Soon(ish)…

Quiescence

Filed under Life & Other Distractions

Act Naturally: The Films of the Solo Beatles (Part 3)

Imagine if a musician chose the discordant throwaway “Only A Northern Song” as the pinnacle of the Beatles’ output, and used it as a template for the entire sonic palette of their own work for years. You’d probably get a musician very similar to Frank Zappa. (In reality, Zappa’s approach was a combination of his affinity for ‘50s R&B combined with modernist composers like Edgard Varese, but the results were more or less the same.)

Frank Zappa

I never much liked Frank Zappa. I suppose there’s a twisted appeal to listening to someone using immense talent for the purposes of coming off as a second-rate novelty act, but I don’t get it. His general approach, at least on his rock albums with his backing band, the Mothers of Invention, is to combine heavy-handed social satire with an incredibly sophomoric sense of humor. (His work in modern classical and jazz is beyond my scope to comment on.) The best parody/pastiche comes from having an affection for the original material, and Zappa always came off as contemptuous of ‘60s rock. In fact, “arrogant contempt” seems to be his default mode for most things, and that’s one of the reasons his humor falls flat.

Admittedly, Zappa’s arrangements were tight. The musicians he assembled could always hold down a solid groove, and his guitar playing was often incendiary, but the material was undercut by the jokey vocals, dumb spoken-word monologues, sub-Spike Jones sound effects, and inane lyrics that veered between juvenile sex jokes, scatology, and pretensions of cultural relevance. Many of the “tracks” on his albums are useless little fragments. If you want to sit through twenty-six seconds of whispering and backwards tapes titled “Hot Poop,” more power to you. I’ll pass. (Yes, I know in this context “poop” means “gossip,” but don’t tell me the writer of “Don’t Eat the Yellow Snow” wasn’t aware of the double meaning.)

The magic of the Beatles is their timelessness. Rob Sheffield explored this quality in his book Dreaming the Beatles (highly recommended), pointing out that for a long time, the Beatles themselves failed to grasp the immensity of their continuing appeal. Before their deaths, both Lennon and Harrison were frequently puzzled and annoyed that people refused to let the whole Beatles thing go. They waved it off as nostalgia. Well, you can’t be nostalgic for an era you never witnessed, and I’d wager millions of current hardcore Beatles fanatics were born after 1970. By now, Paul seems to get this. (Bless his heart, but peace-and-love-peace-and-love Ringo still seems to be pitching his endless stream of new albums and tours to a rapidly dying-off Boomer audience.) Frank Zappa is the opposite. He is so firmly of his time it’s as if he were preserved in amber. For years, Zappa remained locked in a greasy, confrontational “1968,” flying his increasingly pointless freak flag, and trying desperately to shock the “squares.” And when he finally updated his style, he decided to poke fun at disco and Valley girls, true Statements for the Ages.

Zappa and his legion of fans would probably say I’m missing the point. And maybe I am. And if someone gave me the choice between listening to Zappa or the Grateful Dead for an afternoon, give me Zappa every time. At least I wouldn’t be falling asleep listening to an alleged “song” featuring Jerry Garcia elaborately playing scales for 25 minutes.

The kicker to all this? The Beatles loved Frank Zappa.

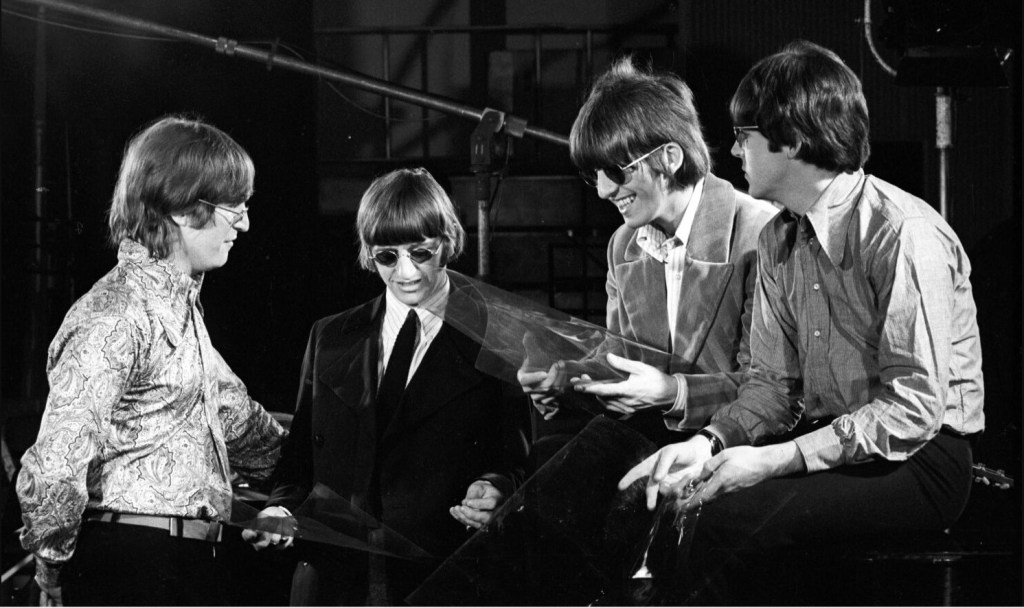

Paul was overheard on the Sgt. Pepper session tapes proudly saying “This is our Freak Out!” (a reference to Zappa’s 1966 debut album). One of the handful of times John played live during his solo years is when he joined Zappa onstage at the Fillmore East in June of 1971. And Ringo took a role in Zappa’s 1971 film 200 Motels.

200 MOTELS

Released: October 29, 1971 (L.A.), November 10, 1971 (N.Y.)

Director: Frank Zappa, Tony Palmer

Producer: Herb Cohen, Jerry D. Good

Screenwriter: Frank Zappa, Tony Palmer

Studio: United Artists

Cast: Theodore Bikel, The Mothers (Mark Volman, Howard Kaylan, Aynsley Dunbar, George Duke, Ian Underwood, Martin Lickert, Jim Pons), Ringo Starr, Jimmy Carl Black, Don Preston, “Motorhead” Sherwood, Janet Neville-Ferguson, Lucy Offerall, Pamela Des Barres, Ruth Underwood, Keith Moon, Dick Barber, Judy Gridley

Zappa had always dabbled in filmmaking. His short film, Burnt Weeny Sandwich, was aired on KQED in San Francisco in 1969, and he was constantly tinkering with his multi-media Uncle Meat project (the film portion of which would never be officially completed). His idea for 200 Motels — how life on the road as a touring band could drive you crazy — stemmed from the Mothers of Inventions’ very first tour in 1966. The vaunted Zappa originality would lie not in the premise (which was pretty trite even back then), but in the execution. He pieced together a score in bits and pieces over three years, and arranged to have it performed at UCLA’s Pauley Pavilion.

As an orchestral piece, 200 Motels had its debut performance on May 15, 1970, conducted by Zubin Mehta. The 96-piece Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra joined forces with Zappa’s nine-piece rock band in an acoustical and technical trainwreck. But the audacity was admired. The initial idea was to expand 200 Motels into a TV special for Dutch television. When Zappa brought in British director Tony Palmer to consult, Palmer demonstrated his pioneering video-to-35mm film transfer system which he’d used on his film of Cream’s farewell concert in 1968. Zappa decided to turn the project to a feature film, knowing that by using video he could shoot and edit quickly, and keep costs down.

In November 1970, Zappa was about to leave on a European tour with an all-new Mothers band (the “of Invention” was mostly dropped, and they now featured former Turtles Mark Volman and Howard Kaylan on vocals). Just before his departure, he met with United Artists chief David Picker to arrange a film deal for 200 Motels. Based on thirty minutes of music, a ten-page treatment, and a few photos, United Artists agreed to fund the film in exchange for rights to the soundtrack album. Shepperton Studios just outside London was booked for early 1971. The European tour ended on December 17, and Zappa headed to England to get started on the project. Shepperton turned out to be unavailable due to Roman Polanski’s Macbeth running over schedule, so the production hastily shifted to another British studio, Pinewood.

Ringo Starr was at that time in the depths of Beatles Break-Up misery. On December 31, 1970 Paul officially sued the other three Beatles to dissolve the band’s business partnership, a regrettable but necessary move. No one wants to go through a lawsuit, but Paul — correctly — did not want his finances managed by the criminal sleazebag (Allen Klein) the other three had naively hitched their wagons to, and he wanted out. Sometime just before or just after the lawsuit was filed, the phone rang at Round Hill, Ringo’s Highgate mansion. “A call came from the Apple office that Frank Zappa had this idea, and he wanted to present it to me,” recalled Ringo. “So, I invited Frank to my house. He laid this huge score out and said ‘I’ve got an idea to make this movie, and here’s the score.’ I said, ‘Why are you showing me the score? I can’t read music. But because of that I will do the movie.’” [That’s the quote, but I’m still not sure because of what.]

Tony Palmer agreed to co-direct, utilizing his video-to-film technique. Much of 200 Motels would be performance pieces by the Mothers and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. The narrative segments would feature the Mothers (none of whom could really act, so they just improvised around Zappa’s written outlines), former Mothers, real-life groupies playing onscreen groupies, Ringo, and Who drummer Keith Moon (who, as we’ll see, pops up almost every time Ringo appears before a camera in anything). The lone professional hired for the project was veteran character actor Theodore Bikel.

Mothers bassist Jeff Simmons quit just before filming (or rather, taping) started, and an infuriated Zappa said he would give the part to the next person who walked in the room. The lucky winner was Ringo’s driver, Martin Lickert, who actually knew how to play bass guitar. Problem solved. (A weird story circulated that Zappa brought in Wilfrid Brambell — Paul’s “clean” grandfather from A Hard Day’s Night — put him in a long-haired wig and gave him a bass to hold. The near-elderly Brambell was completely bewildered and didn’t last long in the part.) Turtles bassist Jim Pons was also on hand, though his role was murky. (Both he and Lickert were officially credited as Mothers on the soundtrack album, and both did stints on tour with Zappa later in ’71.)

