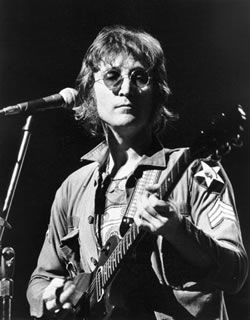

“Ringo liked films, but I think he just liked being in a Hollywood movie sort of world…he didn’t stop to say, ‘Hang on, I’m Ringo Starr. I have to choose carefully.’ He just did [the films] because they were good fun. Having a little laugh, you know? You get doomed for that, forever. People remember them.”

–Ray Connolly, That’ll Be The Day screenwriter

Ringo had a fairly successful follow-up album to 1973’s smash hit Ringo with 1974’s Goodnight Vienna. It reached a respectable #8 on the Billboard album chart, and its accompanying single “No No Song” got to #3 on the singles chart. But he couldn’t resist the allure of hanging out and having a little laugh on a film set.

It’s been so long since I left this website series hanging, I had to re-watch Lisztomania. The things I do…

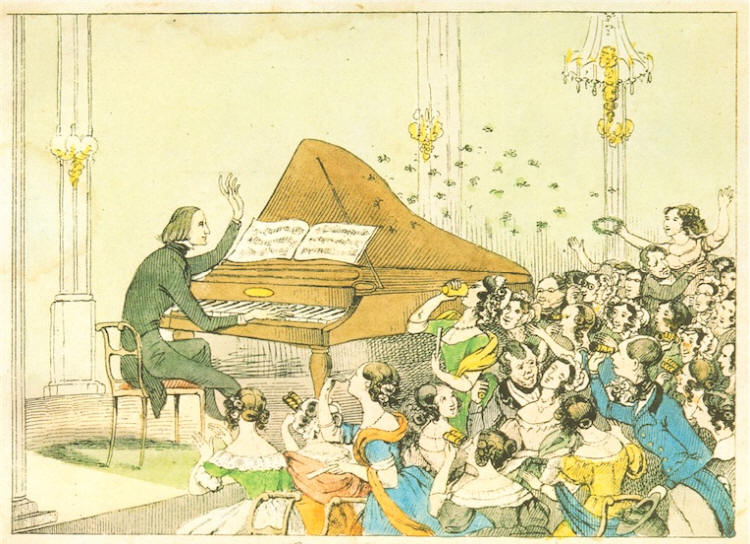

The term “Lisztomania” was coined by German writer Heinrich Heine to describe the effect composer and pianist Franz Liszt (1811-1886) had on an audience — mostly an audience of women. They would leap to their feet, scream, and sometimes faint. Liszt would rile them up, pounding out aggressive arpeggios, tossing his sweat-soaked hair, and distributing tokens such as scarves and gloves into the ecstatic crowd. It was the exact same effect that would crop up over a hundred years later in response to Elvis Presely and the Beatles.

Franz Liszt was the first rock star.

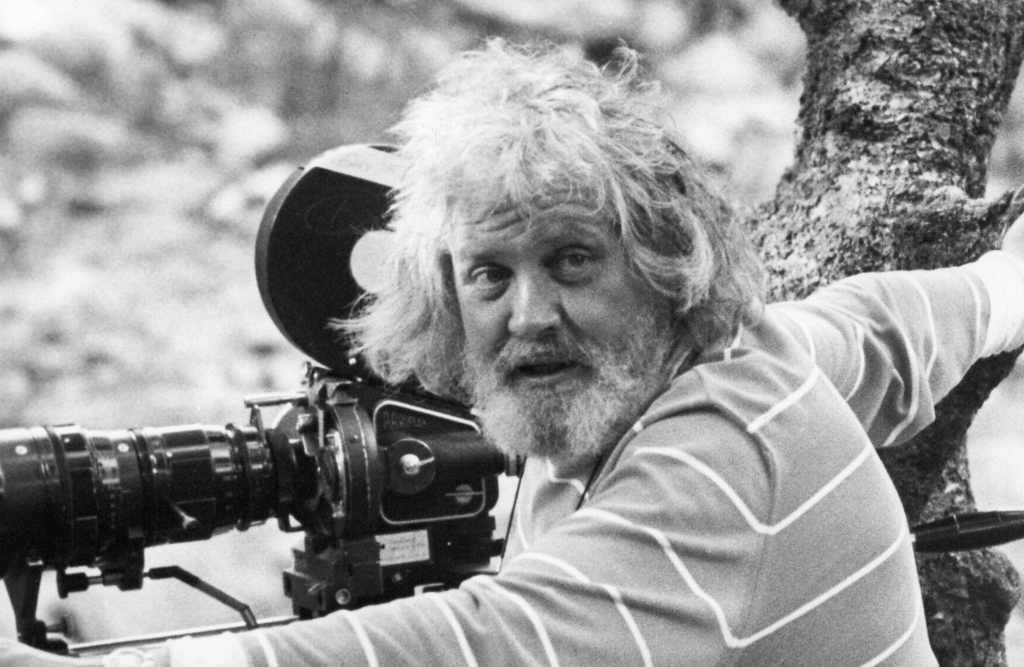

Director Ken Russell spun that single idea into a film that was as tedious as it was tawdry, its incoherence masquerading as “surrealism.”

