John Hancock was likely a smuggler. But so was everyone else in his line of work. To a Boston merchant, finding creative ways to evade the Navigation Acts was just good business.

The series of Navigation Acts that began being passed in 1651 required that all shipments to and from the American colonies had to be on British-owned ships, and cargos had to pass through an English port no matter where they were coming from or where they were going so they could have import duties paid directly to the British government, along with a variety of other restrictions designed to line British pockets.

It was a policy that was outrageously unfair to colonial merchants, but almost impossible to enforce effectively, and for much of the 1700s, Britain didn’t try particularly hard. As a result, tons of “illegal” untaxed goods sailed into Boston Harbor, technically making a criminal of one of our nation’s founders long before he joined the treasonous revolutionaries. (When the British government actually tried to get tough on import duties, the result was the Boston Tea Party, more on which anon.)

John Hancock’s father and grandfather were ministers. His father baptized the newborn future president John Adams in 1735. Hancock himself was born in 1737, and seemed destined to join the family trade. Those plans were derailed in 1744 when Hancock Senior dropped dead. Little John was sent to live with his uncle, Thomas Hancock. Hancock’s birth mother quickly re-married and vanished from his life, so Thomas’ wife Lydia became his beloved maternal figure.

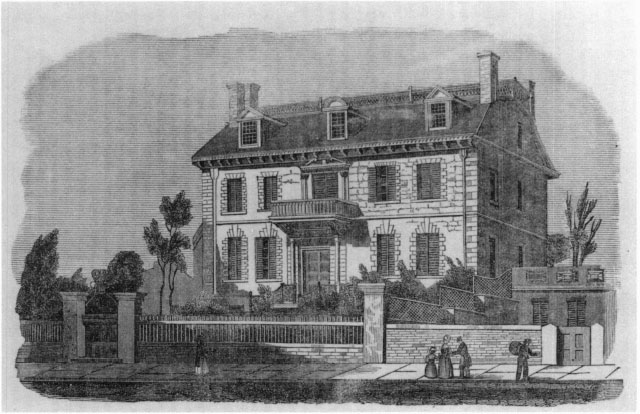

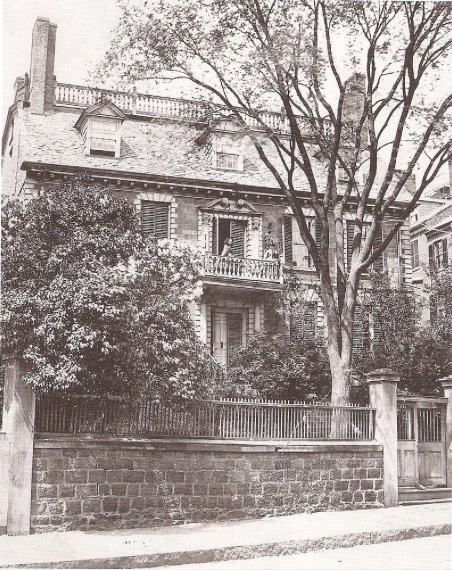

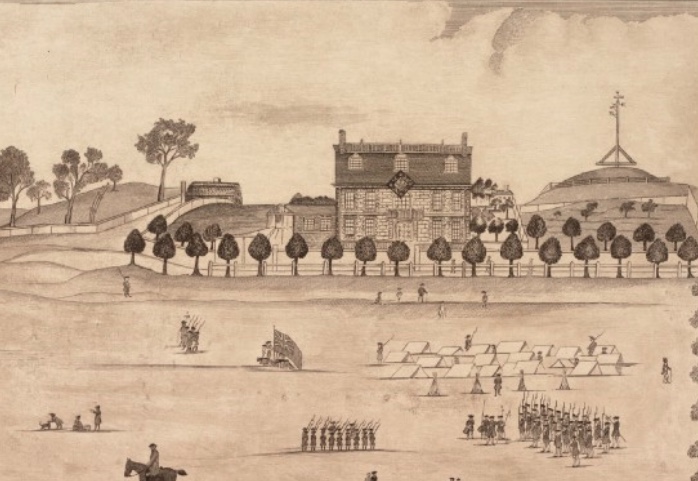

As a purveyor of “general merchandise,” Thomas Hancock had done quite well for himself. An early adopter of vertical integration, Thomas owned huge tracts of tree-filled land, a paper mill to turn the trees into paper, a bookbinding factory to make the paper into books, and a bookshop to sell the books, among many other interests. It was only natural that such a prosperous merchant should have a fine home, so in 1735, Thomas bought some land on the south slope of Beacon Hill next to the Common and began construction on what would be described as Boston’s most famous home — Hancock Manor, the first house built on that hill, which in those days was on the far edge of the city proper.

Two-and-a-half stories tall, the brown granite Georgian mansion sported three big dormer windows along the gambrel roof, a dozen main rooms, a dozen steps leading up to a broad front porch with a balcony above facing Beacon Street, and extensive gardens and orchards. The house had a commanding view of the city and the harbor. Thomas Hancock enjoyed his palatial estate for almost thirty years. When he died in 1764, he left all of his businesses — locks, stocks, and barrels — to nephew John. John had been working diligently for his uncle for the past decade, and had learned the import/export business inside and out. Aunt Lydia inherited Hancock Manor, but signed it over to John almost instantly with the understanding that she could continue to live there.