After six days’ rehearsal with the band and orchestra, shooting occurred from January 28 through February 5, 1971 on two Pinewood sound stages. Zappa directed the performers and played with the band, Elgar Howarth conducted the orchestra, and Palmer directed the four video cameras from a control center in an off-set truck. The music would be performed and recorded live on set, rather than the normal procedure of pre-taping and synching the soundtrack in post-production. Three of the orchestra members wanted nothing to do with the material, and quit after the first day’s rehearsal (maybe they shared a taxi home with Wilfred Brambell). The brief shots of the mostly middle-aged Royal Philharmonic members seen in the final film show them either as very uncomfortable, or as slightly bored-looking professionals getting through a gig they were booked for.

Although I used the term “narrative segments” in an earlier paragraph, there is no narrative as such. The whole thing takes place on a crappy, cardboard-looking set on an obvious sound stage (deliberately built to look like a crappy, cardboard-looking set on an obvious sound stage) representing “Centerville, USA” — a hellish limbo where the Mothers are stuck while on tour. There are some vague themes — the band waiting to get paid by the dictatorial Zappa, getting hassled by rednecks at the local diner, and an overall fixation on genetalia and groupies (both Zappa obsessions). But, really, no sense is to be made from any of it.

“Within the conceptual framework of this filmic event, nothing really matters,” says Rance Muhammitz. “It is entirely possible for several subjective realities to co-exist. It is possible that all things are a deception of the senses.”

“Right on, Rance,” agrees (former) band member Don Preston. “The functioning of our senses has been spiritually impaired and chemically corrupted by the fake artificial food coloring.”

That bit of dialogue comes in the first eight minutes, and serves as an attempt to excuse the ninety interminable minutes that follow.

Here’s what we’re treated to: A KKK meeting with all the members singing a song called “Penis Dimension.” Keith Moon in drag as “the Hot Nun” trying to be a groupie. An incredibly overlong animated sequence created solely to lambast departed bassist Jeff Simmons. The band members randomly wrestling someone in a vacuum cleaner costume. Fish/lizard people wandering around. Another “nun” in a suit made of cardboard boxes. Dance routines that challenge the definition of both “dance” and “routine.” Did I mention all the stuff about groupies? (Janet Neville-Ferguson performs a number called “Half A Dozen Provocative Squats” — topless, of course — and Pamela Des Barres has a small part as a “rock journalist” in a leather Nazi SS uniform. Zappa always treated symbolism as a sledgehammer.) The whole thing is very meta, with participants addressing the audience and the mostly off-camera Zappa, making inside jokes about other bands and musicians, and commenting on the film’s strangeness.

As stated, the Mothers played themselves. They were joined by several members of the original Mothers line-up, who had all been unceremoniously fired by Zappa back in 1969. No hard feelings, I guess. Original drummer Jimmy Carl Black gives the best “performance” in the film, both as his straightforward, laconic self and as the “Lonesome Cowboy Burt” character. Theodore Bikel as “Rance Muhammitz” serves as a kind of master of ceremonies through the whole thing, but 200 Motels resists all attempts at structure.

Zappa is only briefly glimpsed on screen during some of the performance sequences. Standing in for him in the other portions of the film is Ringo, playing “Larry the Dwarf,” who is in turn playing “Frank Zappa.” Ringo as “Larry/Frank” (“a very tall dwarf”) sports a Zappa wig and a big Zappa mustache. He pops up from time to time to be interviewed by Rance Muhammitz, or deliver some rambling monologues. Although anyone who’s read candid interviews with any of the Beatles knows their language can be as blunt and colorful as anyone else’s, it is a bit off-putting hearing our beloved Ringo talk explicitly about “fucking” and “scoring pussy.” But remember, he’s playing Frank Zappa. As in The Magic Christian, there is not much to be said regarding Ringo’s performance from a technical standpoint. Once again, he’s basically playing himself — dressed as Zappa. His well-known Liverpool accent is firmly in place. Zappa biographer Barry Miles reported that Ringo was suffering a heavy cold through the brief shoot, and read all of his lines off of cue cards. When Ringo wasn’t playing the role, his place was taken by a stuffed dummy with Zappa’s distinctive features drawn on it. The difference was negligible.

The musical portions are a migraine-inducing dumpster fire of zooms, frenetic edits, flashing lights, and jarring close-ups. The whole production, even the non-musical scenes, are completely slathered in cheesy video effects — solarization, double- and triple-exposures, and false colors. In the words of the Den of Geek website, the video effects are “overbearing, unrelenting, and incomprehensible.” The use of video instead of film as a shooting medium did the production no favors, except for maybe saving a few bucks at the time. The combination of shooting on video, low-tech effects, and the junky sets makes the whole thing look like the world’s most catastrophic 1970s PBS kids’ show. In 21st-century parlance, Zappa and company would say all of these are “features not bugs,” and the film’s look was absolutely intended. But it doesn’t make it any more watchable knowing Zappa wanted it that way.

A couple of typical shots from 200 Motels

Or did he?

Continue readingFiled under Film & TV

Act Naturally: The Films of the Solo Beatles (Part 2)

In post-WWII France, an unlikely friendship developed between two American students studying at the Sorbonne on the G.I. Bill — one a sad-eyed Texan with a taste for the darkly absurd, the other a voluble New York dilettante who fancied himself a poet. The Sorbonne had no set schedule of classes, just the requirement to defend your thesis, and attendance-optional lectures from the likes of Sartre, Camus, and Cocteau. That left the two young men plenty of free time to linger in Parisian coffee shops, cinemas, and jazz clubs.

Terry Southern and Mason Hoffenberg were the original platonic ideal of the insufferably pretentious hipster — shamelessly appropriating jazz lingo (“dig this, man”), and passing sneering judgment on the bourgeois and “square” while actually doing or producing very little themselves. Southern finally broke free of this mold and became a writer of some repute (and became self-aware enough to satirize his own hipsterism in several of his stories). Hoffenberg, however, went on to do next to nothing, except a shitload of heroin. He managed to latch on the entourages of various rock stars in the ‘60s and ‘70s as a kind of amusing junkie mascot. I challenge you to find anyone with a Wikipedia entry who has done less to earn it.

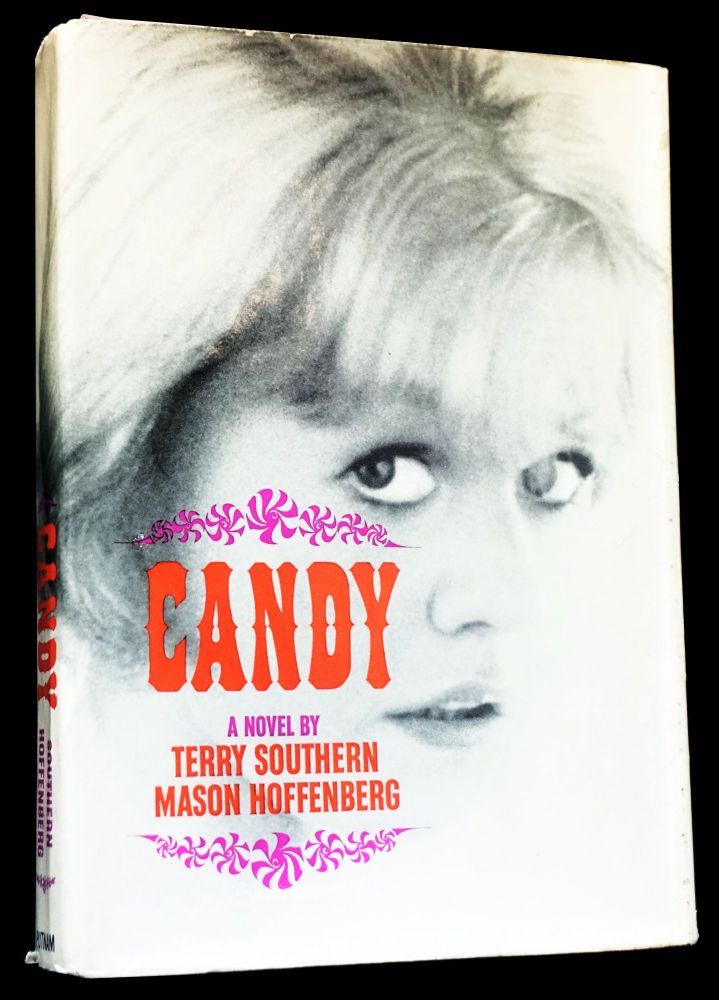

By the mid-1950s, Southern was scratching out a living in Geneva, Switzerland as a writer of increasingly surreal short stories, while Hoffenberg remained in Paris, writing erotic fiction under a pseudonym for the notorious Olympia Press. Some of Southern’s writing also skirted the boundaries of what was then considered acceptable, such as his unpublished (and pretty much unpublishable) story about a beautiful, naive college student named Candy Christian who, according to Southern, is “compassion incarnate…so filled with universal love that she gave herself fully and joyfully…to a demented hunchback.” Southern circulated the grotesque sex tale among his associates. He fleshed it out a bit at Hoffenberg’s suggestion, and it eventually captured the attention of Maurice Girodias, head of Olympia Press, who thought it might be a suitable product for what was then still called the “dirty book” market. It became a collaboration between Southern and Hoffenberg, who would exchange character details and plot points via mail. Even those generously disposed towards Hoffenberg have to admit that the original correspondence (which has been preserved) shows that he contributed very little that made its way into the finished work, and that it was mostly Southern’s prose that ended up being published by Olympia Press. (In the final version, it seems Hoffenberg contributed one character arc and the novel’s ludicrous last few pages — a “climax” not used in the film version.)

