“The King’s great matter” it was called back in the late 1520s, a time when the Catholic Church was still the only church in England (although the Protestant movement was already well underway on the Continent)...

Even people who aren’t history nerds know about King Henry VIII and his multiple (i.e., six) wives. He burned through his last five wives in the final fifteen years of his life, but his first marriage lasted almost 24 years. Henry VIII of England and Catherine of Aragon had a complicated relationship to say the least.

To begin with, she was Henry’s brother’s wife first. Old Henry VII had arranged a marriage between his eldest son Arthur, the heir apparent, to the Spanish princess for her 200,000-ducat dowry. The pair were married when both were 15 years old, then Arthur fell ill and croaked eight months later. Catherine of Aragon was a widow at 16, and reported to everyone within earshot that the marriage had never been consummated. (Consummation of a royal marriage was considered a matter of state and certainly open for discussion by just about anyone.) And Henry VII definitely did not want to send back that 200,000 ducats. So he kept Catherine as his “guest” for several years until his second son, young Henry, was old enough to marry — even though it was expressly forbidden by religious law for a man to marry his brother’s wife. Still, 200,000 ducats was 200,000 ducats. A special dispensation had to be finagled out of the Pope based on the non-consummation of Arthur and Catherine’s marriage, and wedding plans went ahead.

On June 11, 1509, Catherine of Aragon, 23, married Henry, not quite 18. There was an empty chair at the ceremony as King Henry VII had died two months before. Catherine was marrying the new King of England, and the whole nation was waiting with bated breath for them to hurry the hell up and procreate already…

For the next decade or so, poor Queen Catherine produced a string of infants who were either stillborn or lived a few days or weeks at most. The lone exception was the future Queen Mary I…most decidedly not a male heir, which was what Henry believed he needed to secure the still-new Tudor dynasty’s future.

By 1525, Catherine was nearing 40 years old, and while it was still theoretically possible she could give birth to a healthy child, the reality was her track record of problematic births combined with her age meant that she was pretty much done with the whole reproduction thing. And her younger husband was clearly and publicly infatuated with one of her ladies-in-waiting, Anne Boleyn. Henry had already scored with her sister Mary, but Anne was proving a much tougher nut to crack (so to speak), refusing to pay a visit to the royal bedchamber without being properly married.

Thus began the “King’s great matter.”

Henry set about securing an annulment of his marriage to Catherine. He either believed, or told everyone he believed, that his marriage to her was cursed (and invalid in the eyes of God) because it violated the rule from the Book of Leviticus about marrying your brother’s wife. The special dispensation that allowed the marriage in the first place was now allegedly based on a mistruth — Henry avowed that Arthur and Catherine, being typical horny teenagers, did in fact consummate the marriage, and Catherine was a lying liar.

It was His Royal Majesty’s word against Catherine’s (who swore for the rest of her life she had never bedded down with Arthur). But even being a sovereign monarch, it would be difficult if not impossible to secure an annulment from the current Pope, Clement VII. At that time, the Pope was being held prisoner by Catherine’s nephew, Charles, who was doing double duty as King of Spain and as Holy Roman Emperor (and coping with the various infirmities and deformities caused by generations of enthusiastic in-breeding within the Habsburg dynasty). The Pope did not want to wreck his chances of release by booting his captor’s aunt out of her royal marriage, so the pleas from Henry’s messengers and letters fell on deaf ears. (If Charles had a verbal response, it likely would be incomprehensible and accompanied by a spray of saliva due to his enormous deformed lower jaw, referred to euphemistically as the “Habsburg lip.”)

The highest-ranking church official in England was (and remains) the Archbishop of Canterbury, who at the time was Thomas Cranmer, a Boleyn family friend and very recently an employee of the royal government, as England’s ambassador to none other than the aforementioned Charles. (One hopes he carried a good supply of handkerchiefs with him.) Henry pivoted to the Archbishop instead of the Pope to settle his great matter, and Cranmer took about ten seconds to review the case and said “Yup, your current marriage is invalid.” That was enough for Henry to marry Anne Boleyn in a secret ceremony in 1532. Catherine was stripped of her title of queen, and “banished” to a country life in retirement as “princess dowager” (based on her marriage to Arthur) with an ample allowance and a small army of servants, still loudly insisting she was Henry’s lawfully wedded wife. A more comfortable “banishment” cannot be fathomed, but I see her point. From this point on, when he mentioned her at all, Henry referred to Catherine as his beloved older “sister.” Anne Boleyn gave birth to the future Queen Elizabeth I in 1533, but no son.

Seeing that he had defied the Pope and not been struck down by a bolt of lightning, Henry spent the next year pushing a series of acts through Parliament that cut ties with the Catholic Church in Rome and established the independent “Church of England,” or Anglican Church.

Theologically, this was part of the Protestant Reformation that swept through Europe in the 1500s, setting up a variety of non-Catholic Christian churches, but the Anglican Church in Henry’s time still bore a striking resemblance to the Catholic Church. The only substantial difference was the king was in charge instead of the Pope. An entirely “new” religion was created pretty much out of pure spite, which may not be the stupidest reason to create a religion (it may not even be in the top five — see Scientology and its space aliens).

We won’t go into the fate of Anne Boleyn and the subsequent four wives here. All we need to know for our purposes is that the third wife, Jane Seymour, succeeded in producing a male heir. Edward VI became king when his father died in 1547, grossly overweight and riddled with ulcerated sores. The sickly Edward ruled only for six years, from age 9 to 15, before his own death, but during his reign his royal advisors worked hard to bring the Anglican Church more in line with other Protestant churches, who believed that all of the elaborate pomp and ceremony of the Catholic Church was inherently corrupt and blocked a worshiper’s direct connection to God. All the ornate vestments, gilded accessories, burning incense, red velvet, jabbering in Latin, and so on was considered entirely unnecessary and probably even sinful according to the Protestants.