In one fell swoop, John Hancock was one of the wealthiest men in Massachusetts. He gave generously to the Boston community, covering the costs of the laying of paved walkways in the Common, the entire re-construction of the Brattle Street Church, and the free distribution of firewood to the poor during the winter months. His popularity gained him a place on both the town council and in the colonial assembly.

His deep pockets also funded the Sons of Liberty and their fight against British oppression. The savvy Samuel Adams took the political neophyte Hancock under his wing, knowing his local prominence as a successful businessman and his facility for using money to make more money could be very useful to the cause.

Adams and Hancock made an odd pair. The shabby Adams could usually be found in the taverns and down at the harbor in his threadbare coat, shaking hands, gathering news, making contacts and connections. The genteel, well-dressed Hancock preferred more elevated company, and many among his business associates and social circle were conservative Tories who may not have known there was a rebel in their midst. Odd couple or not, once the situation between Britain and the colonies turned violent, it did not take the British authorities in Massachusetts too long to single out the team of Adams and Hancock as the driving force of the incipient revolution.

In 1768, one of Hancock’s cargo ships, the Liberty (it was by now public knowledge where his political sympathies lie), was busted for smuggling. Try as they might, the British officials could not get the politically-motivated, trumped-up charges to stick, and the case was eventually dropped. But it galvanized Hancock against the British even more. To be clear, no official evidence of Hancock smuggling anything has ever come to light. But, c’mon…he was probably just really good at it…

Once I had located the former sites of the Liberty Tree and the Great Elm, it was time to begin our walk along the Freedom Trail. The Freedom Trail was conceived in 1951 by journalist William Schofield, who thought a pedestrian trail that linked important Revolutionary landmarks in the relatively compact central Boston area would be a great idea. Local civic leaders and historians agreed, and a route was established using 30 painted signs to guide the way. This system was a little befuddling for the typical tourist, so in 1958 an idiot-proof path was laid directly on the ground using red bricks. In 1972, the Trail was extended across the river into Charleston in order to include Bunker Hill and the USS Constitution. As of 2025, over four million people walk the Freedom Trail every year.

