Dateline: Davis, CA. COVID-19 “shelter-in-place” quarantine, March 18 through…?, 2020

A patched-together overview of some of my Spotify artists’ playlists in roughly alphabetical order…

It was some time around the tail-end of the holidays, 1995. We (that is myself, WH, and our mutual friend Allen) were on one of our many record shopping excursions in Sacramento. Our route always began out in suburbia with Tower Records on Watt Avenue, then we worked our way into the city center by way of The Beat on J Street, and we usually ended up on K Street in the heart of downtown. Like many hearts of many downtowns, Sacramento’s K Street has faced the usual challenges of street crime and homelessness. It may have been at its lowest point on that cold, gray day as ‘95 changed over to ‘96. Someone in an army overcoat was loudly telling sinners to repent on the corner of 7th and K, and the scent of fortified wine and urine was in the air as we walked by huddled, sleeping figures, and slipped through the seedy doorway of 708 K Street. A former saloon, the address still boasted a flophouse hotel on its upper floors.

The old K Street Records building as it appeared in 2011. It now has a new facade as part of the K Street renovation project.

But its ground floor was home to K Street Records, one of the most gloriously disorganized and haphazard retail establishments I have ever had the pleasure to peruse. Stacks of vinyl lined the walls with no rhyme or reason, and even the supposedly alphabetized bins of CDs were a crapshoot. To make up for it, a very friendly mottle-coated cat offered an almost deafening purr in exchange for an ear-scratch, which may have been the best deal in the place. Nick Cave was playing on the store’s sound system that day.

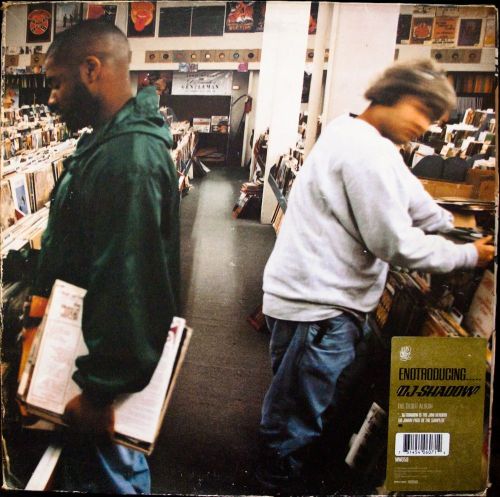

Even more stock was available down in the basement, but I don’t recall ever going down there. It may have been closed to the public entirely at that point. Local legend states the basement of K Street Records was haunted by the spirit of a lady (“Gertrude,” I’m told) in a Victorian dress who could be a tad hostile. The establishment is also semi-famous for being on the cover of DJ Shadow’s breakthrough sample-fest Endtroducing…, a photograph taken not long after this day’s visit. One has to assume a lot of the vintage vinyl that comprised the Davis native’s debut album came from K Street.

DJ Shadow’s Endtroducing… album cover, 1996

We didn’t find anything at K Street Records, so we moved on down the block to another Tower Records. The K Street Tower Records was the venerable chain’s third Sacramento location (after the Watt Avenue and Broadway stores, both dating from the ‘60s), which opened in 1973. The entryway was decorated with a massive, funky, very ‘73 mural.

Former entrance to the K Street Tower Records, c. 2011, where the Holy Bee was drafted into the Britpop Wars back in ’95. The foyer floor still believes it’s the 1950s and “Burt’s Shoes” is the proper occupant.

We weren’t there long before WH waved me over. “Come here.”

I did so.

“Hold out your hand.”

I did so.

He dropped two brand-new, shrink-wrapped CDs into my open palm.

“Buy these today. Thank me tomorrow.”

That’s how I came to buy Oasis’ 1994 debut Definitely Maybe and their new release (What’s The Story) Morning Glory. And WH was right. I had no regrets. Oasis rocketed to the top of My Favorite Bands list before Definitely Maybe was halfway over. (My other purchase from that day, Southern Culture on the Skids’ Dirt Track Date, ended up getting sold off within a few months.)