Candy was published in 1958 under the name “Maxwell Kenton,” and was promptly banned in both the U.S. and France. The flimsy plot is a series of encounters between the titular (heh heh) Candy, who is encouraged by her respected philosophy professor go out and “give her love” freely, and a collection of degenerate authority figures bent on exploiting her attempts to do just that, including (but not limited to) that same professor (of course), her own uncle (who happens to be her father’s identical twin for an extra layer of perversity), and several doctors and therapists, including masturbation proponent Dr. Krankeit (Hoffenberg’s contribution.) The self-contained hunchback story that started the whole thing is now Chapter 10, and it’s the stand-out sequence of a tiresomely repetitive series of seductions/rapes, in both the extremity of its twistedness, and in that the psychotic hunchback does not desire Candy physically (at first), but merely wants to rob her.

Candy was finally published legitimately in the U.S. under Southern’s and Hoffenberg’s real names by Putnam in 1964. Southern had long since moved on with his life and career by then, and by his own admission, Candy was a one-joke premise that went on too long. Having read the thing myself (it’s a $3.99 Kindle if you look for it under the Kenton name), I couldn’t agree more. Candy is an incredibly tedious read. (As for it being a send-up of Volatire’s Candide? Probably hogwash. It seems someone decided on that interpretation after the fact, and Southern and Hoffenberg simply went along with it to give their project a whiff of intellectualism. “Yes, of course, it’s a send-up of Candide.”)

Then someone decided to turn it into a movie.

Maverick United Artists director/producer Frank Perry (David and Lisa) thought the book’s notoriety and popularity (it somehow reached number one on the bestseller list in America without anyone admitting to having bought a copy) gave it great potential as a film, even as it was making its way through lawsuit hell over various copyright and intellectual property issues between the authors, Olympia, and Putnam. (You can read about all that legal stuff in excruciating detail in Nile Southern’s The Candy Men.) How would the blatantly pornographic novel be translated into something that was showable on a pre-ratings, mid-’60s cinema screen? Well, that was a problem for the screenwriter.

Perry thought the logical solution was to hire Terry Southern himself (by then hot off co-scripting Dr. Strangelove) to write the screenplay, and he got through three drafts fueled by scotch and amphetamines before the U.A. deal fell through. The copyright nightmare was unresolved, and Southern’s script was still far too outrageous.

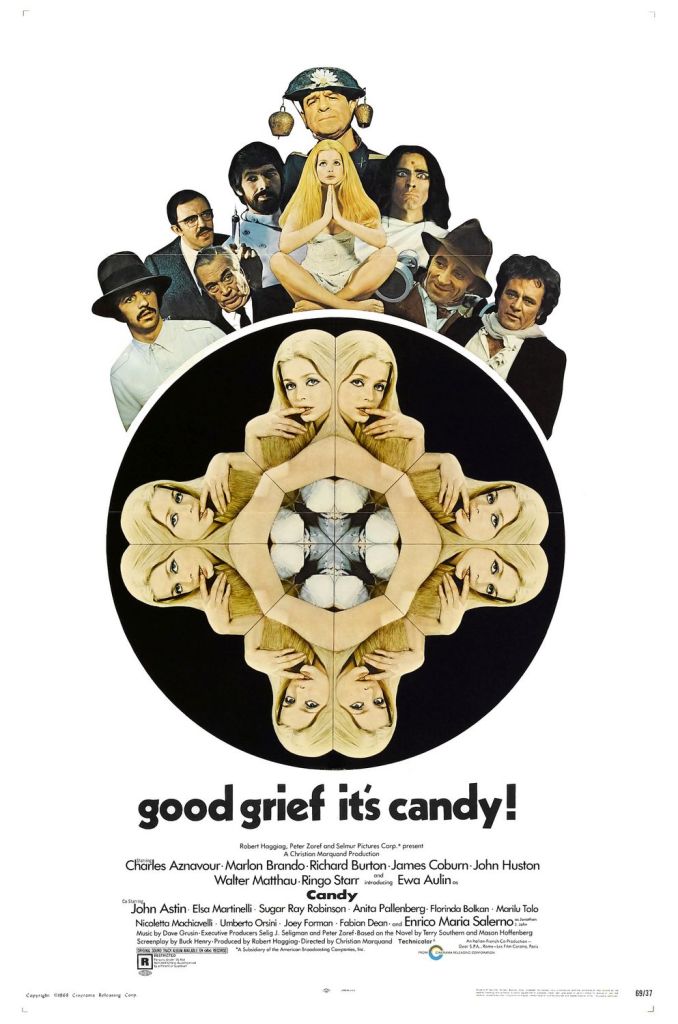

Enter Christian Marquand. A French actor (And God Created Woman, The Flight of the Phoenix) and close friend of Marlon Brando (Brando named his ill-fated son after him), Marquand came sniffing around the property as a vehicle for him to fulfill his directorial ambitions. As soon as the legal situation was resolved in early 1967, Marquand pounced. His celebrity contacts would attract the necessary financial backing. Brando would certainly be in it, and Marquand said he had both Richard Burton and Peter Sellers on board. On that basis, a Libyan-born financier and studio owner named Robert Haggiag agreed to produce.

The Candy movie got the green light. Southern’s too-explicit script was dumped in favor of a tamer version by Buck Henry. Henry, co-creator of TV’s spy spoof Get Smart, was, like Southern, on a pretty hot screenwriting streak, having just finished writing The Graduate. Henry used the basic premise of the book and some of the characters, then tossed the rest with Marquand’s blessing. “We’re going to throw the book away, and dig in,” said Marquand proudly, eager to put his own auteur stamp on the material.

While Candy was in pre-production, the Beatles released Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, which featured none other than Terry Southern among the crowd on its iconic cover.

Peter Sellers dropped out of the project in favor of an instantly-dated hippie flick, I Love You, Alice B. Toklas (if he had ever actually agreed to be in Candy to begin with), but Richard Burton dutifully made an appearance, and Brando’s presence was a given. A gaggle of other celebrities who thought it might be fun to goof around in an adaptation of one of the decade’s most notorious books eagerly signed on to play the story’s ensemble of grotesques. Everyone converged on the sound stages of Haggiag’s Dear Studios in Rome in December of 1967 for what was sure to be a wild time.

Joining them was Ringo Starr.

Ringo as Emmanuel

Ringo had fulfilled his Beatle duties for the year. Sgt. Pepper had been a triumph that summer. Their plotless, psychedelic 50-minute TV movie Magical Mystery Tour was in the can after a September/October shoot, ready for a poorly-received Boxing Day premiere. Their new single, “Hello Goodbye,” had been released on November 24 (it shot to #1 and stayed there for seven weeks), and the Magical Mystery Tour soundtrack would hit British shops on December 8. Ringo’s last official band work before jetting off to Rome was to shoot a promo film for “Hello Goodbye,” featuring the Beatles performing the song in their Sgt. Pepper uniforms, on November 10, and taping their annual Christmas message for their fan club on November 28.

CANDY

Released: December 17, 1968 (U.S.)

Director: Christian Marquand

Producer: Robert Haggiag

Screenwriter: Buck Henry, based on a novel by Terry Southern and Mason Hoffenberg

Studio: ABC Pictures, Corona Cinematografica, Dear Films, Selmur Productions, distributed by Cinerama Releasing Corp.

Cast: Ewa Aulin, John Astin, James Coburn, Marlon Brando, Richard Burton, Charles Aznavour, Elsa Martinelli, Walter Matthau, Ringo Starr, John Huston, Anita Pallenberg, Sugar Ray Robinson, Enrico Maria Salerno, Umberto Orsini, Joey Forman, Fabian Dean, Buck Henry

No one seems to remember how a role in Candy came to Ringo in the first place. It may have been through his friendship with Peter Sellers. Ringo recalled in an on-set interview that an unnamed “they” offered him the role of Emmanuel the gardener. “They didn’t offer me a choice [of parts]. They only asked me to play the lust-mad Mexican gardener.” Ringo seems to have taken the part to have a bit of a break from the Beatles (even with no touring, ‘67 was a busy year), it fit his schedule, and because someone simply asked him to be in it. Like almost everyone else on the planet, he had read the book. “I thought, ‘You’re joking. How can they make that into a film?’ ‘Randy’ isn’t the word for it. [Making the film] was the mind-blowing experience of my life. I was filming with Marlon Brando, Richard Burton…wow!” He then added he would really preferred to have played the hunchback.