The Freedom Trail officially consists of sixteen sites:

1. Boston Common

2. The Massachusetts State House

3. Park Street Church

4. Granary Burying Ground

5. King’s Chapel and Burying Ground

6. Boston Latin School

7. Old Corner Bookstore

8. Old South Meeting House

9. Old State House

10. Boston Massacre Site

11. Faneuil Hall

12. Paul Revere House

13. Old North Church

14. Copp’s Hill Burying Ground

15. USS Constitution

16. Bunker Hill Monument

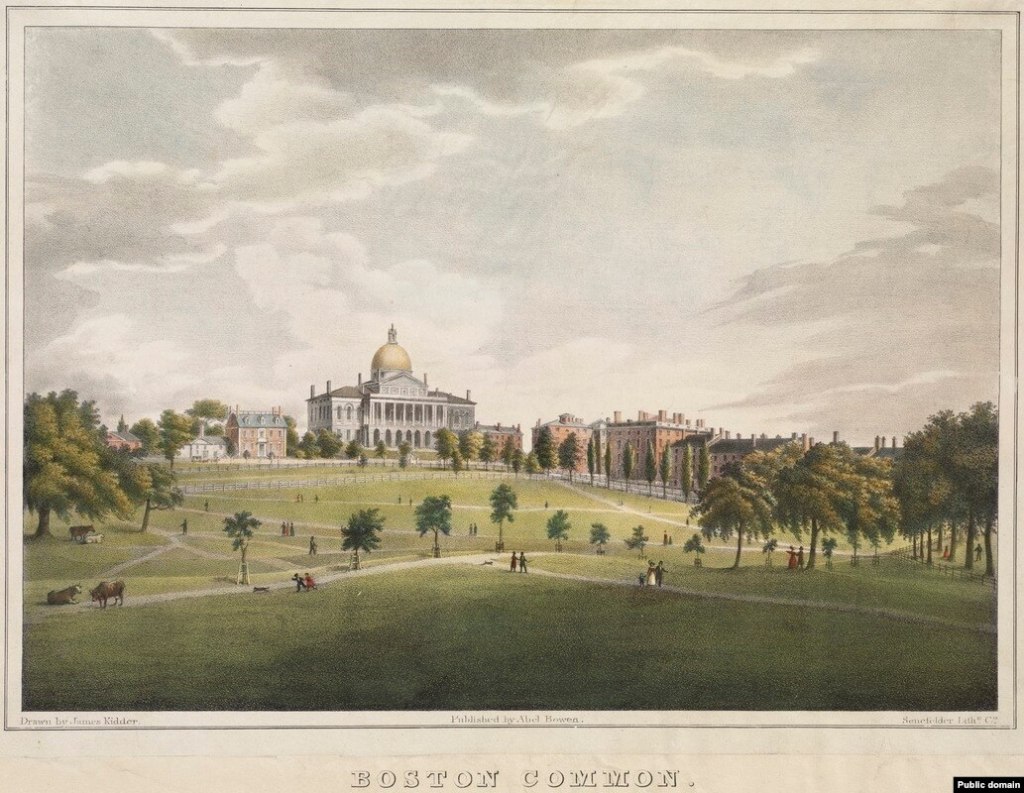

#1 Boston Common was already discussed in the previous entry, so we’ll move on to the second stop on the Trail, which was…