Oasis’ formula was simple: Build a song solely around its best parts — the big riff and the catchy chorus — and repeat them as loud as you can. It’s really not much different from AC/DC’s approach, but Oasis added just a splash of Beatles/Kinks melodicism. I derived immeasurable joy out of those first two Oasis albums. My white Dodge Colt (with the black left front fender) soon boasted an Oasis sticker in the back window. They were all I wanted to listen to in the first few months of ‘96 (well, them and Tom Waits, and the Pogues — see below — but I was never able to find a good Pogues sticker for the car).

[Sacramento’s K Street has been undergoing renovation and renewal for several years now, aided by the development of the adjacent Golden 1 Center basketball arena. The old K Street Records building now houses the stationary bike gym All City Riders. The Tower Records mural has been painstakingly restored, and the space is now occupied by Solomon’s Deli, named after Tower Records founder Russ Solomon. Unfortunately, the pandemic shut-down has hit K Street businesses pretty hard.]

Tower Records K Street reborn as Solomon’s Delicatessen, 2018.

The “Britpop Wars” broke out around this time. It was Oasis (simple, working-class) versus Blur (nuanced, middle-class). It was the noisy pub versus the quiet university common room, and each band’s fanbase was very opinionated. Naturally, I was in the Oasis camp, and had many spirited debates at the local coffee shop with the snobbish and pretentious Blur crowd. In retrospect, Oasis and Blur weren’t really all that different.

The true polar opposite to Oasis — musically, philosophically — is Radiohead.

Radiohead — more fun than a barrel of monkeys

I am dedicating the next portion of these Chronicles to a band that will probably not be getting a playlist. For a little over fifteen years now, I have declared Radiohead to be absolutely, without a doubt, the most overrated band in popular music history. But it’s been awhile since I voluntarily listened to them. Now it’s time to see if I need to eat my words. I have announced to certain members of the Idle Time collective, who never fail to quiver like jelly and sigh in ecstasy whenever Radiohead’s name is mentioned, that I would use some of my quarantine time this past summer to clear my mind of prejudices and preconceived notions, and listen to each and every album in the Radiohead catalog as if I’m hearing them for the first time (which, in the case of their last two albums, is literally true).

Here we go.

Pablo Honey (1993)

Radiohead’s debut album is the one most likely to be dismissed as sub-par (especially by the band themselves). I thought it was pretty good, although the oppressive sulkiness of the lyrics precludes me from saying I “enjoyed” it. The production team of Paul Kolderie and Sean Slade were chosen for their work with the Pixies and Dinosaur Jr. and it shows. The quiet/loud/quiet dynamic of the Pixies (also used by Nirvana to great effect) and guitar crunch of Dinosaur Jr. are the dominant modes of Pablo Honey. The band were still clearly wearing their early influences on their sleeve. In addition to the aforementioned acts, there is a very healthy dose of early U2 all over the place, particularly in Thom Yorke’s Bono-channeling vocal gymnastics.

Radiohead’s debut album is the one most likely to be dismissed as sub-par (especially by the band themselves). I thought it was pretty good, although the oppressive sulkiness of the lyrics precludes me from saying I “enjoyed” it. The production team of Paul Kolderie and Sean Slade were chosen for their work with the Pixies and Dinosaur Jr. and it shows. The quiet/loud/quiet dynamic of the Pixies (also used by Nirvana to great effect) and guitar crunch of Dinosaur Jr. are the dominant modes of Pablo Honey. The band were still clearly wearing their early influences on their sleeve. In addition to the aforementioned acts, there is a very healthy dose of early U2 all over the place, particularly in Thom Yorke’s Bono-channeling vocal gymnastics.

Ironically, as later releases would downplay the dominance of the six-stringed instrument, Pablo Honey may be one of the best “guitar albums” of the 1990s. Clear, ringing chords and arpeggios reminiscent of the Smiths or XTC are neatly interwoven with the fuzzed-out distortion of grunge — causing the album to be (unfairly, in my opinion) lumped in with the many other grunge knock-offs in the post-Nirvana world of 1992-93. (Remember, early Radiohead weren’t copying Nirvana, they were copying the bands Nirvana copied. There’s a difference.) What sets Pablo Honey apart from the more pedestrian knock-offs were the little sonic surprises that littered the first half, such as the stately piano that wanders into the last few seconds of “Creep,” the massive hit single that made the band instant stars and MTV darlings, and the song the band has worn like a millstone around their necks ever since.