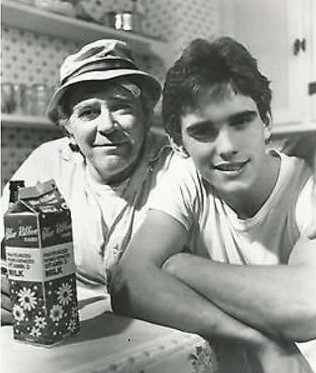

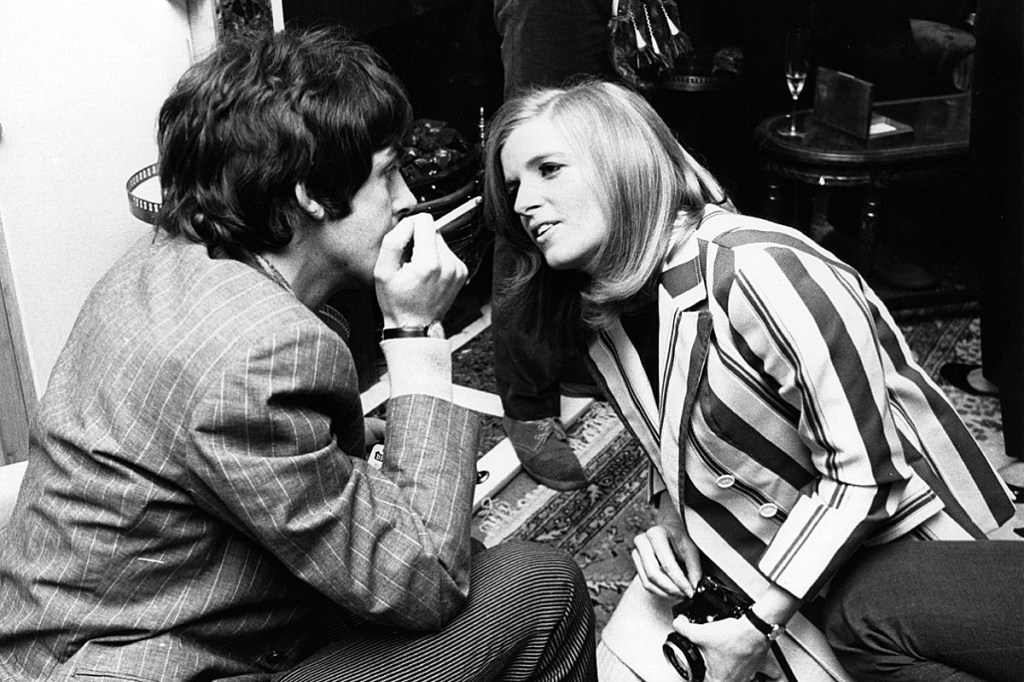

Ewa Aulin and Ringo in Rome, December 1967

Ringo arrived in Rome on December 3, 1967. His chestnut hair was given a hasty black dye job, and it was decided that the mustache and soul patch he had been sporting all year suited the character quite well. He was in front of the cameras beginning December 7. He filmed for just over a week, wrapping his part on the 16th, and returning to London on the 17th. Some of his co-stars, like James Coburn, remember the Candy shoot — nostalgically — as an undisciplined, freewheeling parade of bad behavior very suited to the era and the material. Although he already had a reputation as something of a party animal, no one recalls Ringo participating in the bacchanalia of sex and drugs that permeated the shoot. He spent most of his after-hours time hanging out with Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor on their yacht. Long after Ringo had finished his part, the production moved to New York and California for location shooting, and finally wrapped in April of 1968.

Amid all the celebrities on display, who would be the film’s anchor? Who would play Candy? Haggiag and Marquand chose Ewa Aulin of Sweden. A petite, wide-eyed, pouty-lipped blonde, Aulin certainly had the “sex kitten” look, but her grasp of English was tenuous at best. Southern was disappointed. He felt Candy should be an all-American apple pie Midwesterner. But he knew the film adaptation was beyond his control, and Marquand wanted Candy to have a more “universal” quality. Aulin was Miss Teen Sweden of 1965, and Miss Teen International of 1966. Naturally, she attracted the attention of a bevy of slightly shady European film producers, and had appeared in a couple of low-budget Italian films which put her on Haggiag’s radar.

According to some sources, Aulin had the same effect on her co-stars as Candy had on the characters they played. She was hit on constantly, and one actor’s groping “attention” — let’s just call him “Harlon Frando” — shocked even the other cast members, who were not exactly models of restraint. (Glad to report that Ringo by all accounts was a perfect gentleman, and Aulin later spoke of him fondly.)

The actors all seem as if they had just glanced at the script for the first time right before the cameras rolled (this may indeed have literally been the case in a few instances). Not that it was much of a script anyway. Buck Henry’s considerable gifts have deserted him here. (“I wish I had written a better script,” Henry frankly admits in one of his last interviews before his death in 2020.) The dialogue is clunky and not particularly funny. It is supposed to be a comedy, but it mistakes eccentricity for humor. Admittedly, the eccentricity can be fun to watch in a few sequences, but there’s no earthly reason for the official cut of Candy to run just over two hours.

Continue readingFiled under Film & TV

From the Archives, 2008 — The Holy Bee’s Top 5 Monster Movies

The Films of the Solo Beatles series will continue in March (hopefully). January turned out to be an unexpectedly busy month, so watching those films, taking notes, researching their production and other minutia, and then writing it all up in a breezy 5000+ words just wasn’t in the cards.

The following article originally appeared in the Idle Times zine, Issue #1 (Fall 2008). Please note that some strident opinions have softened or changed entirely over the last decade-and-a-half, and there are some turns of phrase I would not have chosen at a later point in my writing “career.”

“There were giants in the earth in those days, and also afterward…” — Genesis 6:4

“Everybody said there was no honed iron hard enough to pierce him through, no time-proofed blade that could cut his brutal blood-caked claw…” — Beowulf, l.983-89

Human beings are by nature vulnerable. We have no thick hide, no tusks (unfortunately — wouldn’t that be cool?), nor any natural camouflage. We’re just six-foot tubes of delicious pink meat. All we have to protect ourselves is our comparatively turbo-charged brains — which is a double-edged sword. We have the mental ability to dominate the natural world, but also the ability to scare ourselves by imagining the most unnatural horrors.

When primitive humans huddled around the fire, they told tales of what lurked beyond the sheltering ring of light. Shaggy or scaly things, with sharp claws and dripping fangs. Waiting for a dim-witted or simply unlucky Cro-Magnon to wander just far enough into the darkness…

The best monster movies tap into this primal fear that’s been hard-wired into our psyches. So, what truly defines a “monster movie”? First of all, it doesn’t necessarily have to be a “horror” movie (although it helps), it just needs to make us humans feel very, very defenseless. Monsters should be an external threat. None of this “the-worst-monster-is-inside-us” psychological bullshit. So Hannibal Lecter, Joan Crawford, and their ilk are out. (Sorry, Mommie Dearest fans.) Monsters are also a very corporeal threat. Scary as they can be, ghosts are not monsters. Not even if they can wreak havoc in the physical world. No poltergeists, demons that make you do unspeakable things with a crucifix, or Freddy Krugers. The jury’s still out on whatever the hell Jason Voorhees and Michael Myers are. They are certainly physical, but their inability to be permanently killed suggests ghosts or “undead” as opposed to human. But it’s a moot point because 1) their movies are really shitty (except for the first Halloween), and 2) I am officially declaring the “Unkillable Slasher” film to be its own separate genre, and you can read all about it in the Things That Suck ‘zine. But not here.

So to sum up, a monster should be able to eat you, stomp on you, or at the very least, carry you off…

#5 — The Undead

THE BRIDE OF FRANKENSTEIN (1935)*

The performance by Boris Karloff as Frankenstein’s Monster was a double triumph. It combined a simple sensitivity with the ever-present threat of hulking brutality. The make-up designed by Jack Pierce is positively iconic. No modern audience can think of the Monster without picturing the lank black hair over a squared-off skull, the green-tinted skin, the neck bolts — all from the imagination of Pierce. (Why green make-up? It photographed as the perfect shade of corpse-like gray on black-and-white film. Gray make-up would look too white. Some color stills were released to the press, and the Monster has been imagined as green ever since.)

Bride of Frankenstein ranks slightly above the 1931 original in most people’s opinion because it incorporates a lush score (like many early talkies, the original had no music), its eerily beautiful set design, and visionary director James Whale’s imagery and highly theatrical humor. For those of you who dig subtext, watch for all the religious themes and iconography, and the homosexual undercurrents. Ernest Thesiger as Dr. Pretorious might as well be credited as the first openly gay leading character in film history. (No, he doesn’t come right out and say it — this was 1935, after all. But some of his cleverly insinuating dialogue and the entire physicality of his performance left no one in any doubt, even in 1935.)

When it comes right down to it, as dated as they sometimes seem, all monster movies owe a tip of the hat to the classic Universal Studios monsters of the 1930s and ‘40s. Human-sized, awash in pathos, these creatures did not ask to be what they are — but if you cross them they will fuck you up.

#4 — The Hubris of Man

GODZILLA, KING OF THE MONSTERS (1956)

Saturday night/Sunday morning. 3 AM. Can’t sleep. Sandwiched between infomercials and increasingly desperate Girls Gone Wild ads, one can usually find an old monster movie. Count yourself lucky if it’s Godzilla, King of the Monsters. (Count yourself cursed if it’s the 1998 travesty of a remake.) GKOM is the U.S. version of the 1954 Japanese original Gojira, about nuclear fallout that brings to life an enormous mutant dinosaur. The film was Americanized by toning down the bitter recriminations over Hiroshima, and adding footage of Raymond Burr as an American reporter (“Steve Martin ”) in Japan. He interacts with the Japanese cast through the use of body doubles and clever editing, and the process is surprisingly well done.

Despite the editor’s scissors’ careful elimination of too many references to a certain country using a certain weapon on a certain other country, make no mistake, Godzilla is clearly an atomic-powered monster. And he’s not the friendly nuclear dino of later sequels, defending the Home Islands against other mutant threats. No, in ‘56 he’s pissed. He rages, stomps, sinks ships, and burns thousands of innocents to a crisp with his radioactive halitosis. The lesson here is that there are Some Things In Which Man Is Not Meant To Meddle, and splitting the atom may just be one of them. Godzilla’s first appearance is quite late into the film, setting a pattern that all good monster movies of the future follow. Show little glimpses, show some damage and casualties, build up the tension before the big reveal. There’s no way to avoid the fact that the “big reveal” here reveals a guy in a rather cheap-looking rubber lizard suit, but if your powers of disbelief-suspension are strong enough, you’ll go along with it.

Collector’s Note: After decades of unavailability, the 1954 original can finally be obtained as a bonus disc included with the 2006 GKOM DVD. At the risk of angering purisits, it’s no better than the U.S. re-cut. It’s about 15 minutes longer, and most of that is emotional discussions about atomic energy.