Anglican church walls were whitewashed and stained glass was removed throughout the country in order to exude a more humble appearance. Liturgies in Latin were replaced by the Book of Common Prayer (written in English by Thomas Cranmer). Belief in transubstantiation, purgatory, praying to saints, rosary beads, and mandatory confession were all dumped. They kept the leadership structure of archbishops, bishops, and priests (referred to more as “vicars” as time went on) and a few other traditions.

Some bumps in the road aside (Queen Mary reversed England into Catholicism again in 1553, and her half-sister Queen Elizabeth switched it back to Anglicism in 1558, giving the whole country a case of ecclesiastical whiplash), the Church of England had firmly established itself as the 1500s ended.

But for some — your typical “small but vocal” minority — the Church of England’s practices were still too closely aligned with the Catholic Church, and not following the spirit of true Protestant reform as embodied by the ideas of Martin Luther and particularly John Calvin. The only way for the Church of England to provide a true path to salvation was to purge all similarities to the Catholics. To “purify” itself, as it were.

They were referred to as Puritans.

They practiced a form of “Reformed Christianity” called Congregationalism. They were technically still holding on to an Anglican identity by half a fingernail, but the reality was that the version of Christianity they established for themselves was very different from anything identifiable as Anglican. (More on Congregationalism when we get to the Salem Witch Trials. Stay tuned.)

For a still smaller minority of Congregationalists, this was not enough. To them, there was no hope to purify the Church of England. They wanted to separate from it entirely. Even the Puritans considered these guys to be overly-hardcore and unreasonable, and that’s saying something.

They were referred to as Separatists.

The Puritans and Separatists were isolated from mainstream English society, partly by choice and partly because they were just difficult to co-exist with. And if they got too outspoken with their criticism of the Church of England in a public forum (and many of them did), they could be fined or imprisoned.

The first to leave England to seek “religious freedom” were the Separatists, who began a slow trickle over to the Netherlands just before 1600. A specific group of about 300 of them, from the wonderfully-named village of “Scrooby” in Nottinghamshire, settled in Leiden in 1608. After resisting any attempt to assimilate, and terrified of their children turning away from their Separatist indoctrination and learning a more tolerant and open-minded worldview from the free-thinking Dutch (the whole reason the Separatists were welcome there in the first place), a portion of the Leiden Separatist community decided they would rather risk everyone’s lives and take a very dangerous chance on England’s brand new colonial territory in the North American wilderness.

This group of fanatical religious extremists are nowadays known affectionately as the “Pilgrims,” and still idealized in kindergartens across the country each November. They arrived after a tumultuous autumn crossing on the Mayflower near what was already known as Cape Cod in what would soon be known as Massachusetts in 1620. They established the Plymouth colony there.

To no one’s surprise but their own, most of the “Pilgrims” died in the first year.

(SIDE NOTE: The handful of survivors did in fact hold a “thanksgiving feast” the following autumn with some Native Americans attending, but — guest list aside — this was not out of the ordinary. Puritans and Separatists would have a thanksgiving feast at the drop of one of their buckled hats. Someone caught an extra fish? Let’s have a thanksgiving. Someone returned from market without getting mud on their breeches? Thanksgiving! It seemed to be their only form of release. The national holiday as we know it was not established until Abraham Lincoln did so in 1863 in gratitude for recent Union victories in the Civil War. Also, there was no turkey at the original 1621 dinner. Turkey were indeed abundant in New England, but they were wily and elusive, and no one could shoot well enough to bag one. All existing sources state that venison and seafood were the main courses. Sign me up, as that sounds much better than bland, boring turkey.)

Not long after the establishment of the Plymouth colony, things got really rough for the Puritans back in England, triggering a massive wave of immigration to Congregationalist-friendly New England. The Puritans’ much bigger Massachusetts Bay Colony absorbed the Separatists’ little Plymouth. Boston was established in 1630, named after a mid-sized town on England’s eastern coast that was considered the spiritual home of the Puritan movement. John Winthrop referred to it in a speech that year “the city upon a hill” — a model city that would have the world’s eyes upon it as a shining beacon of Christian virtue.

