out by us has survived.”

They manhandle him onto his dining room table and proceed to remove his liver with a carving knife, saw, and bolt-cutters, causing blood and slippery viscera to be strewn everywhere. Mrs. Brown observes the whole thing without much interest before inviting one of the men into the kitchen for a cup of tea. (“I thought she’d never ask.”) When asked if she would be willing to donate her liver, Mrs. Brown begs off, saying she’s scared to die. We then move into the next major musical sequence of the film, the amazing “Galaxy Song,” a tour of the Milky Way with a bouncy tune and astronomically accurate (or “approximately accurate as of 1983”) lyrics. Mrs. Brown, newly aware of her small role in the staggeringly immense universe, agrees to donate her liver, and the smocked workman fetches his tools…

“Just remember that you’re standing on a planet that’s evolving/And revolving at 900 miles an hour/That’s orbiting at 19 miles a second so it’s reckoned/A sun that is the source of all our power”

Cut to the boardroom of the Very Big Corporation of America, where important businessmen are discussing the meaning of life. (“1. People are not wearing enough hats. 2. Matter is energy. In the universe, there are many energy fields which we cannot normally perceive. Some energies have a spiritual source which act upon a person’s soul. However, this soul does not exist ab initio, as orthodox Christianity teaches. It has to be brought into existence by a process of guided self-observation. However, this is rarely achieved, owing to man’s unique ability to be distracted from spiritual matters by everyday trivia.” “What was that about hats again?”) The Crimson Permanent Assurance sequence was supposed to go here as the boardroom is attacked by the elderly piratical accountants, but only a brief fragment remains.

Part VI: The Autumn Years opens on a Noel Coward-type pianist entertaining the clientele of an upscale restaurant with the ribald but “frightfully witty” “Penis Song.” The refined atmosphere is disturbed by the arrival of Mr. Creosote, an ill-tempered, foul-mouthed and grotesquely obese gentlemen who crams his thousand-pound bulk into a custom-tailored tuxedo and appears to be a regular customer. The obsequious French maitre’d fawns over him — Creosote is clearly very wealthy — and meets his every request, including one for a bucket, which he proceeds to copiously vomit into…then onto the floor, the menu, the table, the maitre’d’s trousers, the cleaning lady, etc. etc., all while managing to eat everything on offer. The other patrons try to ignore the disgusting display, or attempt to discreetly leave without making too much of a fuss. The sequence ends with the infamous “wah-fer-thin mint” for dessert, which causes the ever-swelling Creosote to finally explode, showering part of the restaurant with partially-digested food and internal organs.

Part VI: The Autumn Years opens on a Noel Coward-type pianist entertaining the clientele of an upscale restaurant with the ribald but “frightfully witty” “Penis Song.” The refined atmosphere is disturbed by the arrival of Mr. Creosote, an ill-tempered, foul-mouthed and grotesquely obese gentlemen who crams his thousand-pound bulk into a custom-tailored tuxedo and appears to be a regular customer. The obsequious French maitre’d fawns over him — Creosote is clearly very wealthy — and meets his every request, including one for a bucket, which he proceeds to copiously vomit into…then onto the floor, the menu, the table, the maitre’d’s trousers, the cleaning lady, etc. etc., all while managing to eat everything on offer. The other patrons try to ignore the disgusting display, or attempt to discreetly leave without making too much of a fuss. The sequence ends with the infamous “wah-fer-thin mint” for dessert, which causes the ever-swelling Creosote to finally explode, showering part of the restaurant with partially-digested food and internal organs.

This is the most notorious scene in the whole film, and at this point we have to ask ourselves, as Roger Ebert did in his original review, what point are they trying to make here? On what level is this working? By their own admission, it’s mostly just gleeful, gross-out boundary-pushing of a distinctly juvenile stripe, but they have hinted that it has a slightly deeper message — a little social commentary on how the British upper class can get away with the most appalling and boorish behavior and no one ever calls them on it. Because of their status, they are continually indulged and have excuses made for them. The people offended feel in the wrong somehow. The sketch (written by Terry Jones, who also played Creosote) almost didn’t make the final screenplay, but it was saved by Cleese (who normally disdains bodily-function humor) because he thought the French maitre’d character was hilarious and he wanted to play him. (And the whole thing really has nothing to do with the “Autumn Years,” re-inforcing the random-sketches-forced-into-a-format origin story of the film.)

“Tut tut tut! I hope monsieur was not overdoing it last night…”

As the restaurant staff cleans up the Creosote aftermath, a world-weary waiter tries to explain his view of the meaning of life before growing defensive over its simplicity: “‘Love everyone, try to make everyone happy, and bring peace and contentment everywhere you go.’ And so, I became a waiter. Well…it’s not much of a philosophy, I know…but, well… fuck you…”

The film strikes another off-note at the start of Part VII: Death, which features a condemned criminal being executed by a method of his own choosing: chased off a cliff by a large group of beautiful — and topless — women. I don’t have any problem with nudity (comedic or otherwise), but this just seems a little below the Pythons, especially the running-in-slow-motion bit. Ever self-aware, the Pythons admit they’re grabbing low-hanging fruit by having the condemned man’s crime be “the making of gratuitous sexist jokes in a moving picture.” I suppose I’m putting them on too high a pedastal. They’ve used nude women for comedic purposes before, but it always seemed balanced by the team’s own lack of hesitation to drop their clothes if the scene required it.

The final sequence has the Grim Reaper invading a painfully bourgeois dinner party, and hauling the guests — who have all died eating tainted salmon mousse — off to Heaven. (Python rarely ad-libbed. They were writers at heart, and stuck to their scripts. However, Palin’s improvised line — “I didn’t even eat the mousse!” — was kept in the film.)