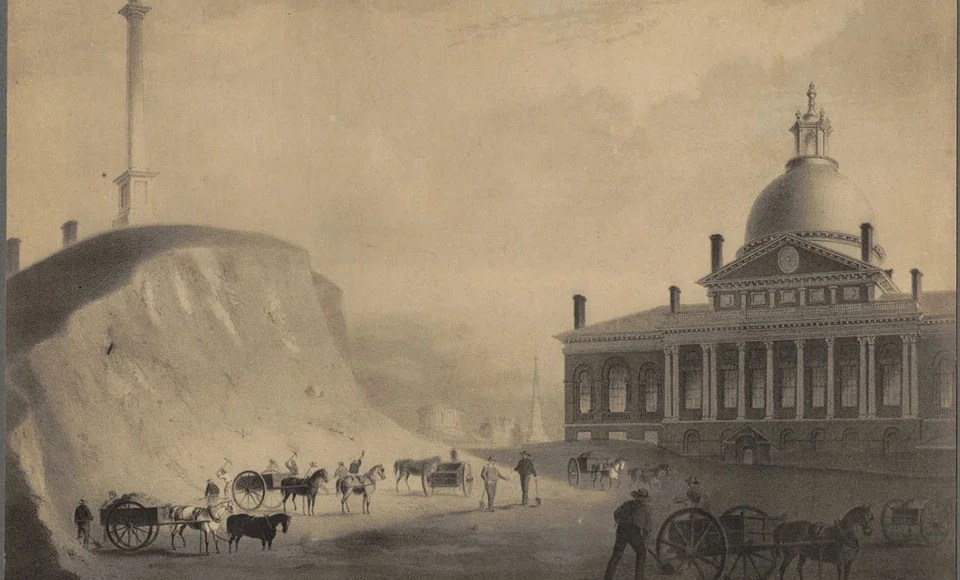

#2 The Massachusetts State House is just across Beacon Street from Boston Common. The parcel of land it was built on was mostly made up of Hancock Manor’s former cow pasture, sold off by Hancock’s wife in 1795 (Hancock himself had died two years earlier). Boston’s new young hotshot architect Charles Bulfinch was hired to design a grand new state capitol building to replace the too-small Old State House (more on that anon) where the Massachusetts assembly had been meeting since 1776. Bulfinch designed a red brick building in a Federal style, with an imposing central dome and white marble trim. It was right next door to Hancock Manor on the south slope of Beacon Hill, the summit of which rose up just behind them.

There were originally three hills. There was Mount Vernon a little to the west, and Mount Pemberton a little to the east, forming a triple-humped ridge. Calling them “mounts” was pretty aspirational — none of them were much over 130 feet in elevation. (Occupying British soldiers referred to Mount Vernon as “Mount Whoredom” for reasons that may not necessarily be the obvious ones.) The area was referred to by locals as the “Tri-mount” area, and the name lives on in nearby Tremont Street. In 1635, five years after the city of Boston was founded, the early settlers placed a wooden beacon on top of the taller central hill — Beacon Hill. The beacon was intended to warn the populace of any imminent danger, a kind of early civil defense signal.

Hancock Manor was forcibly evacuated when the British took over the city in 1775. Senior general Henry Clinton commandeered the high-status house as his headquarters. (To Hancock’s relief, the British commander was a fundamentally decent man and treated the property well during his unwelcome residency.) Hancock and his new wife, Dolly, were down in Philadelphia, where he had just been chosen as President of the Continental Congress. Elderly and frail Aunt Lydia went to stay with friends in Connecticut, where she died in April of 1776, a month after the British evacuated Boston, and just over two months before Hancock put his oversized signature on the Declaration of Independence.

Hancock’s daughter — Lydia — was born that fall but only lived ten months. It was a gloomy Hancock Manor that an ill and exhausted John returned to in November of 1777, having served in the Congress for well over two years, most of that time in the position of President, chairing meetings, writing letters, and raising funds. He gained new admirers, and at times alienated old friends, including Samuel Adams. Adams’ radical heart could not abide Hancock cozying up to the more conservative members of Congress in the months before the Declaration, but Hancock knew the political advantages of playing to both sides. His array of businesses were shuttered or sold at a loss during the Revolutionary War years. All in the service of managing a conflict that seemed unwinnable at this point. Far from the political newbie of the previous decade, Hancock was a true statesman now…

There was a brief period when the British army removed the beacon from its hill during their occupation, but it was restored and stayed put until a storm blew it down in 1789. By then it was decided old wooden beacons weren’t really an urgent need anymore. It was replaced on the summit by a memorial pillar topped by an eagle, also designed by Charles Bulfinch.