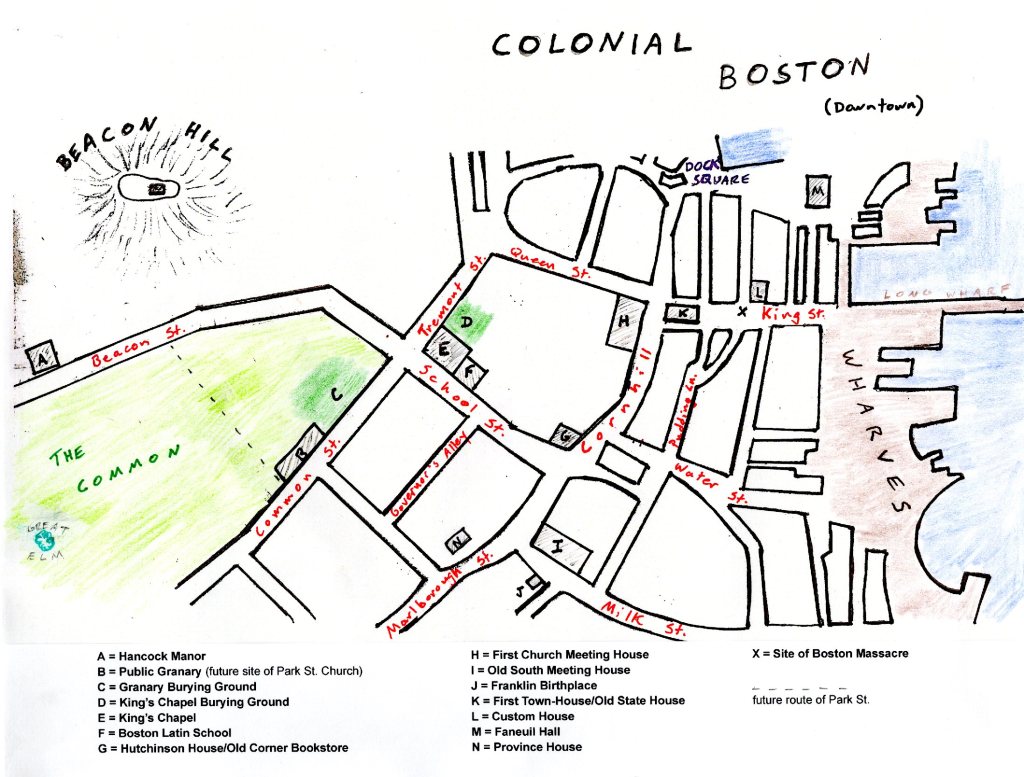

Just a few yards up Tremont Street from the Granary Burying Ground was #5, King’s Chapel & Burying Ground. The King’s Chapel Burying Ground is the oldest graveyard in Boston, established the same year as the city itself, 1630. Despite its name, it has no affiliation with the church it is adjacent to, and in fact predates the chapel by several decades. It was at first just called the “Burying Ground,” and as soon as a second graveyard was established, the “Old Burying Ground.”

The graveyard remained an active burial site until the 1800s, and as was the norm, the bodies were really jammed in there. The less than half-acre site contains more than 1,000 former people. About 600 tombstones remain visible, but like the Granary Burying Ground, do not necessarily correspond with the location of the person named on it. The most notable burial here is probably John Winthrop, often referred to as the Massachusetts Bay Colony’s first governor. That distinction actually belongs to John Endecott, who for many years was thought to be buried here as well, but analysis of local records uncovered that he is actually entombed in the Granary Burying Grounds (lord knows exactly where). Endecott’s name has been noticeably removed from the plaque on the entrance gate. (The quibble over who was the first colonial governor comes down to being appointed by the company that founded the colony — as Endecott was in 1629 — or elected by the residents of the colony — as Winthrop was in 1630.)

Also buried here is Mary Chilton Winslow, wife of merchant and ship-owner John Winslow, and mother of ten. Mrs. Winslow died and was put in her final resting place here in 1679. When she was a thirteen-year-old girl, Mary Chilton was purported to be the first person to set foot on land (the mythical “Plymouth Rock”) after the voyage of the Mayflower in 1620. This story is based on vague “Chilton family tradition” and was not put in print until 1744, so there’s obviously no way to authenticate it. However, it’s been pointed out that there has never been any rival claim to the honor in over 400 years, so why not? Let’s give it to Mary Chilton.

The Puritans dominated the city of Boston for decades, and even had a brief political reversal of fortune back in England in the 1650s, when Oliver Cromwell ran the whole country as “Lord Protector” (essentially a military dictator in the aftermath of the English Civil War) in keeping with his own religious beliefs until the old monarchy was restored after 11 years of Puritan rule.

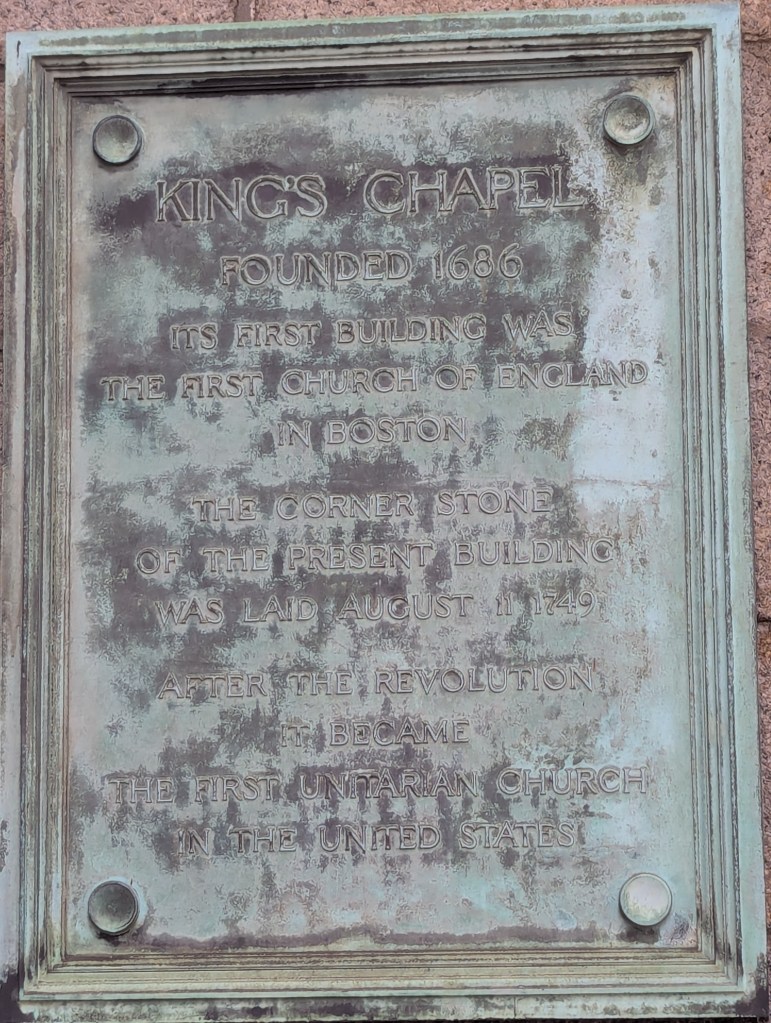

But try as they might, the Puritans could not keep non-Puritans from settling in the rapidly-growing city of Boston. By the 1680s, traditional Anglicans were numerous enough in the city to compel King James II to order the establishment of the first Anglican church in Boston. The Puritans dug in their heels, refusing to sell any land to the Anglicans for building their church. So the colonial governor, Sir Edmund Andros, seized some public land through the policy of “eminent domain.”

