Five Days At Memorial: Life and Death in a Storm-Ravaged Hospital by Sheri Fink

For such an historic event, I can’t seem to find any books about Hurricane Katrina that detail the events in a straightforward way. Some get all science-y, describing the meteorological features of the storm itself, the engineering of the levees, and other things way over the head of a dumb bunny like myself. Many (many) more get all sociopolitical-y, describing in long-winded detail the economic gulf between class and race in New Orleans, and the government’s response (or lack thereof) in the aftermath of the disaster. Very few give a general narrative, or overview of exactly what happened to the city over those few days in August 2005. The human moments and survival, or non-survival, stories that make for the most gripping reading are sprinkled through these books, but never take center stage.

Five Days At Memorial has all the elements I’m looking for, but focused in on a single location. It’s the story of Hurricane Katrina told through its impact on one building and its occupants — Memorial Medical Center in downtown New Orleans. Within hours of the storm’s landfall, the building had no power, no plumbing, and no ground access to anywhere due to the massive floods that turned streets into rivers.

We are a wired society, folks, no two ways about it. Lose electrical power for a few hours, and everyone goes into Little House on the Prairie mode, lighting candles and playing board games and having a fine old time. Lose it for more than a day, and it’s Road Warrior — society shits it collective pants in a shuddering seizure, grinding to a halt as people loot, rape and riot. Power loss is particularly catastrophic in a hospital. Respirators, monitors, climate control, and almost every piece of life-preserving equipment all plug into an outlet. Which is why hospitals always have back-up generators. Now why a city that’s below sea level and has suffered catastrophic floods in the past would choose to place a major hospital’s emergency generators in the basement is something of a head-scratcher. Generators under several feet of water do not operate at peak efficiency. In fact, they do not operate at all.

So Memorial became a hot, humid prison awash in human sewage, and forced the hardy souls who were stuck there to wait for days in hope of rescue. Helicopters and boats were limited in number and capacity, needed by thousands all over the city, and poorly coordinated to begin with. Not only did Memorial have to contend with harrowing physical circumstances, some of their none-too-spry patients left them with ethical dilemmas as well. Who gets priority rescue — those in the worst shape and closest to death, or those with a better chance for a longer life? What do you do with hospice patients who would be gone in a matter of days, hurricane or not, and now have no respirators or pain-killers to ease their way out? Do you force them to linger painfully, or put them out of their misery? If the latter, at what point in the ordeal is it acceptable, and which ones? Who decides? And who actually does the deed?

The Memorial staff had to answer all of these questions, act upon their decisions under extreme duress, and live with the consequences. Fink does a great job at telling their stories without editorializing or moralizing, and makes me grateful for my fully-functional, above-sea-level electrical grid.

(Whatever happened to “fink” as an insult, anyway? You don’t hear it much anymore.)

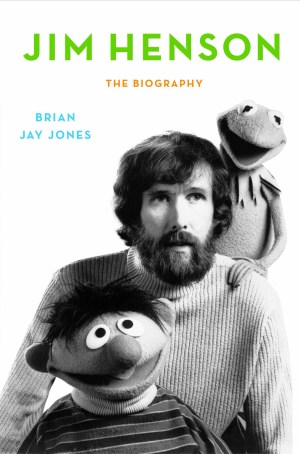

Jim Henson: The Biography by Brian Jay Jones

We’ve touched on the topic of human complexity exposed by the biographer’s unblinking eye in the previous post, but if you’re looking for Johnny Cash-style darkness in the life of Jim Henson, you won’t find it. Henson was, by all accounts, a generally pleasant man.

That doesn’t mean he wasn’t complex, however. I was reminded of two other highly recommended biographies I’ve read in recent years: Walt Disney by Neal Gabler and Schulz and Peanuts by David Michaelis. All three books deal with men who created beloved and heartwarming characters, but had difficulties in personal relationships with friends and family that were partly due to shyness and a naturally reserved nature, but mostly because of a completely inward-facing and unstoppable creative drive that shut closeness to most other people out. They also created massive and successful business empires, of which they were the undisputed boss. Even if they did not necessarily rule with an iron fist, it was made quite clear to everyone who was in charge, and two was a crowd at the top of their mountain.