#3 — The Thing From “Out There”

ALIEN (1979)

“In space, no one can hear you scream,” ran one of the greatest taglines in cinema history. We’re talking primal fear, remember, and fear of the dark is one of our most basic. It’s why those cavemen huddled close to that fire. It’s why the majority of children sleep with the soft glow of a favorite cartoon character glimmering in a nearby outlet. It’s why me, a grown-ass man, will pop on my bedroom TV after a particularly vivid nightmare. Why do we fear the dark? BECAUSE WE CAN’T FUCKING SEE ANYTHING IN IT. It doesn’t get any more basic than that. Who knows what’s lurking where we can’t see. Escaped circus animals, psychotic dismemberment aficionados off their meds, and…monsters. There’s always that possibility. We know there’s “no such thing,” but that assuredness slips just a tad in the dark, doesn’t it? And what is outer space but airless, silent, eternal dark? Midnight that goes on to infinity. And our confident daytime knowledge that there’s no such thing as monsters isn’t worth a bronzed turd, because we don’t know what such things could be…out there.

Maybe aliens are gentle, elf-like beings with glowing fingertips and hearts, and big, expressive anime eyes. Or maybe aliens are slavering, nine-foot insectoid beasts with a double set of jaws and a taste for human flesh, not to mention the ability to move at blinding speeds and lay their eggs in live human hosts by ramming an ovipositor down their throats, which “hatch” several days later in Technicolor glory right as the human host is sitting down for a nice meal after recovering from the earlier (very traumatic) ovipositor incident.

Guess which one this movie’s about?

Continue readingFiled under Film & TV, Pop Culture

Act Naturally: The Films of the Solo Beatles (Part 1)

Prologue: A Hard Day’s Night, Help!, and Ringo the Actor

When I was a super young Beatles fan in the early ‘80s (age 7-10 or so), there wasn’t much beyond the music itself and a couple of books out there to feed my fandom. So when PBS decided to show the 1982 documentary The Compleat Beatles a few years after it came out, I made sure I was rolling VHS tape on it. In subsequent years, I literally wore out the tape watching and re-watching it. It ended with a brief summary on the activities of each individual Beatle after the break-up. Here’s Ringo’s:

That always puzzled me. “An acting career in Hollywood?” I went to the movies a lot as a kid, and I’d never seen any movie starring Ringo Starr. This statement was also echoed in the handful of Beatles books I had collected. Everyone agreed without contradiction that Ringo became an actor in the 1970s.

As it turns out, this is a bit of an overstatement. Ringo’s acting career never amounted to much, and the film work he did was pretty well removed from anything that can be described as “Hollywood.”

But thinking about all this recently did get me interested in exploring the work of the solo Beatles on film, one element of their careers that I never delved into all that much.

Collectively, the Beatles were movie stars by the middle of 1964.

There was once a time (the mid-20th century) when a popular singer could reach such a level of universal fame that they would be elevated past being a mere “singer,” to become an “entertainer.” They would be expected to not only sing and continue to sell records by the bushel, but also act in films, and appear on television (frequently poking good-natured fun at themselves in comedy sketches and the like). Bing Crosby, Frank Sinatra, Elvis Presley, and several others made the cross-over. It was all just homogenous “show business” at a certain point. By the early 1960s, even bands like the Beatles were expected — almost required — to follow the established path. Of course, it was bands like the Beatles and their contemporaries who put an end to this kind of thing by creating the world of modern rock and rebelling against old-school showbiz traditions. But in their early years, they really felt they had no choice but to play along. In October 1963 (when they had been famous in Britain for less than a year and hadn’t broken in the US at all), Beatles manager Brian Epstein signed them to a three-picture deal with United Artists.

It didn’t matter that none of the Beatles expressed an iota of interest in acting, because United Artists didn’t have an iota of interest in the Beatles as actors. They wanted the lucrative rights to the soundtrack album, which they hoped to cash in on before the Beatles fad died (as everyone was certain it would, any week now). Someone could have filmed the Beatles reading the phone book against a blank wall, and as long as some songs were interspersed in there, UA would be happy. Luckily, that’s not what happened.

What happened was they ended up making a really good movie.

While contract negotiations were underway, United Artists producer Walter Shenson had a lunch with Richard Lester, who had just directed the Mouse That Roared sequel (The Mouse on the Moon) for Shenson and UA. When Shenson mentioned he would likely be handling an upcoming Beatles film, Lester eagerly asked if he could direct it. Shenson thought it was a wonderful idea.

Lester — described by singer/writer/eccentric George Melly as “an amiable space creature, very thin, with a great domed bald head, tiny childlike features and large kind eyes” — was born in Philadelphia, but had been working in television in the UK since the early 1950s, and had a couple of feature films under his belt by late 1963. He was 31 years old when he took on the Beatles’ first film, very youthful by today’s standards, but in the world of early ‘60s pop music, where both artists and fans were in their teens or not much past, he was an “adult.” A sophisticated lover of classical music who was a decent hand on the piano, no less. But unlike a lot of other “adults,” he did not necessarily look down on pop music, and the Beatles were on his radar pretty early. And when the Beatles heard Lester had been tapped to direct their movie, they approved wholeheartedly. They knew Lester had directed The Running Jumping & Standing Still Film, a surreal short featuring their comedy idols, Goon Show stars Spike Milligan and Peter Sellers.

Lester brought in Liverpool playwright Alun Owen to craft a script. (As a writer, Owen was so closely associated with Liverpool that Epstein reached out to him about the possibility of writing a Beatles script even before the UA deal was conceived, and likely pointed Lester in his direction.) Owen traveled with the band during their two-day trip to Ireland (November 7-8, 1963), and was able to distill their personalities and transcribe some of their witty remarks into his Oscar-nominated screenplay, which was an exaggerated “day in the life of the Beatles.” Aware that the group had no experience as professional actors, Owen made sure that no Beatle had more than one line at a time. Lester had a tight schedule (six weeks in March and early April 1964) and a modest (but by no means tiny) budget, so he used the limitations to his advantage, presenting the band in a gritty, black-and-white, semi-documentary style.

When A Hard Day’s Night hit cinemas in the summer of ‘64, the established film critics found themselves astonished that they actually enjoyed a movie about a bunch of pop musicians. Their positive reviews carried almost a puzzled air. Could this be possible? Lester’s film was fast-paced, inventive, and a great example of deadpan British humor. All of the Beatles acquitted themselves quite well, but one member was always singled out by the critics for individual praise — Ringo Starr. Ringo had a lengthy solo sequence two-thirds of the way through the film. Feeling put-upon by his bandmates, he ditches rehearsals to go on a lonely ramble along the Thames. He projects an air of melancholy and vulnerability, and the viewers’ hearts go right out to him. (His secret to “acting” this scene? He had been partying all night the night before, never went to bed, and was sleepy and hungover as the cameras rolled early in the morning.)

Although all the Beatles were natural performers — they just exuded charisma — everyone decided that Ringo was the one who had the potential to be a true actor. So he became the central figure (not exactly “star”) of the Beatles’ next film, 1965’s Help! Lester was once again at the helm, and engineered a complete departure from the Hard Day’s Night style — this time he went with glorious Pop Art color, and a pretty silly “story” (originally concocted as a Peter Sellers vehicle) about a cursed ring on Ringo’s finger. It was essentially a live-action cartoon, and the critics weren’t quite as effusive as they were for A Hard Day’s Night. But the music was as good as ever, spoofing the globe-trotting James Bond series was fun, and once again Ringo was noted for the special quality he brought to the screen. The band even paid tribute to the budding Brando in their midst by recording a cover of Buck Owens’ “Act Naturally” with Ringo singing lead. They enjoyed a good working relationship with Lester, and considered him a friend.

There was one more film left on their United Artists contract, and if they followed the pattern of 1964 and 1965, then they would produce a film (and accompanying soundtrack album) for a summer 1966 release.

It did not come to pass.

A Talent For Loving and Up Against It

In the 1500s, an Aztec curse is placed on a Spanish conquistador…he and all of his descendants until the end of time will be consumed by insatiable lust from the moment of their first carnal encounter. Flash forward three centuries…Mexico, 1871. A prosperous ranch owner (and victim of the curse) is trying to marry off his virginal daughter before the curse “ruins” her. A series of competitions between two young ranch hands will determine which one has enough physical stamina to meet her needs and keep her honorably faithful in the bonds of matrimony…

This is the plot of A Talent For Loving or, The Great Cowboy Race, a 1961 novel by Richard Condon (famous at the time as the author of The Manchurian Candidate). It was an interesting attempt to combine a post-modern Western tale with an irreverent sex farce. In an odd move, Brian Epstein secured the film rights, envisioning this as a potential vehicle for the Beatles.

At what point “Beatles” and “Old West comedy about nymphomania” blended together in Brian Epstein’s mind is unclear (or maybe it was someone else’s suggestion), but it seems that the Beatles were big western fans, and evidently they had been bitten by the acting bug. They wanted to play actual characters instead of “the Beatles.” A screenplay written by Condon and his wife Evelyn was completed by March 1965 (literally while Help! was shooting), and it was hoped they could film in September. “No reason why Liverpool lads shouldn’t be out there [in the West],” said Condon confidently, “complete with accents, lariats, and six-shooters.” Walter Shenson was brought into the picture that summer, confirming this was to be the Beatles’ third UA release. But the film went into re-write hell — it seems it was more difficult than anticipated to incorporate four Liverpudlians into a western set in Mexico. The September shooting window came and went, because no one was happy with the script. By December, the project was dead. Times were changing fast, the Beatles were growing artistically by leaps and bounds, and they had soured on the idea of “playing cowboys” in a comedy. They also had genuine concerns about recording an appropriate soundtrack (19th-century Mexican balladry was not their forte). If they had to do another movie, they wanted something modern and cutting-edge. Epstein and Shenson went back to script hunting, still hoping to get a Beatles film into theaters sometime in 1966.