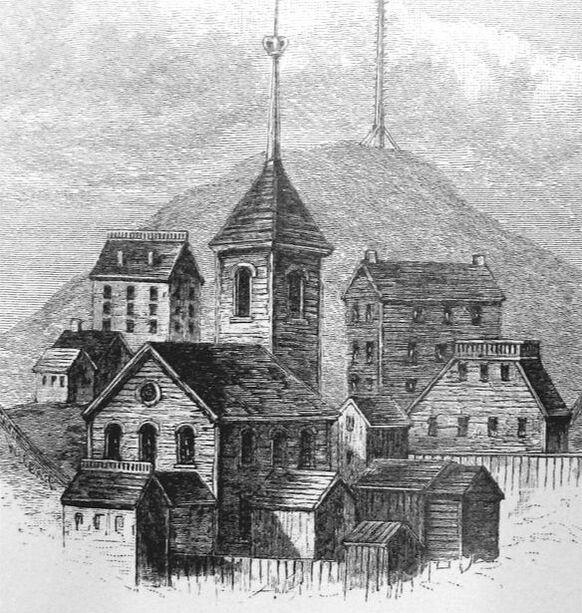

The parcel of land he took? A portion of the Old Burying Ground. The human remains were (hopefully) cleared from the space, construction began, and the first “King’s Chapel” was ready for Anglican services by 1689.

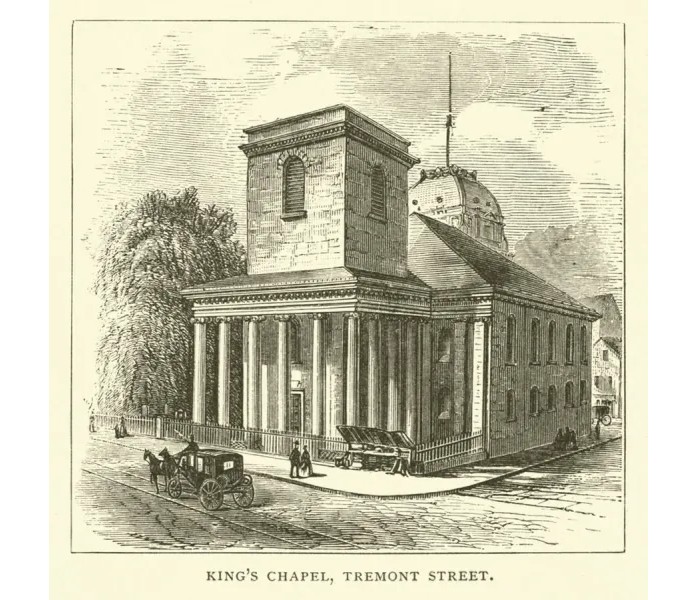

About sixty years later, the original wooden chapel was overcrowded and in a state of disrepair. A new granite King’s Chapel was built around the original structure while services continued uninterrupted, to ensure the land did not revert to the Puritans if the original structure was demolished. Only when the new chapel was completed in 1754 was the old one dismantled, and carried out in tiny bits through the windows of the new structure. The original box pews, communion table, Corinthian columns, and pulpit were kept. The pulpit, dating from 1717, is America’s oldest pulpit in continuous use in the same location.

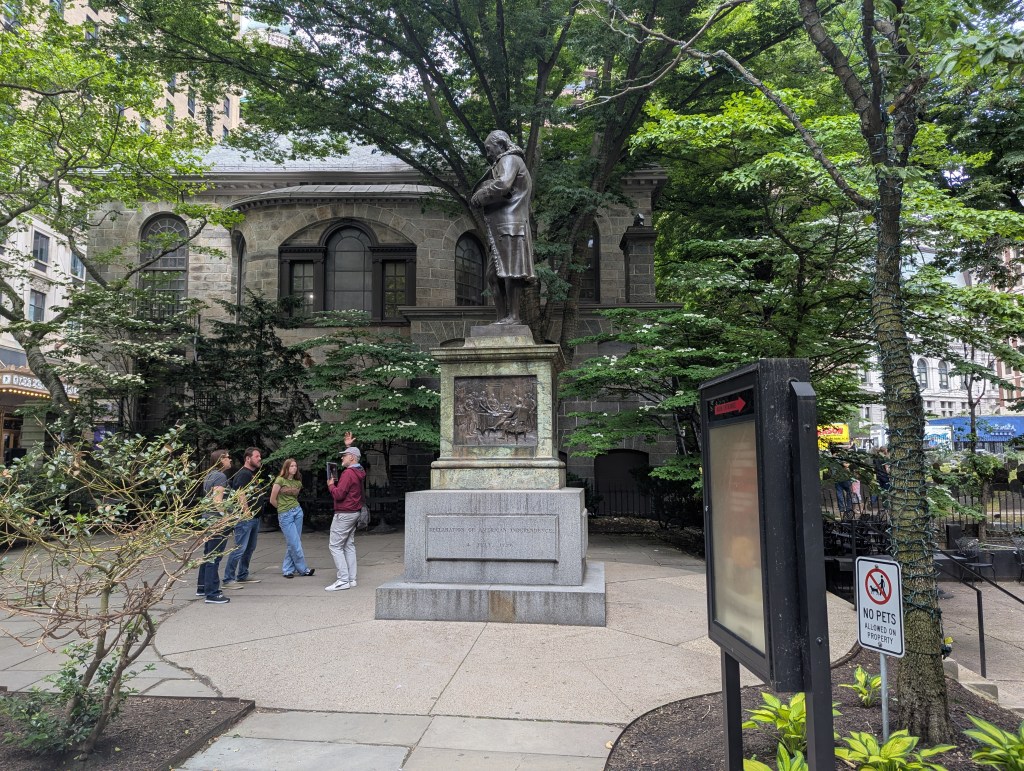

King’s Chapel’s clergy and most of its parishioners were Loyalists, so when the American Revolution broke out, many of them moved out of the area, and attendance dropped. In 1785, King’s Chapel became the first Unitarian church in the United States, four decades before the Unitarians had a formal organization. The bell in the tower was crafted by Paul Revere in 1816, and was his last major project.