Construction on the Massachusetts State House was finished in 1798. The original wooden dome leaked, so in 1802 it was sheathed in copper provided by Paul Revere’s copper rolling factory. (It’s currently gilded in 23k gold leaf.) Not long after, Boston decided it was tired of being a semi-island, and a series of lengthy landfill projects began to bulk out Boston’s land area and attach it more firmly to the rest of Massachusetts. Much of the landfill came from leveling Boston’s low but numerous hills, including the Tri-mount. The process of whittling down Beacon Hill began in earnest in 1807 (leveling the other two had started a few years earlier), and was completed by 1828. The eagle pillar that once graced Beacon Hill’s lofty summit is now rather sadly plonked on level ground right behind the State House.

As we stood in front of the State House gates there was clearly a bit of elevation over street level. Beacon Hill is indeed still a hill, just not quite as noticeable.

No one goes in or out of the big main doors of the State House, with two exceptions — a visit from the U.S. president or a foreign head of state, or when a Massachusetts governor departs on their last day of office*. All legislators, support staff, and visitors have to use the…wait for it… Hooker Entrance.

The public entrance is in the east wing, and is fronted by an equestrian statue of Civil War general Joseph Hooker. Hooker was best known for being the general in command of the Union’s largest army, the Army of Potomac, for about fifteen minutes and botching their chances of victory at the Battle of Chancellorsville after being blasted into total incoherence by a too-close cannonball strike. (He should have turned over command to a subordinate, but refused, and everything went to hell.) Still, he was a “local boy made adequate” (born in Hadley, MA) who showed occasional flashes of competency at lower levels of command, so I suppose his statue in front of the east entrance to the Massachusetts State House is a kind of “well-at-least-you-tried-and-we’re-proud-of-you-anyway” participation trophy.**

We walked through the doorway proudly emblazoned with a “General Hooker Entrance” sign, giggling like Beavis & Butthead (and wondering if there was another, slightly smaller “Specialty Hooker Entrance” somewhere), through the security checkpoint, and into a rabbit warren of interconnected hallways. After a few wrong turns, we climbed a staircase into Doric Hall, the reception area for “social gatherings and official ceremonies,” according to the little fact sheet I picked up near the entrance. The name derives from two rows of Doric columns running down the center of the room. Among the other aspects of his life we’ve looked at, John Hancock was also Massachusetts’ first (1780-85) and third (1787-93) state governor.

So Hancock Manor became the Governor’s Mansion, where guests such as George Washington and various European dignitaries, including the Marquis de Lafayette, were lavishly entertained. While dealing with the Shays’ Rebellion crisis in January 1787, Governor Hancock suffered another personal loss — his nine-year-old son, also named John, died after sustaining a head injury while ice skating. He had no other children. And Hancock’s own health was declining. He had suffered from gout and related inflammations for years, and he was incapacitated at more and more frequent intervals during his second stint as governor. In his last public appearance he could neither speak nor stand. He spent his final days in seclusion in the home he had lived in since he was seven…

Governor Hancock died in office on October 8, 1793, and the lieutenant governor who took the reins was his old mentor and revolutionary accomplice Samuel Adams, who was present for the cornerstone-laying ceremony for the new State House in 1795.

A bronze bust of Hancock looked down on us from the west wall of Doric Hall.

Although it was built because the Old State House’s size was inadequate, the original Massachusetts State House occupied a remarkably narrow footprint. If you were to enter the front doors and walk a mere sixty-one feet, you would bump your face against the back wall. An extension was added in 1895 — Nurses’ Hall (in honor of Civil War nurses), and beyond that, the Memorial Hall, or Hall of Flags, where over 400 battle flags from various Massachusetts military units that have seen action from the Civil War to Vietnam are stored in climate-controlled vaults.

The ones on display are not the originals, but transparency replicas. As a supporter of proper historical preservation, I understand this, but as a tourist, it’s kind of disappointing not to be looking at the real thing. (A massive modern extension — the “Great Hall” — was added behind the Hall of Flags in 1990 to serve larger “official state functions.” It’s worth poking your head in for a few moments to admire the 351 flags representing every city and town in Massachusetts.