Pablo Honey’s music itself is often quite sprightly, even though the lyrics wallow in alienation and self-pity, always warning the perpetrators of their torment that some kind of personal or spiritual retribution is coming. At times they sound like Material Issue’s depressed, vindictive British cousins. The album does suffer from second-half fatigue. (Certainly not the only album guilty of this — many artists and their production teams beginning in the CD era felt it was best to front-load albums with the strongest stuff to keep short attention spans from punching the skip button too early.) As the album winds down, it gives us a run of mid-tempo odes to self-loathing that blend into each other with little to distinguish them. The closer, “Blow Out,” has a nice, hushed urgency, and reminds me a little of Television. Overall verdict: A solid, but at times gloomy and derivative, debut with a great guitar sound that elevates it slightly above its post-grunge peers.

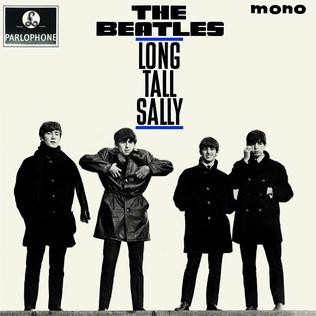

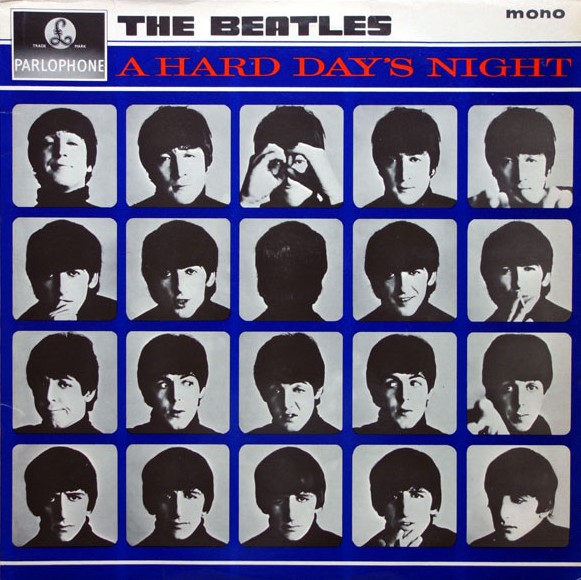

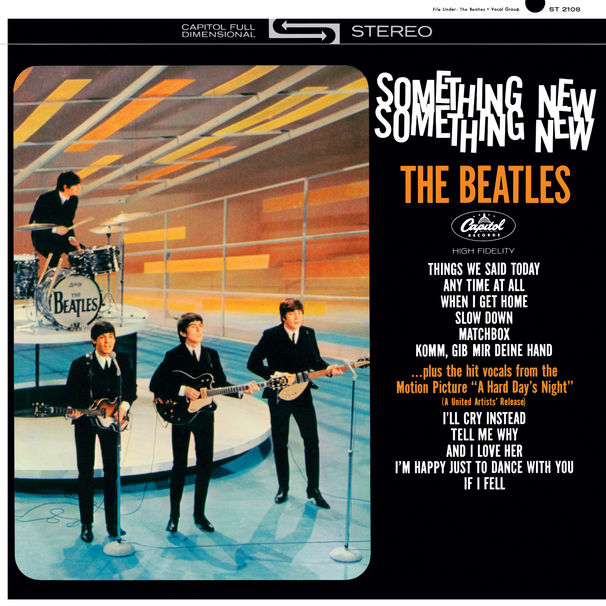

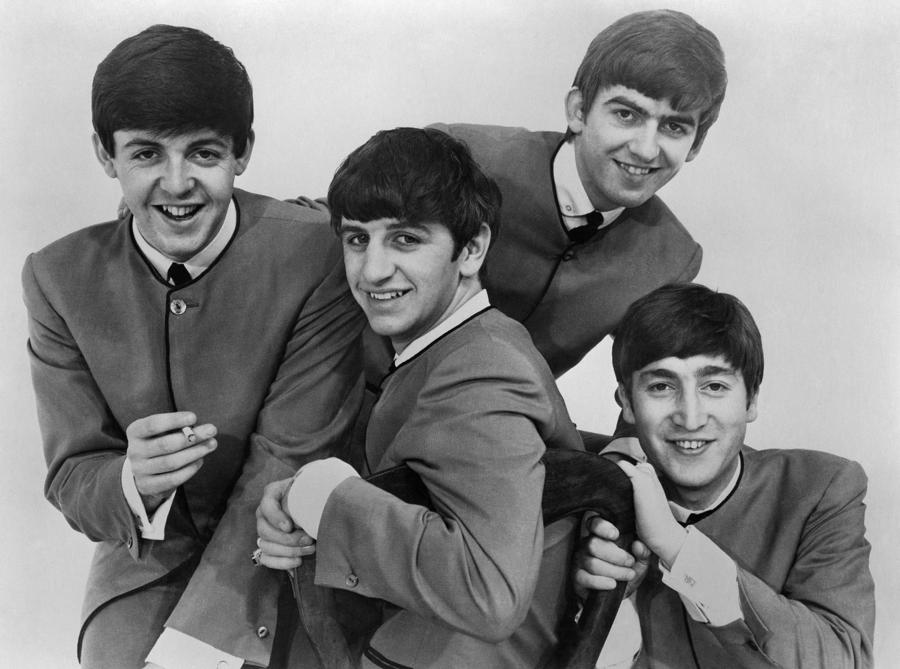

the demand for new Beatles product by expanding the potential “Long Tall Sally” single into an EP — an “extended play” four-song 45-rpm, a format that was quite popular in Britain but never caught on in the States.

the demand for new Beatles product by expanding the potential “Long Tall Sally” single into an EP — an “extended play” four-song 45-rpm, a format that was quite popular in Britain but never caught on in the States.

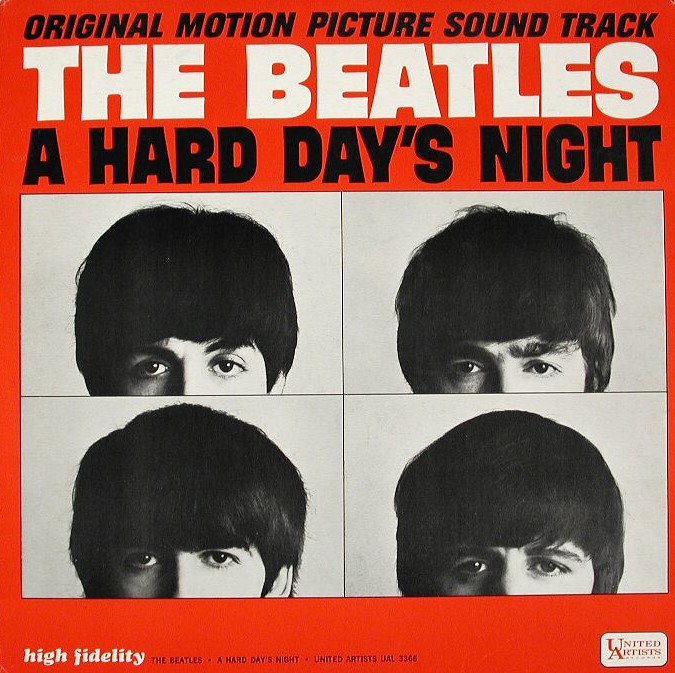

album on July 10, 1964, with the following track list:

album on July 10, 1964, with the following track list:

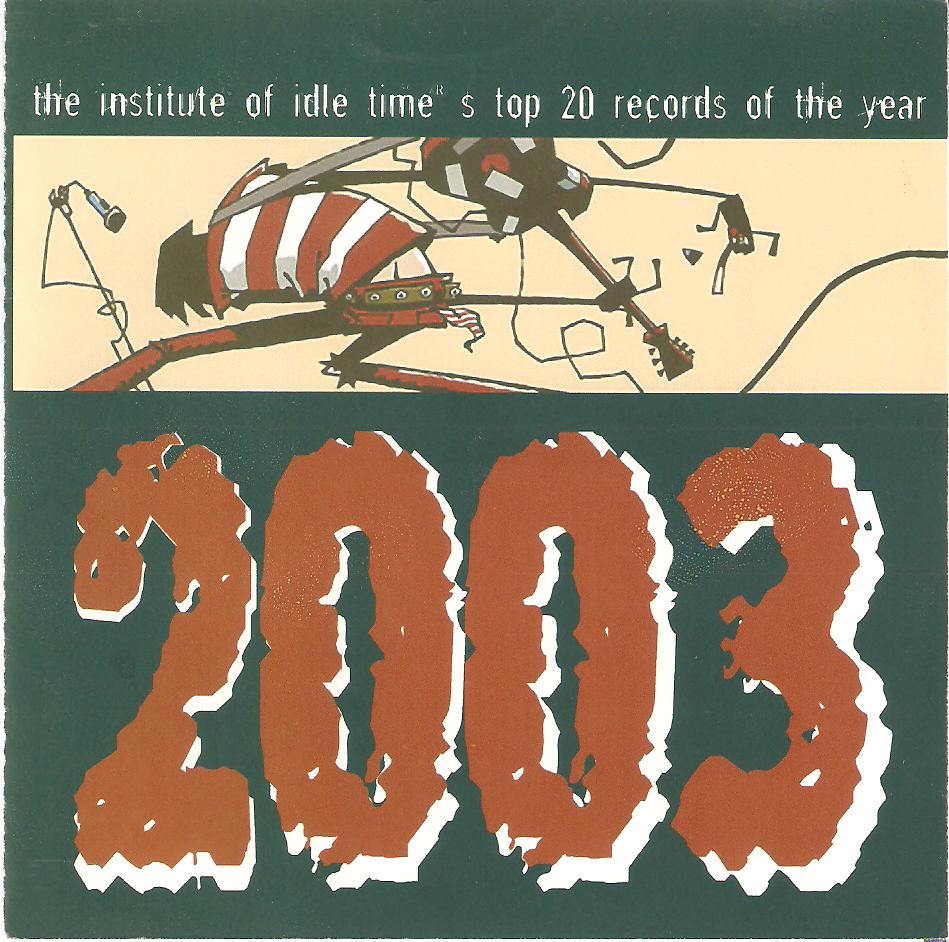

I co-founded the

I co-founded the  We went from friends, happy to find common ground in something like 02’s

We went from friends, happy to find common ground in something like 02’s  Membership expanded and became fluid — different members have come and gone over the years (including myself, as we’ll see), but it always seems to hover around ten.

Membership expanded and became fluid — different members have come and gone over the years (including myself, as we’ll see), but it always seems to hover around ten.