Turning off Tremont Street and heading up School Street, we soon came upon the source of the street’s name. #6, Boston Latin School. Boston, as we’ve seen, is a city of “firsts.” Here we have the first public school in the United States, dating from before there even was a “United States.” It was public in the sense that it was free for students, funded by community donations and land rentals rather than traditional taxes. Rich or poor could attend, as long as they were a) male, and b) white. (The school graduated its first Black student in 1862, and only accepted girls beginning in 1972.)

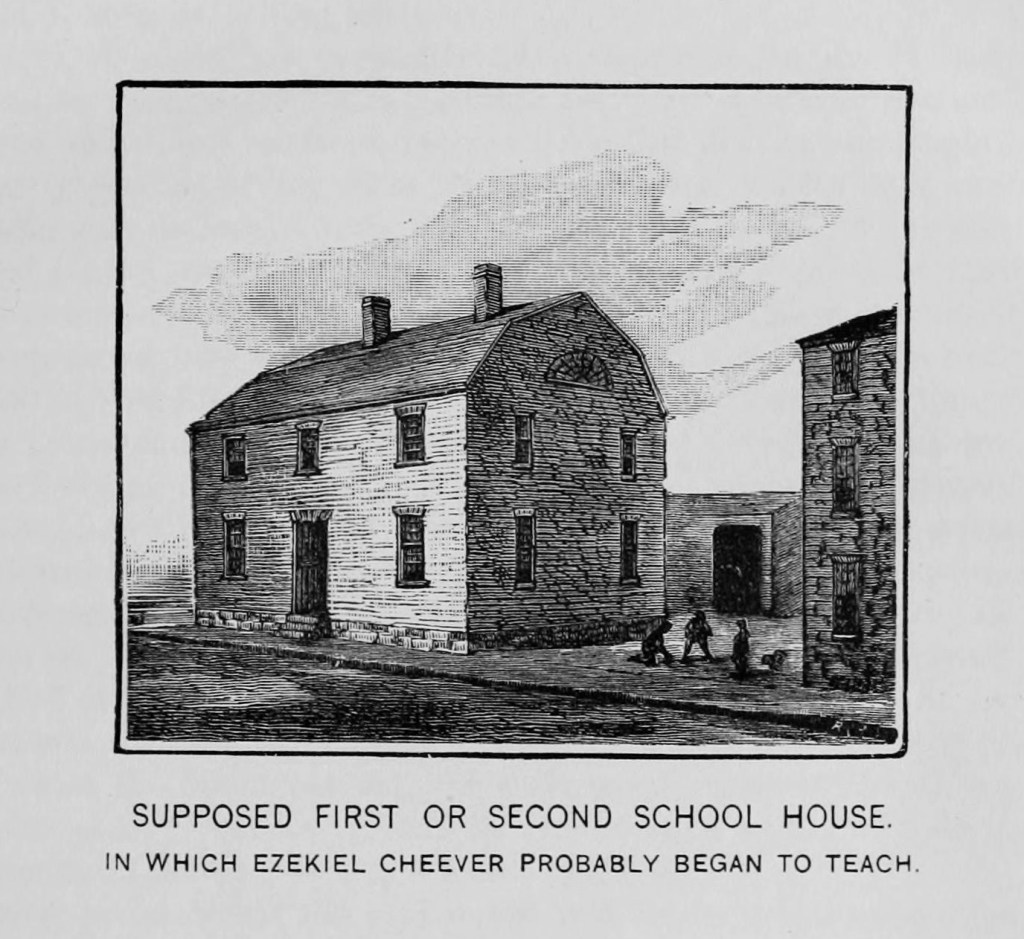

Established in 1635 on the principle that learning Latin was one of the key skills for success in higher education (certainly true in the 1600s), the Boston Latin School offered a roughly seven-year course based around mastering the ancient language of law and government, along with classes in other “humanities” areas.

The actual location of the school bounced around a bit. For the first decade of its existence, there was no dedicated schoolhouse. Classes were taught in the home of the headmaster, which at the time was located just beyond the southeastern edge of the Old Burying Ground. In 1645, a schoolhouse was built next to the headmaster’s home on the north side of what would eventually be called School Street. An updated building replaced or modified the original structure in 1704.

When it became known in 1745 that King’s Chapel would be totally re-constructed and expanded in the near future, the Boston Latin School moved across the street, and the 1704 building was demolished to make room for the much-bigger granite King’s Chapel.