There were a few surprises in the book that I was pleased to discover. Despite his easygoing hippie-ish demeanor, Henson had a very wicked sense of humor. (In an in-house test reel made to introduce the Muppets to the creators of still-untitled Sesame Street, Children’s Television Workshop, an unnamed Muppet remarks, “This show’s for kids who can’t read? Howzabout calling it Hey, Stupid!”) He had no problem with creative and prolific profanity, a trait he shared with the other Muppeteers. (The Sesame Street floor director had to use the code phrase “blue skies, everyone!” to indicate “children on the set now, watch your language.”)

He was also far more interested in television production and experimental film-making than puppetry, per se. He got into puppetry because it was an opportunity to get onto local TV in the 1950s, and for years he used the Muppets to pay the bills while he continued to experiment in other areas of film and broadcasting. He was refreshingly non-precious in his attitude toward the puppets he performed. Carroll Spinney (who performs Big Bird) remembers the first day of Sesame Street filming, and being shocked when Henson casually tossed his Ernie puppet across the back of a chair and left for his lunch break. They were just tools of the trade to him, nothing to get sentimental over. (The puppet cast of his first TV show, Sam and Friends, spent a few years in his kids’ toy box before ending up as dishrags.)

He also may have been too creative for his own good. He got bored easily and tended to leap from project to project. He was more interested in getting things going than sticking with them. He spent the better part of a decade convincing people a concept like The Muppet Show would work. By the time he actually pulled it off, the four years in which he actually had to produce The Muppet Show felt like an absolute eternity to him. In the last few years of his life, he was often involved in a half-dozen projects at a time, several of which did not come to fruition, or ended up being disappointing in other ways because he simply did not have the time to give each one his full attention.

Finally, the death of Jim Henson is one of the most misunderstood parts of his legacy. Word circulated that he refused treatment due to his Christian Scientist beliefs. In reality, Henson’s mother was a Christian Scientist, and he followed its practices as a child, but as an adult, Henson adhered to no particular faith — his personal beliefs were undefined, but definitely came down on the yoga-granola side of New Age. He had nothing against medical treatment, but like a lot of people, he was reluctant to take time out of his schedule to see a doctor. He was rarely sick. When illness occasionally came along, he wrote it off as just overwork or a bad cold, and it was no big deal. Unfortunately, the relatively rare Streptococcus pyogenes infection which he contracted in May of 1990 is a big deal, and feels an awful lot like the flu until it’s too late.

The book’s graphic description of his final hours (total organ failure caused by a virulent bacterial infection is a rough way to go, kid), coupled with the amazing, incredibly touching Muppet-studded memorial service held not long after his death surprised me into tears — the first time a biography has moved me that much since Sperber & Lax’s Bogart.

BOOK OF THE YEAR:

Tune In: The Beatles: All These Years — Vol. 1 by Mark Lewisohn

Why another Beatles book? Because this is it — the definitive, final statement. Wait, wasn’t 2000’s massive Anthology book (based on the equally massive 1995 documentary) the definitive, final statement? No, because it was told by the Beatles themselves, and their recollections are notoriously hazy and often downright inaccurate, despite (or because of) being at the center of it all. Well then, wasn’t Bob Spitz’s 2005 band biography the definitive final statement? No. It was excellent for what it was, but it was a measly one volume…and Bob Spitz is not Mark Lewisohn.

For years, Mark Lewisohn has been known as the “Beatle Brain of Britain,” devoting his entire life and considerable scholarship skills to the world’s greatest band. He first meticulously cataloged all of their live performances in The Beatles Live (1986; the Holy Bee got it for Christmas that year), then even more impressively, their studio sessions, right down to the take numbers, mixes, and edits in The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions (originally published 1988; the Holy Bee got it for his birthday that year), and assisted in assembling Anthology. Now he has taken on the task of telling their whole story…in as detailed a fashion as possible. The colon-happy Tune In: The Beatles: All These Years is the first of a proposed trilogy. At 944 pages, it begins with their family ancestries and ends on December 31, 1962, when they were still local Liverpool favorites and not yet world-famous.

I assume most of you have grasped the fact by now that this is not for the casual reader.

If you’re a Beatles fanatic, however, you must read this book, which was a decade in the making. Lewisohn does not do a lot of de-mythologizing — the commonly accepted Beatles story, that so many of us know like our own family history, is pretty much true. Only a few minor misconceptions are left to clear up, and Lewisohn is just the person to do so. (For example, Stuart Sutcliffe eventually developed into a passable bassist before he left, the Lennon/McCartney team may have began songwriting as teen prodigies in 1957, but gave it up for almost five years, returning to it only on the cusp of fame, and their being signed by George Martin for EMI wasn’t quite as serendipitous as it first appeared…)

It’s the story of a band developing in the peculiar and insular culture of post-war Britain, a group of teenagers who everyone agreed were indifferent instrumentalists (at first), but always had a very special vocal quality, and extremely forceful personalities. The amatuer band went abroad and turned into hardened professionals through playing thousands of hours in the nightclubs of Hamburg, Germany. They became human jukeboxes clad in Gene Vincent-inspired black motorcycle leathers, churning out the radio hits of the day, obscurities, show tunes, country & western, rhythm & blues, and maybe slipping in an original composition or two by ‘62.