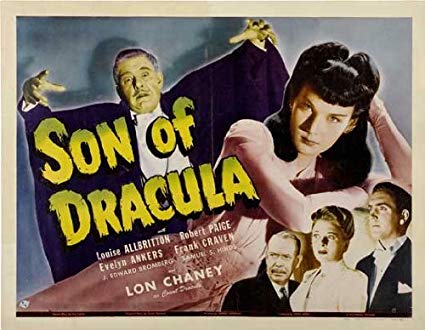

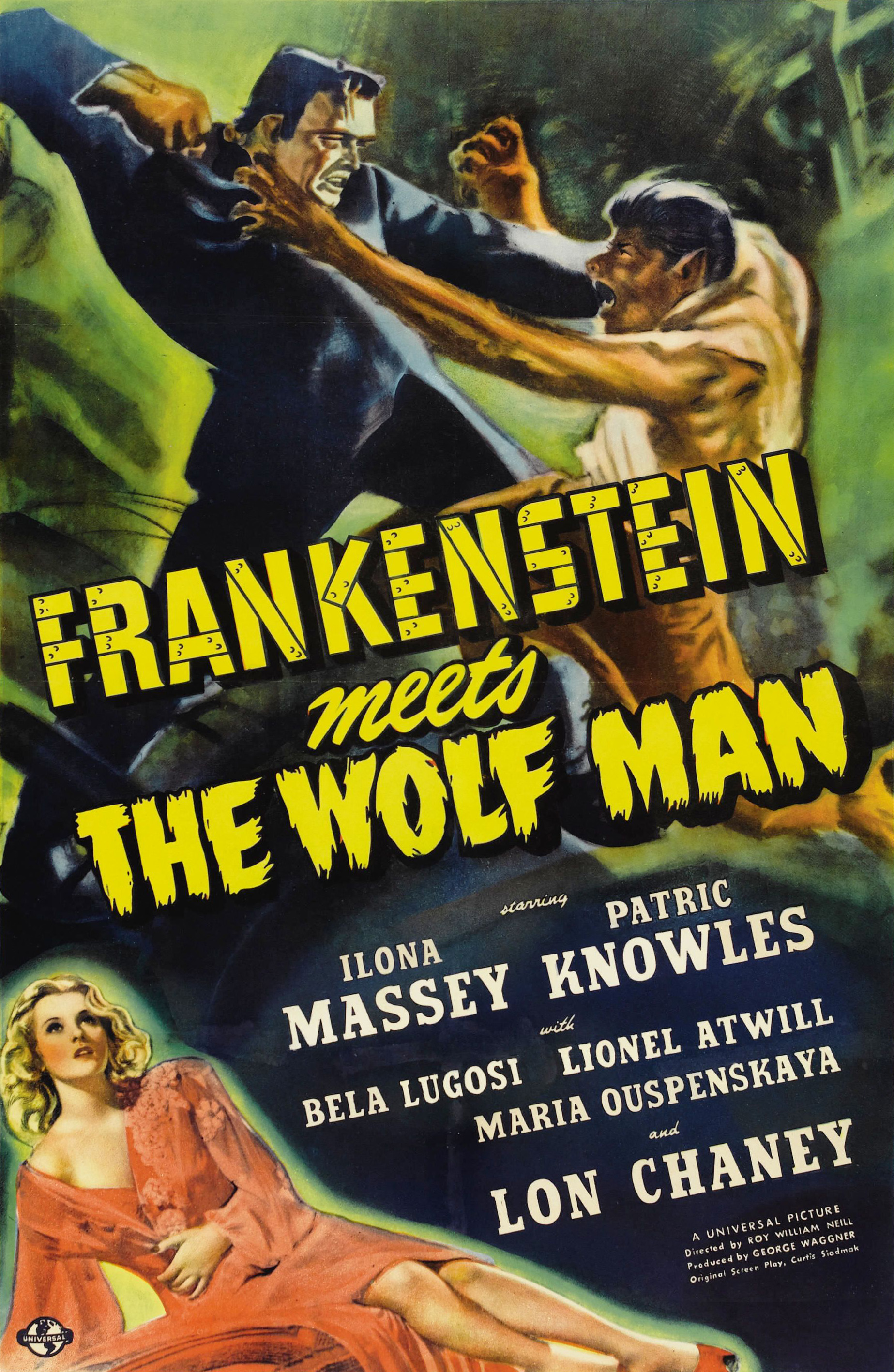

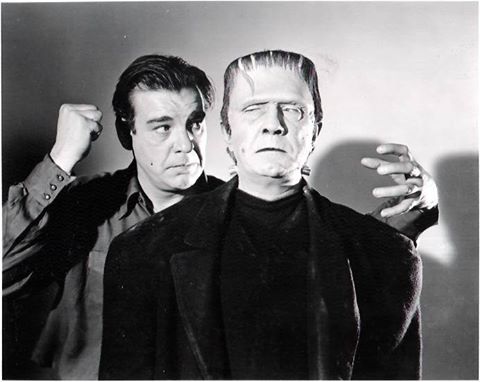