On the third floor, we find the chambers of the Massachusetts House of Representatives, the Massachusetts Senate, and the governor’s Executive Chamber. These are pretty much off-limits if you’re not part of an official tour and are just randomly wandering around. I managed to duck into the House of Representatives chamber by pretending to be on the tail end of an official tour to grab a quick picture of the Sacred Cod. The nearly five-foot carved wooden replica of an Atlantic codfish has been hanging above the Massachusetts legislature since at least 1784, and possibly earlier. It is a symbol representing the importance of the fishing industry to Massachusetts throughout its entire history. It is said (and impossible at this point to confirm) that the very first export from the colony of Massachusetts back to England was a shipment of cod.

The side hallways are lined with portraits of every Massachusetts governor, going all the way back to the first two colonial governors John Endecott and John Winthrop, who seemed to swap the office back and forth for almost twenty years. Endecott was a Puritan extremist who wondered if he could outlaw long hair on men and suggested that women wear veils in church, and preferred to govern from among his fruit orchards in Salem. (He was also responsible for the banishment of Quakers described in the previous entry.) Winthrop was a more reasonable moderate who threw himself into the founding and development of Boston, and purchased the land that came to be Boston Common for the community’s use.

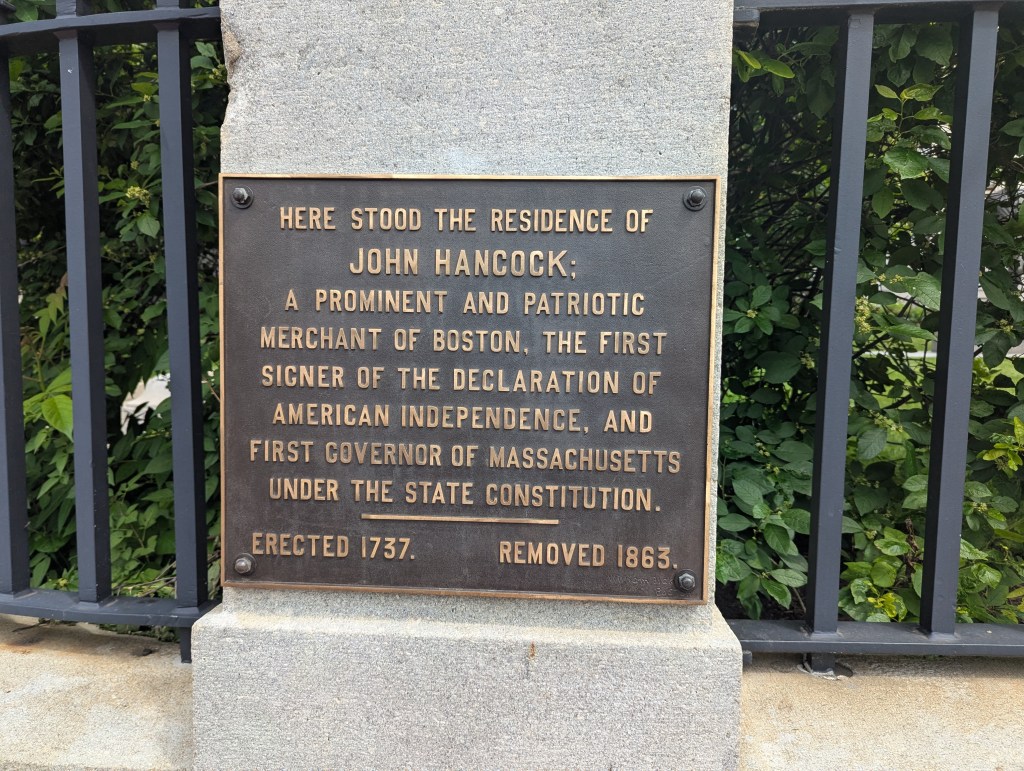

The widowed Dolly Hancock sold Hancock Manor to the couples’ nephew, John Hancock II, in 1819. He remained there until his death in 1859. Neither the City of Boston’s nor the Commonwealth of Massachusetts’ governments expressed any interest in preserving the house. It was sold at auction, and demolished in 1863.