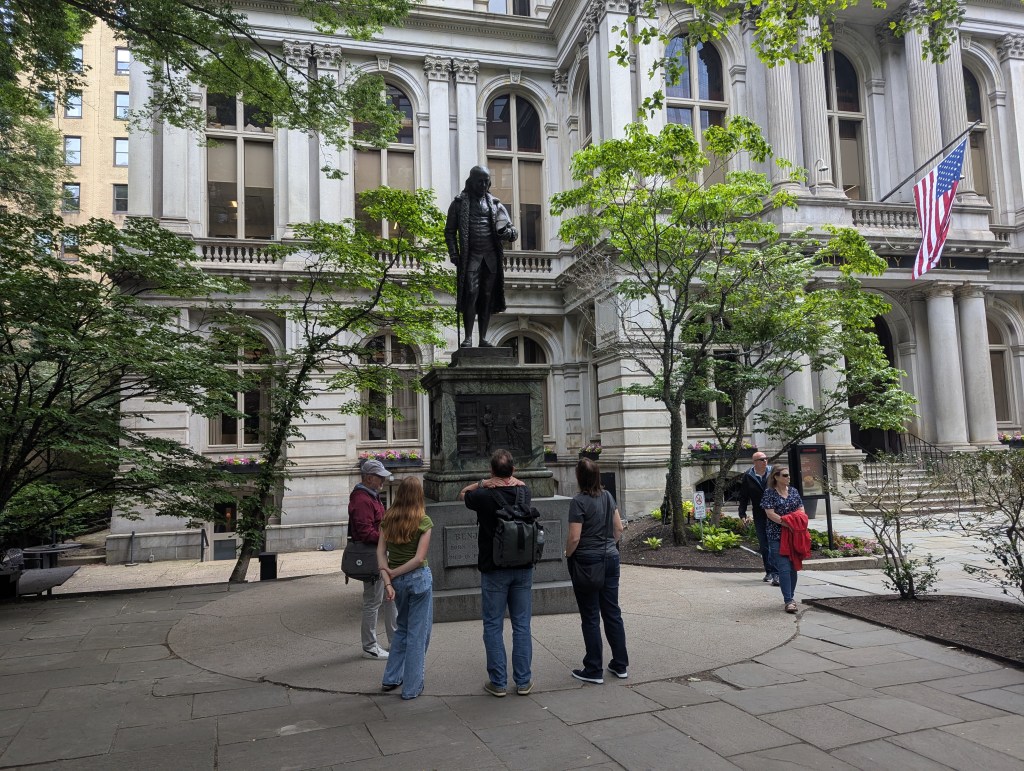

In theory, a new pupil would begin attendance around the age of 7 or 8, and complete a thorough grounding in the “classics” until deemed ready for university at 14 or 15. There was no formal diploma or graduation. In practice, very few students attended for the full seven years, and there was never any danger of the school having more students than it could handle, despite it being free. Benjamin Franklin attended for less than a year before he realized he hated everything about learning Latin. Typical of Boston’s one-sided attachment to Franklin, they erected a statue in honor of one of Boston Latin School’s quickest drop-outs on the former site of the school.

College educations started a lot sooner back then, and entry into institutes of higher learning was based on the recommendation of private tutors or academy instructors. (The concept of free public education beyond primary grades — i.e., “high school” — wasn’t really a thing until the late 1800s.) An ambitious American colonist of a certain social status was expected to be fully educated and established in his professional field by the age of twenty or so. Certainly that was the expectation for both Samuel Adams and John Hancock. Adams attended Boston Latin School in the 1730s, and the younger Hancock attended in the 1740s (he was probably a student when the school made the big move across School Street). Both ended up graduating from Harvard University (Adams at age 18 in 1740, Hancock at age 17 in 1754) and embarking on their exceptional careers (Adams, to be honest, a little erratically) at an age that would still be considered adolescence in the modern era.

The Boston Latin School existed in various forms on the south side of School Street until 1844, when it moved out of the area altogether. The original north side location (1635-1745) became the site of the Suffolk County Courthouse (1810-1841), which in turn became the site of the Old Boston City Hall, a beautiful Second Empire-style building that was completed in 1865, served as the seat of Boston’s city government until 1969, and is currently an upscale mixed-use facility that boasts a Ruth’s Chris Steak House. I am tempted to write more, but as it’s not officially part of the Freedom Trail, Old Boston City Hall falls outside the scope of this discussion. (As if Thomas Cranmer, the Archbishop of Canterbury in the mid-1500s, doesn’t fall outside the scope of this discussion, but what the hell, I follow my storytelling whims.)

The location of the original Boston Latin School is marked by the Benjamin Franklin statue in the forecourt of the former city hall, and a mosaic in the sidewalk designed by Lilli Ann Killen Rosenberg (1924-2011), who specialized in mosaic art for public spaces.

The mosaic is titled “City Carpet” and was installed in 1983. Roughly in the shape of a hopscotch diagram, it depicts images of children playing various playground games and an inscription commemorating the Boston Latin School. (Which is still in existence — now located at 78 Avenue Louis Pasteur, just south of Fenway Park, offering the high standards of a traditional New England prep school with the free admission of a public school. Good grades and a Boston residency are the qualifications for admittance, and yes, learning Latin remains a requirement for graduation.)

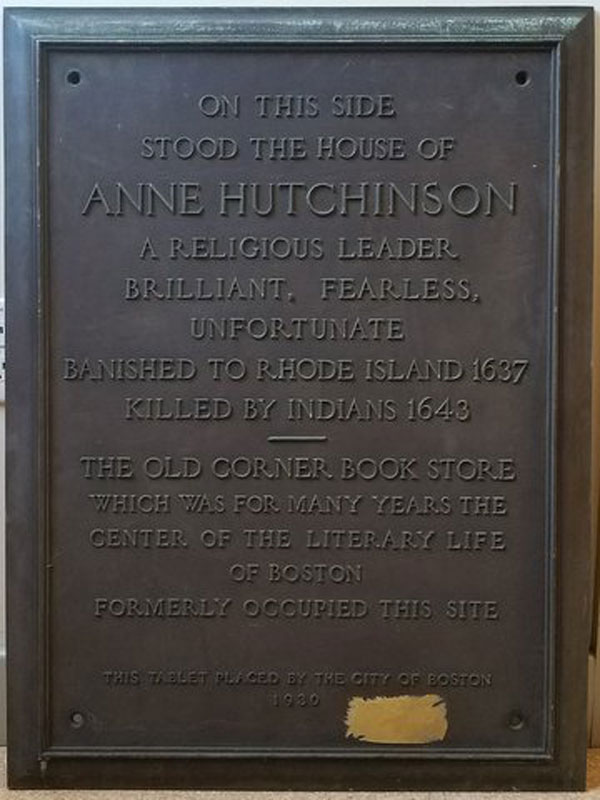

We proceeded to follow School Street until it intersected with Washington Street. Here we encountered #7, the Old Corner Bookstore. It isn’t now, and it wasn’t always, a bookstore. This corner lot, on a road that was once called Cornhill (long before the Washington who gave it its modern name was born), was considered one of the best plots of real estate in Puritan Boston. A fine, two-story wooden house was built there in the mid-1630s, and occupied by one William Hutchinson. Hutchinson was a wealthy textile merchant who was also a town councilman and member of Massachusetts’ General Court. Despite his prosperity and status, Governor John Winthrop described him as meek, a man of “weak parts” (oof!), and in the shadow of his opinionated wife, Anne.