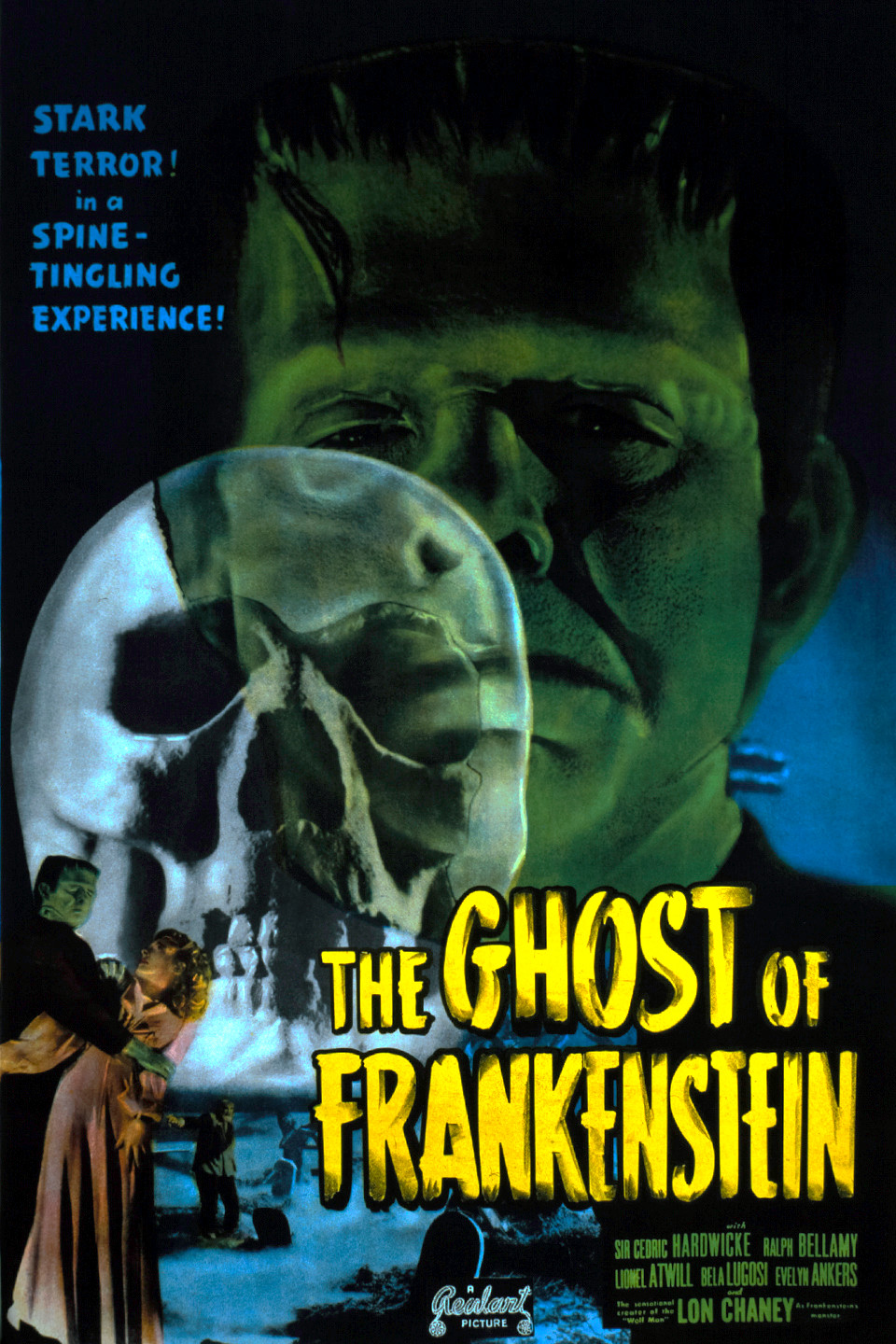

The Ghost of Frankenstein

The Ghost of Frankenstein