Any time the Beatles’ possible participation in a western comes up in discussion on a website, it is universally accompanied by one or more of these cowboy-themed images from a September 1964 photo shoot at the end of their summer tour of the US

[A Talent For Loving was eventually made in 1969, with Shenson still producing. It starred Richard Widmark (playing a middle-aged Civil War vet), Cesar Romero (playing the ranch owner), and Topol (playing a Mexican generalissimo with as much subtlety as the Frito Bandito). Obviously, none of these parts were suitable for the Beatles. I can only speculate that the two cowboys in competition for the rancher’s daughter would have become four cowboys, the four cowboys would also be British immigrants, and the parts would be much more fleshed out and important than the two hunky empty hats in the released version. Good ol’ Ringo probably would have been the victor.]

It soon became apparent that there would be no 1966 Beatles movie, but a contract was a contract, and there was always 1967. In late ‘66, Walter Shenson commissioned writer Owen Holder to craft a script that would meet the “modern, cutting-edge” requirement. Holder came up with Shades of a Personality, the story of a young man (Holder envisioned Lennon in the lead role) with three separate personalities, to be embodied by the other three Beatles. (Classic rock fans will recognize this as very similar to the Who’s 1973 concept album Quadrophenia.)

Holder’s script was met with little enthusiasm from the group. They really did not want to do another “Beatles” movie at this point. So desperate were they to not appear in front of the cameras that they tried to give United Artists an independently-produced animated film that had their likenesses (but not their actual voices) and a few new songs. Yellow Submarine was distributed by UA in 1968, but it did not fulfill their contract.

Hoping to entice them with edgiest of cutting-edge, Brian Epstein gave the Holder screenplay to Joe Orton for a re-write. Orton was the “bad boy” of British theater at that time. Plays like Loot and What the Butler Saw caused a sensation due to their explicitness and dark-humored nihilism. Orton began working on the Beatles project in January of 1967. He injected the material with a healthy dose of sadomasochism, polyamory, and gay subtext. He submitted the revised script — now called Up Against It — to the Beatles’ management. After several months with no word, the script was simply returned to him without comment. Free to entertain other options on the script, Orton was due to attend a meeting with producer Oscar Lowenstein and director Richard Lester on August 9, 1967. His body was discovered that day in his London flat, having been bluedgeoned to death by his boyfriend Kenneth Halliwell (whose body was nearby — he committed suicide by overdose). Eighteen days later, Brian Epstein died of an accidental overdose. (Paul McCartney admitted in 1997 that the Beatles had been frightened off the Orton project by the homosexual themes in the script.)

Less than two months after the death of their manager, the very first solo Beatle film would be released.

Here’s my format for discussing the films of the solo Beatles:

No TV movies, no concert films, no documentaries, no popping up as themselves in a cameo. These are narrative films released in cinemas in which they play a character. (I fudged it a little on Give My Regards to Broad Street in which Paul McCartney plays a “fictional” rock star that, based on all observable evidence, is pretty much “Paul McCartney.”) I will watch each film in its entirety at least once, most of them for the first time in many years, and a few of them for the first time ever. Release dates will generally be for the British release, unless otherwise noted.

Continue readingFiled under Film & TV

“A Christmas Story Christmas” Story

I’m always suspicious of people who claim to have no holiday traditions, although mine tend more towards “personal holiday observances, usually based around specific dates, that no one else really participates in.” I wrote about a bunch of them in some of my very first entries on this website, spreading them over three 2008 entries at a total length that would barely be half of a single 2020s-era entry. Obviously, much has changed since then. I’ve grown more long-winded in my website pieces, and more lax in observing many of my old traditions. However, the following five remain pretty iron-clad.

1. No Christmas music until after Thanksgiving. But as soon as the dishes are cleared away, I consider it open season for “Good King Wenceslas.” The Christmas Spotify playlist is usually on the car stereo driving home from Thanksgiving dinner.

2. Christmas lights on the house no later than the Sunday after Thanksgiving (weather permitting). This is often something I really have to force myself to do, tearing myself away from my fireside end of the sofa, my book, and the muted football game on TV to clamber around on a rickety ladder and almost plummet to a paralyzing injury at intervals that come closer together as the years roll on.

3. Christmas tree acquired and decorated on whatever weekend is closest to December 10. Any sooner and it dries up no matter how carefully I check the water level, any later and why bother?

4. Making a shepherd’s pie at some point in December (usually between the 20th and 23rd).

5. Having a bunch of Christmas-themed stuff on the TV. Cheesy variety specials, Christmas episodes of sitcoms, classic movies, you name it.

I say “having it on” instead of “watching,” because it’s usually just atmospheric background to my reading, computer gaming, or puttering around the house. I am a world-class putterer, and lately I’ve taken to doing it with my half-moon reading glasses perched on the end of my nose. Jesus, I’m old. Am I really the same person who used to go to Primus concerts with dyed blue-black hair (Manic Panic!) and army surplus pants tucked into shin-high black boots? I did scrupulously avoid the mosh pit, so I guess I was always kind of soft. But at least I was young and soft. (That didn’t sound quite right, but I’m leaving it in.)

One of the movies in the holiday rotation is A Christmas Story. Little regarded upon its initial theatrical release in November 1983, it has since become a holiday television staple in households across the country. So popular were its frequent airings on cable stations that Turner Broadcasting began showing it marathon-style — “24 Hours of A Christmas Story” — in 1997. For the last 25 years, starting at 8pm Christmas Eve and concluding at 8pm on Christmas Day, you could tune in and get your fill of Ralphie and his Red Ryder BB gun (with a compass in the stock and “this thing which tells time.”) You’d be joining roughly fifty million others.

Like Christmas music, the viewing of Christmas material on TV is strictly forbidden until after Thanksgiving. But this year, I violated tradition by watching A Christmas Story way outside of its normally-accepted viewing slot because I wanted to watch its brand-new sequel, A Christmas Story Christmas, the day it dropped on HBO Max. Watching a new sequel without a re-watch of the original is a violation of the Holy Bee Code.

As the consistently high annual ratings for the marathon have proven, the Christmas Story phenomenon is a powerful thing, and it’s woven firmly into the fabric of American culture. Even if you haven’t seen the film, it might feel like you have — it’s the story of nine-year-old Ralphie and his quest to get a BB gun for Christmas, while also dealing with his perpetually hassled mom and intimidating dad (only ever referred to as “the Old Man”), along with various other childhood dramas. You’ve probably heard about the notorious “fra-gee-lay” leg lamp, the tongue frozen to the flagpole, and the oft-repeated “you’ll shoot your eye out” catchphrase.

Full disclosure — I am not any kind of die-hard Christmas Story fanatic. It’s just tossed in with all the other holiday viewing for me. If it hasn’t been a part of a family tradition for years, this mild little period-piece comedy may actually be kind of a hard sell for new viewers who will undoubtedly wonder what all the fuss is about. But I did grow up with A Christmas Story, and I did get a warm tingle when I heard they were making a proper sequel. (And it just dawned on me that my Subscribe button is emblazoned with “I triple-dog dare you.” Maybe I am a die-hard fan.)

Wait, a “proper” sequel? Were there improper sequels? Yes, actually. Three of them, and they all failed for their own reasons, but mainly due to the issue that A Christmas Story Christmas intends to correct.

Never much liked the original poster, which failed to capture the true tone of the film — it made it look far too “wacky” and/or “zany,” the kind of movie where you’re just waiting for someone to get hit in the nuts and go cross-eyed.

The Christmas Story juggernaut started with Jean Shepherd (“Shep” to his legion of fans), a fixture of New York late-night talk radio from 1955 to 1977. Shep built a dedicated following by spinning lengthy first-person yarns about his alter ego, “Ralphie,” Ralphie’s family (“the Parkers”), and his experiences growing up in America’s heartland in a bygone era. You can get a taste of Shepherd’s engaging vocal style from his narration of A Christmas Story, portraying the unseen-but-constantly-heard adult Ralphie.

Although he insisted the tales were pure fiction and not autobiographical, elements of Shepherd’s real life always crept in. He really did have friends named Flick and Schwartz and a kid brother named Randy, he did go to Warren G. Harding Elementary School, and the name of his actual hometown — Hammond, Indiana (just across the state line from Chicago) — isn’t too far off from the fictional Midwestern town, “Hohman, Indiana,” that he created for his stories. He made the character of Ralphie a few years younger than himself to better align Ralphie’s childhood and adolescence with the Depression and the war years.

Jean Shepherd

What really blew people’s minds was that Shepherd told these stories off the top of the head. He prided himself on never relying on pre-written scripts, and could extemporize, ad-lib, spin off into side stories, and then tie it all up in a neat conclusion right as his closing music began to play. As his popularity grew, he began speaking tours of college campuses where audiences could verify this skill with their own eyes.

Someone finally asked Shep to put some of his favorites down in writing, and one of the first stories published was the one that provided the framework for A Christmas Story. “Duel in the Snow or, Red Ryder Nails the Cleveland Street Kid” appeared in Playboy magazine in 1964. (Playboy also sent him as a correspondent to tour with the Beatles for a few days later that year. A middle-aged jazz snob by then, Shep never warmed to their music, but admitted they were great fun to hang out with.)

Enough stories appeared in Playboy over the next two years to compile into a book. The result, In God We Trust, All Others Pay Cash, was published in 1966. Often described as a “story collection” or “anthology,” Shep always proudly referred to it as a novel. Despite this claim, it is pretty episodic, with the self-contained stories appearing as reminiscences between adult Ralphie and Flick during Ralphie’s return visit to his hometown. Only “Duel in the Snow” is Christmas-themed, and the other stories bounce around chronologically, with Ralphie depicted as anywhere from seven to fourteen, depending on the chapter.

Two sequels, Wanda Hickey’s Night of Golden Memories and Other Disasters (1971) and A Fistful of Fig Newtons (1981) continue the mixed bag of stories about (a mostly older) Ralphie.

Shepherd’s radio monologue about Flick getting his tongue frozen to a flagpole (a story that never made it into print) turned aspiring young filmmaker Bob Clark into a lifelong Shepherd fan. The eventual Christmas Story director contacted Shep as early as 1970-71 about making a film based on his stories, but it was a long road to production. They got as far as writing a screenplay, but no studio was interested.