“Uh, it’s a Mr. Death or something, and he’s come about the reaping? I don’t think we need any at the moment…” “I am the Grim Reaper.” “Hardly surprising in this weather.”

The final major musical sequence depicts Heaven as a Las Vegas-style show room where “it’s Christmas every day.” All the characters who died in the film (the Browns, the Catholic kids, Zulu War soldiers, etc.) are in the audience as a smarmy, Tony Bennett-esque Vegas crooner closes the film with “Christmas In Heaven.”

“It’s Christmas in Heaven, the snow falls from the sky/But it’s nice and warm and everyone looks smart and wears a tie/It’s Chistmas in Heaven, there’s great films on TV/The Sound of Music twice an hour and Jaws I, II, and III“

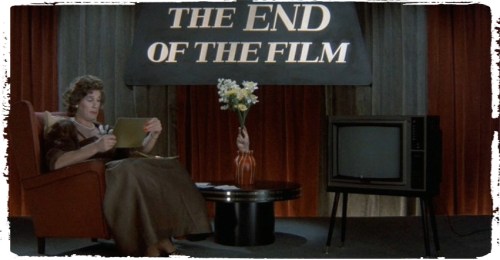

As the song concludes, we reach the End of the Film, and a distinguished lady hostess reveals the meaning of life. “It’s nothing very special: Try and be nice to people, avoid eating fat, read a good book every now and then, get some walking in, and try and live together in peace and harmony with people of all creeds and nations…Here’s the theme music. Good night.”

Then the old BBC Monty Python’s Flying Circus animated opening credits begin playing on a TV screen, which begins slowly drifting off into space, symbolizing the end of the original group. As the Python theme fades out, a reprise of the “Galaxy Song” fades in and the film credits begin scrolling up the screen. “I felt it was over after The Meaning of Life,” said Terry Gilliam. “We all get to Heaven, don’t we? That was really the end of Python as such.”

“And finally here are some completely gratutious pictures of penises to annoy the censors and hopefully spark some sort of controversy which it seems is the only way to get the jaded, video-sated public off their fucking arses and back in the sodding cinema. ‘Family entertainment,’ bollocks! What people want is filth.”

Terry Jones once said “I still think that there are bits of The Meaning of Life that are the best things we ever did.” I agree. “Birth,” “Every Sperm Is Sacred,” “Protestant Couple,” “O, Lord Please Don’t Burn Us,” “Sex Lesson,” “Missing Leg,” “Live Organ Transplants,” “Galaxy Song,” “Mr. Creosote,” “Grim Reaper,” and “Christmas In Heaven” can be ranked among some of the best comedy sequences ever. There are lots of other quality nuggets I didn’t even mention. Eric Idle, somewhat backhandedly, agrees. “It’s gross, it’s nasty, it’s violent…It’s got some classic Python moments in it.”

The film was entered into competition at the Cannes Film Festival, where it won the Special Jury Prize (essentially second place after the Palm d’Or). Jones’ acceptance speech addressed the selection jury: “Your money is behind the wash basin.”

Going topless in Cannes, May 1983

“This movie is so far beyond good taste, and so cheerfully beyond, that we almost feel we’re being one-upped if we allow ourselves to be offended…A barbed, uncompromising attack on generally observed community standards.”

— Roger Ebert, Chicago Sun-Times

“The Ben Hur of sketch films, which is to say that it’s a tiny bit out of proportion.”

— Vincent Canby, New York Times

The film was released in the spring of 1983. It didn’t exactly cause lines around the block, but at least it got banned in a few countries, turned a tidy profit, and was deemed an appropriate send-off for the beloved comedy troupe.

All this is more than enough justification for The Meaning of Life to earn a recommendation by the Holy Bee. If you haven’t seen it for awhile, give it another chance (ideally on an empty stomach.)

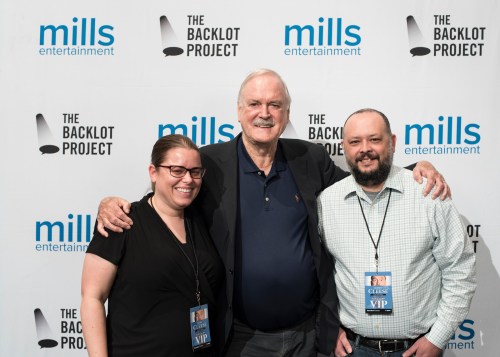

I got the opportunity to meet John Cleese recently. As the proud owners of Very Important Person lanyards at one of his recent Q&A performances, my wife and I earned the privelege of post-show coffee and canapes, a photo, and a moment of his time. I decided to ask him about the meaning of life, for real.

As I approached the Great Man, his face lit up. “That’s a marvelous beard you have,” he enthused in that distinctive Cleesian voice (you can hear him saying it in your head right now, can’t you?) My salt-and-pepper facial hair actually bears a resemblence to Cleese’s own in 1985’s Silverado, but it didn’t occur to me to mention it, because before I knew it, he had reached out a lanky arm to gingerly tilt my face closer to his for further examination. “Your nasal hair hasn’t grown into your moustache yet,” he noted approvingly. And then he was on to the next Very Important Person, and that is as close to the meaning of life as I’m ever going to get.

It’s enough.

The Very Important Holy Bee & the Even More Important Mrs. The Holy Bee have a random, totally unplanned encounter with a legend. No silly walks were performed.

SOURCES for the Python quotes include the DVD commentary, the oral histories Monty Python Speaks! and The Pythons’ Autobiography by The Pythons, and Kim “Howard” Johnson’s The First 20 Years of Monty Python.

GREAT that you really got to meet this icon…. and for him to notice your beard and nose hairs… .is hilarious !! Well done!

Pingback: Monty Python: The Albums (Part 4) | Holy Bee of Ephesus