But that’s Ken Russell for you.

“Lisztomania” cartoon by Adolf Brennglas, 1842

Franz Liszt was born in Hungary (thanks to some later border shifts, the town of his birth is now in Austria) and was considered a child prodigy. He studied under Antonio Salieri (yes, the Amadeus guy) and was said to have impressed both Beethoven and Schubert when he made his performing debut in Vienna at age 11. He subsequently lived for many years in Paris, composing, performing, and tutoring. He became personal friends (or sometimes “frenemies”) with fellow composers Felix Mendelssohn, Robert Schumann, Frederic Chopin, and most notably, Richard Wagner.

As he grew to adulthood, his chiseled features and flowing locks earned him many female admirers, but his reputation as a rabid womanizer was probably a little exaggerated. He was something of a serial monogamist, engaging in safe, long-term affairs with titled women in arranged marriages to indifferent (read: probably homosexual) husbands. One of these relationships, with Comtesse Marie d’Agoult, produced three children in the 1830s — daughter Blandine, son Daniel, and daughter Cosima, who later married composers Hans von Bulow and Richard Wagner in quick succession.

The “Lisztomania” period made up only a small portion of Liszt’s remarkable life. For seven years (1841-1848), he barnstormed the concert halls of Europe as a traveling virtuoso, selling sex appeal as much as music. He then quit performing to focus on composition, publishing the first of his Hungarian Rhapsodies and Liebesträume (“Dreams of Love”) in the early 1850s. He became the court conductor and choirmaster in the city of Weimar, Germany, a very settled-down and respectable position.

Liszt finally decided to marry for the first time to Princess Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein — who was, as usual, already married to someone else. He and Princess Carolyne spent over a decade trying to get her marriage annulled, to no avail. Even a sympathetic audience with Pope Pius IX in 1860 did not yield positive results in the end.

Pius IX (1792-1878) is known to history as the longest-serving pontiff. His leadership of the Catholic Church spanned 32 years, from 1846 to his death in 1878. He was initially a progressive supporter of church reform, but radical events such as the Revolutions of 1848 turned him more conservative. He orchestrated the literal kidnapping of a Jewish boy on the basis that he had been secretly baptized by a servant. Edgardo Mortara lived under “papal protection” until adulthood, despite the desperate pleas of his parents. The story brought waves of outrage, and contributed to Pius IX’s loss of the Papal States (a region of central Italy which the Pope had ruled directly as a sovereign monarch since 756).

Liszt and the princess gave up their attempts at matrimony. Liszt decided to become a monk, joining the Third Order of Saint Francis. He received a tonsure, and became Abbe Liszt. He still composed on a small piano in his monastery quarters. After almost a decade of cloistered life, Liszt returned to the wider world and bounced between Rome, Weimar, and Budapest, teaching master classes in piano. He never fully recovered from a fall down a staircase in 1881, and died five years later at the age of 74.

All of this is thrown into a cinematic blender by Ken Russell, along with celestial rocket ships, Nazis, vampires, superhero costumes, Nietzsche references, rayguns, and a ten-foot penis. (Not for nothing was one of Russell’s biographies titled Phallic Frenzy: Ken Russell and His Films.) “My film isn’t biography,” said Russell in the understatement of the year. “It comes from the things I feel when I listen to the music of Wagner and Liszt and when I think about their lives.”

Ken Russell was an authentic English eccentric. Born in 1927, his childhood ambition was to be a ballet dancer. Rather than sell shoes in his emotionally abusive father’s shop, Russell opted for disastrous stints in the Royal Naval College and the British Merchant Navy. When he washed out of the latter, he reluctantly returned to the parental home. One day his mother and a friend came home early and discovered a teenaged Russell frolicking around the house in the nude to Stravinsky’s Rites of Spring. There were embarrassed faces all around, and an ultimatum — sell shoes or join the RAF. It was an easy choice.

After being discharged from the RAF in 1948, Russell decided to make his childhood dreams come true. He was actually accepted into the International Ballet School in South Kensington, mostly because he was one of the few male applicants. It didn’t take long for Russell to discover the flaw in his dream — he was a terrible ballet dancer. The Institute patiently kept him on for four years before they finally, and no doubt with a certain degree of exasperation, asked him to leave.

After making ends meet as a freelance photographer and a bit player in touring musical comedies, Russell was hired by the BBC to work in their documentary department based on a few independent short films he had made. One of his early assignments was a documentary on the composer Sergei Prokofiev.