The first attempt to tell a Ralphie Parker tale that made it to a screen was the TV movie The Phantom of the Open Hearth, which aired on December 23, 1976 as part of the PBS anthology series Visions. Shep wrote the script, and established a formula: a main throughline based on a key story from one of his books (in this case, the title story of Wanda Hickey), supplemented by secondary plot threads drawn from other stories (the leg lamp story from In God We Trust is first seen onscreen here) and from various unpublished monologues, all tied together by his voiceover narration.

The Phantom of the Open Hearth led to two (or three, kind of) more PBS adaptations, and they’re just this side of watchable if you can handle dingy, PBS-level production values, a much slower pace, and a few glaring differences from our beloved Christmas Story. The PBS Ralphie (re-cast each time) is depicted as an athletic, self-assured high school junior — a far cry from the awkward, needy, bespectacled little kid we’re used to. Flick comes off as a potentially dangerous criminal thug. Craggy character actor James Broderick (known for the ABC drama Family from the same era) is no Darren McGavin, but makes a pretty decent Old Man. (Just like no one is going to surpass Anthony Hopkins as Hannibal Lecter, you have to hand it to Brian Cox, who was the first actor to play the character — and did a good job — in the 1986 movie Manhunter.) Barbara Bolton as Mrs. Parker is the only lead actor to appear in all three, but she doesn’t exude a lot of personality, and only reminds the viewer of how much spark Melinda Dillon brought to the role. And, like most 1970s productions set in a previous era, no one would commit to period-accurate haircuts, so everyone kept their bushy ‘70s hair. (Another example: any given episode of M*A*S*H.) (The Phantom of the Open Hearth was re-cast and re-shot as a possible pilot for an ABC series in 1978, but it was never shown.)

Another PBS anthology series, American Playhouse, aired the second Shepherd adaptation. The Great American Fourth of July and Other Disasters hit TV screens on March 16, 1982, based around more In God We Trust stories. James Broderick returns as the Old Man (it was one of his final roles, he died later that year), and the characterization of Ralphie as “cool teen” reaches its zenith — he is played by none other than Matt Dillon. Like its predecessor, The Great American Fourth of July is acceptable, but nothing great. I was particularly disappointed that one of my favorite Shepherd stories, “The Endless Streetcar Ride Into the Night and the Tinfoil Noose” (about Ralphie on a blind date), was staged and shot in such a clunky and cumbersome way that it drained the story of its slow-building tension and brilliant comedic payoff.

The Star-Crossed Romance of Josephine Cosnowski was based mainly on Wanda Hickey material, and it aired on American Playhouse on February 11, 1985, after A Christmas Story had been ignored in theaters, but just before its big rediscovery as a TV treasure. Romance is a notch below the first two in terms of budget, humor, and performances. Despite the presence of a few vintage cars and kitchen appliances, all attempts to give it a period feel have been abandoned. The object of Ralphie’s affection looks more like Brenda Walsh from 90210 than anyone who would have breathed 1940s air. The usually reliable George Coe is a low-key, somewhat placid Old Man, with none of the bluster the part requires. (Coe is known to a later generation as the voice of Woodhouse on Archer.)

Bob Clark

Nobody ever went broke underestimating the taste of the American public, someone once said (it evidently wasn’t H.L. Mencken), and sure enough, Bob Clark’s Porky’s was a box office smash in 1982, giving Clark the clout to make whatever he wanted as his next project. He chose the Christmas-themed script he wrote with Shepherd many years earlier. Clark, who got his start in low-budget exploitation and slasher flicks, will likely never be in the Pantheon of Great Directors. He usually painted in the broadest strokes possible, and had a tendency to aim low in his comedy. But A Christmas Story has a subtlety that most of his other films lack. He was a potentially solid director (his pre-Porky’s Sherlock Holmes pastiche Murder By Decree was quite good) who had the misfortune to have directed mostly terrible films: The powerfully stupid Porky’s and its even worse sequel, feeble comedies like Rhinestone and Loose Cannons, whatever the hell Turk 182! was supposed to be, and the absolutely execrable Baby Geniuses, which played at the theater where I once worked and inspired more walk-outs than any other movie I can name. And those are just his movies people may have heard of. But not everyone can be Stanley Kubrick (luckily for Shelley Duvall), and Clark, by all accounts a genuinely nice man, had a personal warmth comes through in A Christmas Story’s informative commentary on the DVD. The kids in the cast loved him (unlike The Goonies’ cast, who were always a little afraid of grumpy old Richard Donner), and he clearly poured his heart into A Christmas Story. I was very sad to hear of his tragic death in a head-on collision on the Pacific Coast Highway back in 2007.

The film was shot from January to March of 1983, mostly in and around Toronto. The department store scenes were done at the actual Higbee’s in Cleveland. Another Cleveland location was the Parker house, located at 3159 West 11th Street. The interior scenes were shot on a Toronto soundstage, so the Cleveland location was for exterior shots only. It was purchased in 2004 by a California entrepreneur (who specialized in the production of replica leg lamps) and restored to resemble the house — inside and out — as it appeared in the film. Adjoining houses were converted into museum and gift shop space. (As of this writing, the whole complex is up for sale.)

A Christmas Story’s studio, MGM, did not seem to have much confidence in the final result. They put it into theaters in mid-November with little promotion, and it was mostly gone from screens by Christmas week itself. It wasn’t the box-office dud that legend later described it as, but its success was modest at best. It picked up a little traction when it showed on HBO and was released on VHS in 1985. Then came the turning point — a near-broke MGM sold most of its film library to Ted Turner in 1986, and A Christmas Story began its run on Turner-owned stations that holiday season. That’s when my family first watched it. It already felt like tradition by the following year. But don’t call it nostalgic. Both Clark and Shepherd insisted the film does not fit that description. “It’s not nostalgia. It’s an odd combination of reality and spoof and satire,” said Clark. Maybe that’s why newcomers to the movie are sometimes a little put off.

Continue readingFiled under Film & TV

Unboxing Revolver

“One thing I am always proud of is how the Beatles’ songs were so different from each other. Some other artists found a formula and repeated it. When asked what our formula was, John and I said that if we ever found one we would get rid of it immediately.”

— Paul McCartney, 2022

A quickie this month. I simply haven’t had time to put together another multi-part epic. But one is in the works, I promise. A two-parter, maybe three. Probably in early 2023. [2025 Ed. Note — It’s the Films of the Solo Beatles series, and it ended up as six parts.]

Yes, my day job has kept me very busy this autumn, but I have to face the fact that my off-hours have not exactly been dedicated to intellectual pursuits, such as researching and writing for this boondoggle of a website. (I have retired the term “blog” for myself because it smacks so much of a bygone early-2000s era, when a more innocent nation collectively fell in love with LiveJournal, Wonkette, and Juno.) When I get home from work and drop my bulk into my cat-scratched recliner, I am usually so mentally (and at my age, physically) wiped from the day’s work that I just want to stare blearily at something low-stakes until it’s time for roughly twenty minutes of Jeopardy! (skipping the commercials and the contestants’ awkward personal anecdotes). My wife and I compete over Jeopardy! in the most lax, informal manner possible. No one keeps track of points, and if our mouths are full of dinner when a response is required, we use the honor system. “I knew that. You know I knew that, right?”

And there is nothing that represents low-stakes viewing more than YouTube. There is a wide array of YouTube rabbit holes to trip up the shiftless and lazy. My twin go-tos lately have been: 1) Reaction videos. It’s peculiarly satisfying watching some innocent Gen Z’er come unhinged seeing The Exorcist for the first time, or a couple of fellow nerds nerding out (and even getting teary-eyed) over a Star Wars TV show trailer. 2) Relaxing footage of hobbyists painting miniature figurines for tabletop gaming. Mostly Warhammer 40K. The actual playing of Warhammer looks an order of magnitude less fun than painting the figures. (It seems you’re supposed to push them around on a placemat-sized cardboard grid.) If the painter/narrator has a soothing British accent, so much the better.

Which brings me to the most low-stakes YouTube genre of all, if such a thing is possible.

Unboxing videos.

People taking newly-purchased things out of their packaging, and describing the process. That’s it, and that’s all.

I’ve watched dozens.

Opening something new — especially something you’ve been anticipating getting for a long time — is an experience that can only happen once. Lots of folks out there share my opinion that half the fun is the aesthetically-pleasing packaging your new treasure arrives in. It was with great dismay that I finally forced myself to toss nine years’ worth of perfect little Pixel phone boxes. I ordered a cheap, off-brand external BluRay drive for my laptop the other day that came packaged like a tiara from Tiffany’s. (The BluRay drive itself turned out to be a piece of shit, but I wanted to put the box on my shelf.)

Don’t get me started on the sleek, gorgeous, modern-art masterpiece version of a covenant ark that a new laptop arrives in.

Despite my enthusiasm for splitting that shrink wrap with a well-practiced thumbnail and delving into the goods, I don’t think I’d ever bother to do an unboxing video myself, mostly because even that minimal effort seems like a waste of energy, and I doubt I’d come off well on video. My spindly paws are far from manicure-fresh, and like anyone with a soul, I cringe at the sound of my own recorded voice.

So I thought I’d do the next best thing and fill this space with some “unboxing” in pictures and text.

The August 1966 album that was the Beatles’ true masterpiece. For a long time, the following year’s Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band was hailed the pinnacle of the Beatles’ output (and as such, pretty much the pinnacle of popular music), but its baroque psychedelic fripperies have become a tad dated and indelibly associated with a specific, love bead-centric era. (Don’t get me wrong, it’s still the Beatles, and therefore essential, but you can almost smell the patchouli seeping out of it.) The more straightforward Revolver, on the other hand, is timeless, and a younger generation of Beatles fans have leap-frogged it ahead of Pepper, judging its merits more objectively without having been around for Pepper’s impact as a cultural phenomenon.