They were also driven by an ambition bordering on ruthlessness, turning their backs on or stepping over those who had worn out their usefulness. This was epitomized by the darkest stain on their early years: the firing of original drummer Pete Best. Some sources say he wasn’t good enough musically, others say he was no worse than any other “beat group” drummer of the era and the rest of the group were jealous of the attention he got from female fans, still others say his dour, quiet personality just didn’t mesh with the quick-witted loudmouths holding the guitars. Whatever the case, they wanted him out and Ringo in. They knew what they were going to do for months and gave no hint to Best, but made their new manager, Brian Epstein, call him into a meeting without the others and tell him he was dumped after two years on the drumstool. No one in the group ever spoke to him again, and have since sheepishly admitted it was an awful way to handle the situation.

(Lewisohn’s conclusion? Best was indeed a lousy drummer, and an impediment to their future success. The Holy Bee is no drumming expert, but on the handful of pre-Ringo recordings available, he certainly sounds like a weak link, pitter-pattering on the snare like a hamster on a cookie sheet, audibly speeding up and slowing down.)

Lewisohn actually moved to Liverpool for several years, rummaging around in city archives and amongst old newspaper clippings, using sources that have never been used by Beatles scholars before. He interviewed people who knew and worked with them in the early years who had never been interviewed before. The only thing missing is new interviews with McCartney and Starr, but they’re not the most reliable interviewees to begin with, and he’s interviewed them (and Harrison) many times over the years for other projects. The level of detail is mind-blowing. An example: Beatles fans know manager Brian Epstein, upon taking them on as clients, felt a more professional appearance would allow them to climb the show-business ladder. He insisted on sharp-looking suits and ties for all appearances. Lewisohn has not only tracked down the still-living tailor who custom-designed them their first suits (dark-blue mohair with extremely narrow lapels, single-breasted, three-button, with shirts, ties, collar pins and cufflinks, all for 23 guineas) and gives the date on which they got them (March 6, 1962), he goes on to describe how they carried them home (tartan suit bags with red handles.) That’s the sort of detail that comes up all the time in All These Years, and I loved wallowing in it for the full month it took me to read.

Volume 1 of All These Years (or is it Volume 1 of Tune In? It’s not clear what the overall title of the work is) leaves us with the Beatles on the cusp of celebrity, their first single (“Love Me Do”) in the Top 20 of the British charts, and their second (“Please Please Me”) already recorded and chambered like a bullet that would send them to Number One early in the new year of 1963. I don’t know how long the wait is going to be before Volume 2 comes out, which Lewisohn says will go to roughly the end of their touring era (August 1966), but he hints it will be several years at least.

Volume 1 of All These Years (or is it Volume 1 of Tune In? It’s not clear what the overall title of the work is) leaves us with the Beatles on the cusp of celebrity, their first single (“Love Me Do”) in the Top 20 of the British charts, and their second (“Please Please Me”) already recorded and chambered like a bullet that would send them to Number One early in the new year of 1963. I don’t know how long the wait is going to be before Volume 2 comes out, which Lewisohn says will go to roughly the end of their touring era (August 1966), but he hints it will be several years at least.

Addendum: There’s an expanded two-volume edition of “Volume 1” (pictured) available on Amazon.co.uk. with thousands of words of additional text. About $130. Sorely tempting…[ED. NOTE — I bought it and read it in 2020. Worth it.]

A good reading year, all in all, with biography leading the way as it usually does with me. I don’t know why I’ve become such a collector of people’s life stories, and maybe my predilection prevents me from branching out into other genres, but it doesn’t look like I’ll stop anytime soon. The third volume of William Manchester’s epic Churchill biography, The Last Lion, is on my desk, and Michael Burlingame’s two-volume Lincoln: A Life is queued up on the Kindle.

Peace out, finks.

You hit the nail on the head with the review of Five Days At Memorial… If you hadn’t had posted that you read this book, I would have never known about it. I really liked the read !