The BBC had a very strict policy regarding documentaries. No actors, no “dramatic re-enactments.” It was to be only narration played over authentic photos, talking-head interviews with experts in the field, and, if available, archival footage. The iconoclastic Russell kicked against this policy from the get-go, and went ahead and inserted brief bits recreated by actors — hands on a keyboard, a reflection in a pond, that sort of thing. Despite admonishment from the BBC suits, he took it even further with his next composer biography on Edward Elgar. This was the beginning of a leitmotif in Russell’s career — a series of biographical films on composers. From relatively staid documentary works for BBC arts shows like Omnibus and Monitor in the 1960s to the twisted, overbaked cinematic explosions of the 1970s, Russell always returned to presenting the lives of composers.

Russell made his big cinematic breakthrough with an acclaimed adaptation of D.H. Lawrence’s Women in Love in 1969. Conventional compared to his later works, Women in Love still broke boundaries, featuring the first full frontal male nudity in a mainstream film. The naked wrestling match between Alan Bates and Oliver Reed certainly got the film a lot of attention…and repeat viewing. His next two composer biographies, The Music Lovers (1971) about Tchaikovsky, and Mahler (1974) reflected Russell’s increasing self-indulgence and reliance on surrealism. “More interested in impressionistic history than literal truths,” is how Russell biographer Joseph Lanza generously put it.

Russell’s flamboyant, overblown style was already familiar enough to be parodied by Monty Python in 1972.

To be fair, Russell always did meticulous research and did throw in small nuggets of historical accuracy as long as they were suitably weird. For example, Princess Carolyne really did smoke cigars and really did write a 24-volume work entitled The Inward Reasons for the Church’s Outward Weaknesses as depicted in Lisztomania.

Mahler was the first of a proposed six-film series on composers to be written and directed by Russell and produced by David Puttnam’s company Goodtimes Enterprises. It was to be followed by a film about Franz Liszt, for which Russell initially envisioned Mick Jagger as the star.

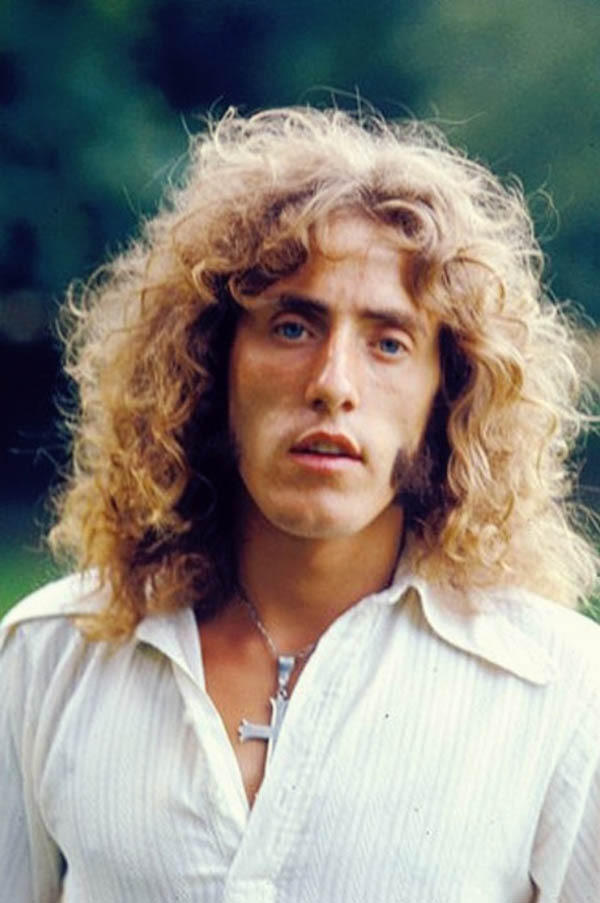

Before he jumped into the Liszt biopic, Russell decided he wanted to adapt the Who’s “rock opera” Tommy. The work was first released by the Who as a concept album in 1969, and performed by them as a three-piece band in opera halls as well as the usual rock venues across Europe and America. Classical music purist Russell was no fan of rock, but hearing the London Symphony Orchestra perform the Tommy material in true classical style in 1972 piqued his interest. He got in touch with Who guitarist/songwriter Pete Townshend, and the two hit it off and agreed to collaborate. It seemed only natural to cast Who lead singer Roger Daltrey as the title character. Tommy (1975) was a critical and box-office success, although I suspect the Who’s music and appearances by Elton John, Tina Turner, and Eric Clapton were more of a draw than Russell’s typical high-camp hallucinatory style.

At some point during the production of Tommy, Russell made a mental switch from Jagger to Daltrey for the role of Franz Liszt, and announced him as the lead in what was now called Lisztomania a month after Tommy had wrapped. Russell felt that Lisztomania would be a true companion piece to Tommy, exploring similar themes.

Continue reading