The charismatic Anne Hutchinson — “of ready wit and bold spirit,” according to Winthrop — was definitely the dominant force in the household. She had borne fourteen children before leaving England for Massachusetts, eleven of whom survived to make the journey with her and William. She became a midwife and spent her days ministering to the sick and needy. Her frequent dispensing of spiritual advice led to her hosting a women’s Bible study group that was instantly popular. The First Church in Boston, a Congregationalist assembly that met just a few yards up Cornhill from the Hutchinson residence, was frequently ministered by Anne’s religious mentor, John Cotton. Cotton and Hutchinson became more and more critical of Puritan orthodoxy. Her post-church meetings began attracting curious men, many of whom found themselves nodding in agreement at her pronouncements. Even colonial governor Henry Vane, occupying the office during the few times Winthrop wasn’t, was known to be a huge A.H. fanboy. Hutchinson began pushing her controversial (for a Puritan) opinions even further, and often made showy point of stomping out of services ministered by those she disagreed with (followed by a retinue of devoted supporters). She soon found herself in hot water with the local authorities. She could out-debate any religious scholar, had an answer for everything, and her interpretations of Biblical teachings made a whole lot of sense to those who approached them with a bit of critical thinking.

Naturally, she had to go.

After a series of civil and church trials through 1637 and ‘38, Anne Hutchinson was banished from the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Luckily, she didn’t have to go alone. Her family went with her, along with dozens of followers, to settle on Roger Williams’ privately-owned Providence Plantations, just beyond Massachusetts’ southwest border. Williams was a fellow dissident and exile whose philosophy closely aligned with Hutchinson’s, and he welcomed her and her group to his territory after they had traveled almost a week on foot through snowy weather. Her trouble-making instincts never left her, however, and she got herself involved in a number of political imbroglios as the Providence Plantations and surrounding settlements began coalescing into the colony of Rhode Island (she is frequently credited as one of the colony’s founders). In 1641, the Massachusetts Bay Colony began making realistic threats about annexing Rhode Island. With her husband recently deceased, Anne decided the best thing to do was move out of English territory altogether to the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam (now New York City). Not even erstwhile ally Roger Williams was sorry to see her go, as she had been a handful. She and several of her now-adult offspring established a homestead in what is today the upper reaches of the Bronx (no one knows exactly where, except that it was somewhere within the boundaries of today’s Pelham Bay Park close to Split Rock). Back then, the Bronx was a different kind of dangerous wilderness, and Anne and most of her family were killed in an attack by the indiginous Siwanoy people in the summer of 1643.

Back to her old house on the corner…

Occupants came and went until 1708, when it was purchased by a Mr. Thomas Crease, a druggist by trade who peddled his medicines on the ground floor while living on the upper floors. (Have you ever seen the contents of an 18th-century apothecary kit? There’s one on display in the British Museum, and boy does it make you grateful you live in the modern era. I’ve often wondered what the dried skink is supposed to cure.)