Here’s what I wrote about Revolver in the Idle Time collective’s 2009 book Decades: A Tribute to Our Top 400 Albums of All Time (where it easily sailed, by near unanimous acclamation, to the #1 spot).

“Assured and almost aggressively self-confident, the Beatles took their undisputed mastery of pure songcraft (melody, rhythm, lyricism, etc.) into the studio during their first long break from touring, and delved into a bag of production tricks and techniques that are still being emulated to this day. Varispeed, tape loops, flanging, phasing — all of which can be done in the modern era with the click of a mouse, but in 1966 required a pioneering spirit and a willingness to push the limits of recording at all times. It required thinking way, way outside the box, and altering (sometimes even damaging) microphones, instruments, amps, and four-track tape machines. (Yes, it was all done on four-track!)

Revolver is like a prism — a seamless crystalline whole, but depending on which angle you approach it from, will provide a brilliant, colorful flash of each band member’s personality. John Lennon’s lazy, swirling material (“I’m Only Sleeping,” “She Said, She Said”) reflects his own feelings of being adrift and confused early in the post-Beatlemania phase of his life, and his dabbling with the still-legal hallucinogen LSD. The album’s cacaphonous closer “Tomorrow Never Knows” is an attempt to convey the sensation of of an acid trip through pure sound…when he wasn’t tuning in and turning on, Lennon amused himself with satirical character sketches (“Doctor Robert”) that foreshadowed later figures like Mr. Kite and Polythene Pam. Paul McCartney’s songs showcase the skills of a master pop craftsman. “Here, There, and Everywhere” and “For No One” relate the beginning and end of a love affair in heartbreaking detail. The bouncy rhythms and positive vibes of “Good Day Sunshine” and “Got To Get You Into My Life” are the blueprints for Wings and the best of McCartney’s solo career. (Macca Bonus: His fluid, melodic bass-playing anchors the whole album perfectly.) George Harrison’s wry cynicism is our first taste of Revolver, as his stinging “Taxman” kicks off side one with its overdriven guitars and bitter lyrics telling the true-life, nouveau riche tale of losing 90% of your income to Britain’s harsh tax laws. No one wants to hold anyone’s hand here. His “Love You To” kicks off the ‘60s obsession with all things Eastern. The rest of the band sits this one out in favor of an all-Indian instrumental backing, with George singing earnestly of Hindu enlightenment in a thick Liverpudlian accent. And Ringo drums his heart out and sings “Yellow Submarine.” What more could you ask?

What the Beatles finally emerged from the studio with in the summer of ‘66 was the platonic ideal of a Great Album — sublimely-crafted songs that incorporated envelope-pushing experimentalism and stylistic shifts from track to track, and leaving the listener feeling like they’ve had an experience.“

Yes, the prism simile needs work, the band was more active on “Love You To” than I had assumed, and I somehow failed to mention “Eleanor Rigby,” but I still think that’s a pretty decent chunk of musicological expounding by a younger version of the Holy Bee. (Sorry, folks, but the book’s first and only limited print run sold out years ago. It was self-financed by our music collective, and it’s a good thing we didn’t have to pay by the adjective.)

A big trend in classic rock re-issues in the last few years has been “Super Deluxe Editions” — lavish box sets with several CDs and/or vinyl LPs crammed with fully re-mastered mixes, demos, and outtakes, usually accompanied by other collectible material. Late-period Beatles releases (1967’s Pepper through 1970’s Let It Be) have all received the Super Deluxe treatment under the supervision of Giles Martin (son of original Beatles producer George Martin), but no one was sure if such extensive re-mastering would work for the pre-Pepper stuff due to more primitive recording techniques prior to 1967. Luckily, recent technological breakthoughs have allowed Martin to apply his sonic magic to Revolver. (Click here for the audio-geek details.) It remains to be seen if earlier Beatles albums are suitable for Super Deluxe consideration, but I hope at least Rubber Soul gets the works.

Naturally, I clicked the button for the Super Deluxe Revolver as soon as it became available for pre-order. Here’s what arrived the other day:

Continue readingFiled under Music -- 1960s

Apple Scraps: The Odds & Ends of “Get Back”

Will I ever write a one-part Holy Bee entry again? This one was intended to be a one-shot. A throwaway, even. Just some random observations and lots of images. But my usual over-writing and lack of editing discipline caused it to bloat up, as if it had eaten fistfuls of instant mashed potato flakes right out of the box (don’t do that). To quote Abraham Lincoln, “As the preacher said, ‘I could write shorter sermons, but once I get started I get too lazy to stop.’”

I toyed with idea of dividing it into two entries.

But no! It’s staying a one-parter because it’s a stupidly indulgent entry, and just not worth spreading over two monthly installments. Word count-wise, I managed to keep it on par with a typical entry here, but all these pictures…your scrolling wheel may wear out before you get to the end. Read with caution.

Anyway, on with it…

Get Back, Peter Jackson’s landmark three-part series on the filming & recording sessions that ultimately produced the Beatles’ Let It Be album and documentary, has been out for almost a year now. It has inspired websites and podcasts to do recaps, reviews, and “deep dive” analyses of the development of the songs, and especially the interpersonal relationships and late-period band dynamics that give this project such dramatic heft. And everything from George Harrison’s color-coordinated outfits to the copious amounts of toast the band consumed (the toast rack seemed to be an essential piece of studio equipment) has been remarked upon many times.

I will try to avoid the most talked-about and analyzed stuff because I’m almost a year too late to that party. Mostly, I want to look at the little things that I noticed, or wondered about.

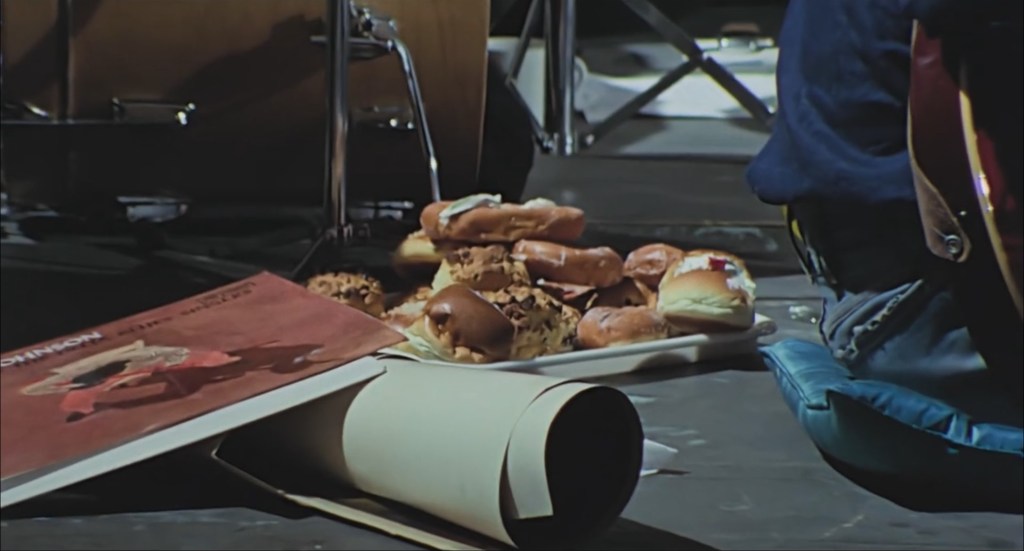

I mean, really inconsequential things. This is going to get ridiculous.

It’s all about clutter in the background or quick cutaways, and little bits of dialogue that didn’t get heavily mentioned, or mentioned at all, in the hundreds of other reviews and recaps. My observations are really lopsided towards Part 1, just because there was so much being introduced. Part 3 is almost non-existent here because there wasn’t much new to notice, a big part of it was taken up with the rooftop concert to which I have little to add, and frankly, I was getting a bit burned out by my “micro-watching” of this whole thing.

I will assume the reader is familiar with the overall story of the “Get Back” sessions, or has watched the documentary already, so let’s jump right in.

Part 1 – 12:42 — Does the Hare Krishna (identified as Shyamasunder Das) randomly hanging out on the Twickenham set really keep his few worldly possessions in a tartan handbag from Freddy, a high-end Paris gift shop?

Also, why exactly is he there? Clearly it’s at George’s invitation. After an initial meeting the previous month, George, whose interest in Eastern religion and philosophy was passionate, agreed to help the small religious group set up a London temple. Upon Paul’s arrival for the session, he and John dismissively refer to Shyamasunder with a few lines of dialogue from A Hard Day’s Night (“Who’s that little old man?”). Although a tacit supporter of the Krishnas (he let several stay on his property later that year), John finally makes the offhand remark, “It’s a bit daft him being up there, isn’t it?” Daft or not, a couple of Hare Krishnas come and go through the first few days of the Twickenham sessions.

1 – 13:12 — Sticker Time! (1): The Bassman sticker makes its first appearance. The sticker was originally included with the Fender Bassman amplifier that was part of a sweet deal made with Fender the previous summer. The company would send along instruments and amps they thought the Beatles would like, and also fulfill their requests — all for free, in the hopes of getting some promotion or endorsements, or even just having the Beatles be seen using the equipment. At some point Paul peeled off the sticker and applied it to his Hofner “violin” bass, where it stayed through the rooftop concert.

1 – 14:15 — Sticker Time! (2): Both Ringo’s rack tom-tom and his floor tom-tom sport a “Drum City” sticker. Drum City was located at 114 Shaftesbury Avenue in London, and naturally enough, it’s where Ringo got all of his drums starting in 1963. At that time, he acquired his signature Ludwig set with the black oyster pearl finish. Drum City owner Ivor Arbiter designed the world-famous “Beatles” logo to go on the bass drum head for an additional £5 “artwork fee.” Ringo’s most recent Ludwig kit from Drum City was acquired in September of 1968, and for the first time broke away from the black oyster pearl, going with a natural maple finish.