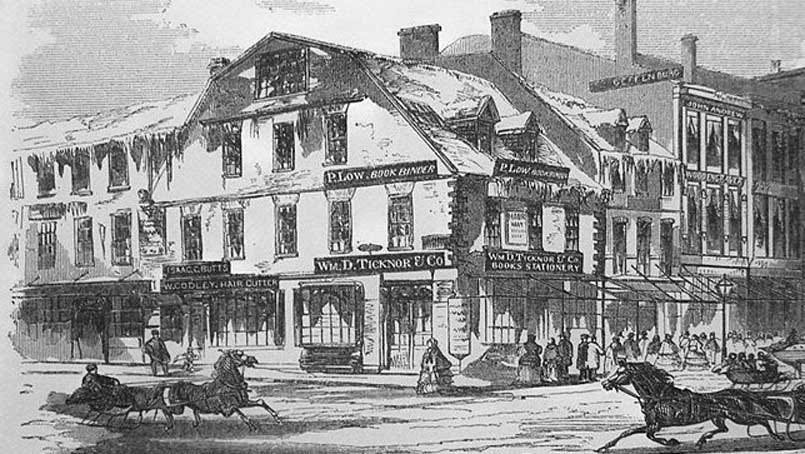

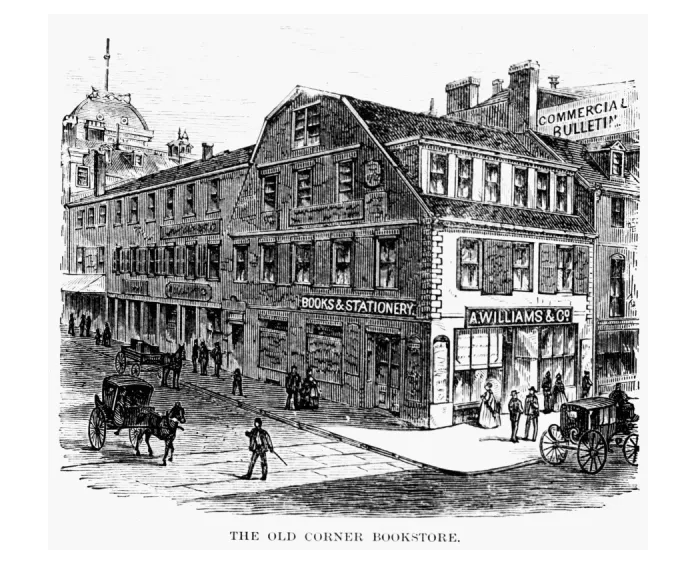

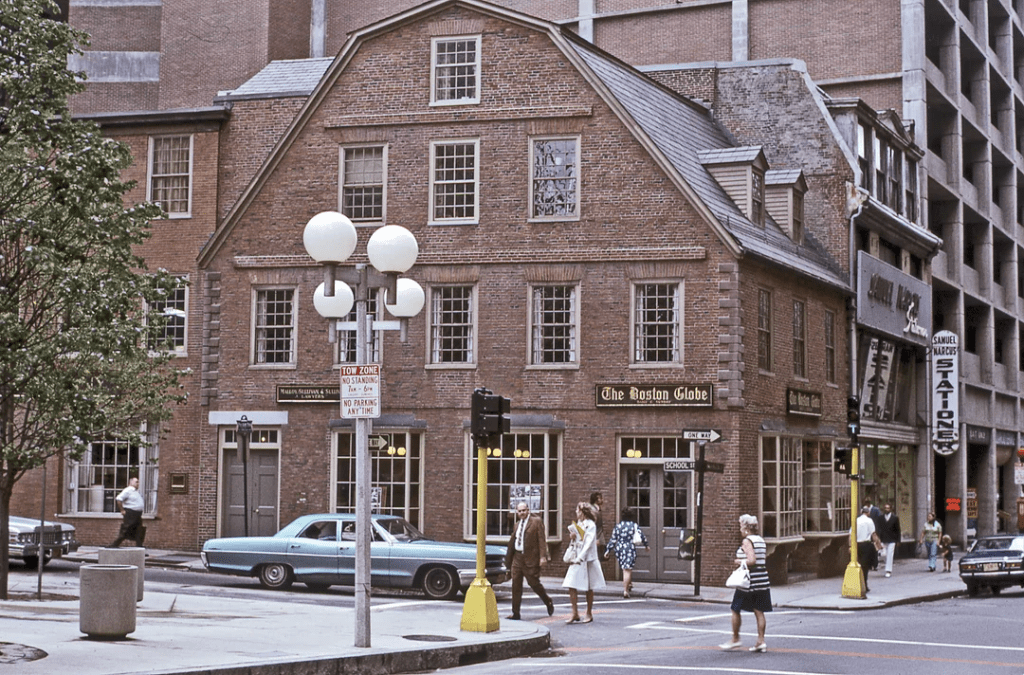

The Hutchinson/Crease building burned to the ground in 1711, during the first “Great Boston Fire” that also leveled the First Church and the First Town-House (to be replaced by the Old State House). Crease held onto the property, and a new brick structure was built on the lot in 1718. This is the Old Corner Bookstore that stands there today, and is one of the oldest brick buildings in Boston. (Subsequent “Great Boston Fires” in 1760 and 1862 would also leave their mark on the city, but miss this particular building.) It remained a pharmacy under various owners until its first recorded use as a book shop in 1828.

With a new address of 135 (now 283) Washington Street, the building hit its stride as a book shop when it was occupied by the firm of Ticknor and Fields for over thirty years in the mid-1800s. Not only did they sell books, they were also innovative publishers who invented the concept of author royalties, and published important works of the great New England writers of the era such as Emerson, Thoreau, Hawthorne, Longfellow, Stowe, Alcott, along with the American editions of the novels of Charles Dickens. Not only did the company publish and sell these works, the site itself became something of a literacy center and salon, where the authors would frequently drop by to talk shop with each other, their publishers, and their readers.

After the publishing firm moved locations in 1864, 135 (or 238) Washington Street passed through a number of owners, but remained associated with books and publishing through the end of the 1800s. Through the 1900s and early 2000s it has been a men’s clothing store, a cigar store, a pizza restaurant, and a jewelry store among many other establishments.

It was saved in the nick of time from demolition in 1960. A parking garage was planned to go there, but enough Bostonians came to their senses and rallied to prevent this. (The garage was moved just up the street and is visible in the pics below.) Its last stint as a book shop was from 1982 to 1997, when The Boston Globe newspaper owned it and used the site to sell travel books.

It is currently a Chipotle burrito restaurant. Maybe not its most prestigious use, but way better than a parking garage. The feisty Anne Hutchinson might have enjoyed debating “covenant of works” versus “covenant of grace” over an adobo chicken bowl on the site of her former residence.

We’ll meet her great-great-grandson Thomas Hutchinson soon enough.

(Didn’t we want to grab a bite at the steak house in Old City Hall? Or a burrito at the most historical Chipotle in the country? No, not yet. From setting out to find the Liberty Tree at the start of Part 1 of this series to admiring the Old Corner Bookstore here at the end of Part 3, about two hours of real time had passed for us. Don’t worry, I’ll be speeding things up as soon as we complete the Freedom Trail.)

SOURCES:

http://dirkdeklein.net/2018/01/18/the-kings-great-mater/

https://www.bpl.org/blogs/post/kings-chapel/

https://www.pilgrimhall.org/mary_chilton.htm

https://www.boston.gov/departments/archaeology/boston-latin-school

https://www.bls.org/apps/pages/index.jsp?uREC_ID=206116&type=d

https://www.arts.wa.gov/collection/artist-collection/?id=2251

https://smallstatebighistory.com/portsmouths-founding-mother-anne-hutchinson/

boshist.org/anne-marbury-hutchinson/

Freedom Trail Boston: Ultimate Tour & History Guide by Steve Gladstone

Henry VIII by Alison Weir

And good ol’ Wikipedia — the Lazy Researcher’s Friend