The pair of townhouses that replaced it were also demolished in 1917 to make room for another expansion of the State House, a pair of white marble wings that contrast sharply with the brick of the central Bulfinch building.

Reeling from flag fatigue, we made our way back downstairs to the hallway maze, took a few more wrong turns, and finally emerged from the Hooker Entrance back onto Beacon Street. We wandered down the block to take a look at where Hancock Manor once stood.“My gardens all lie on the south side of a hill with the most beautiful ascent to the top,” wrote Thomas Hancock in the 1730s. “And it’s allowed on all hands [that] the kingdom of England don’t support so fine a prospect as I have of both land and water, neither do I intend to spare any cost or pains in making my gardens beautiful and profitable.”***

Now it’s all gone. Like the Liberty Tree and the Great Elm, “Boston’s most famous home” is now represented by another plaque. (And we’re far from finished with vanished buildings and their plaques.)

Directly across from the entrance to the Massachusetts State House is the Robert Gould Shaw Memorial. Shaw, the son of wealthy abolitionist parents who raised him to believe in racial equality, commanded the 54th Massachusetts regiment. The 54th Massachusetts was the first federally-authorized all-Black unit to be formed during the Civil War. Although the government was accepting of Black soldiers, they were not allowed to be officers, so it was Colonel Shaw who led them in the attack on South Carolina’s Fort Wagner in July of 1863, where Shaw and 77 of his men were killed. He was just 25 years old. The assault was a failure, but Shaw and the 54th became symbols of hope for an integrated post-Civil War society.

The memorial is a large relief sculpture in bronze created by Augustus Saint-Gaudens and unveiled in 1897. It depicts Shaw on horseback and several of his men marching down Beacon Street — passing this very spot, of course — just as they did on May 28, 1863 to ship out for the front lines in South Carolina.

If you’ve never seen the movie Glory, do so.

Doubling back from the State House, we passed through the eastern edge of the Common and crossed Park Street to find ourselves in front of…

#3 The Park Street Church was built in 1809 on the site of a former granary, and from that point until 1828 it was the tallest structure in America at a dizzying 217 feet. Its steeple is pretty prominent in the backgrounds of old paintings, engravings, and early photographs of the city. It had a strong and laudable association with abolitionist movement in the early 1800s, but ever since then it has carried the pungent, hyena-like odor of hardcore conservative evangelism. After admiring its graceful (I assume) red brick exterior and peering up at the steeple for a few minutes, we moved a few yards down Tremont Street to the church’s much more fascinating (to me at least, who doesn’t know much about architecture nor care much for religion) neighbor…

“No yard here has given rest to the mortal remains of more distinguished persons than this.” — Nathaniel Broadstreet Shurtleff, 1871

#4 The Granary Burying Ground is nestled right against the Park Street Church. Originally called the South Burying Ground, this was the third graveyard established in Boston dating from 1660. (Relax, we’ll get to the first two.) It was once part of Boston Common, which was slightly bigger in the 1600s. The ground being community property, two public buildings were erected next to it — a combination jail/workhouse and a 12,000-bushel granary. The name of the graveyard was changed to the Granary Burying Ground to make its location a little clearer.

There are 2,345 marked gravestones there, but it is likely more than 5,000 bodies (one estimate goes as high as 8,000) are interred somewhere in the two-acre site. A grave in a relatively small burying ground from the 17th century rarely contained only one body. They would stack as many as five or six, sometimes more, on top of each other, and only occasionally would the grave marker reflect who was actually in the grave. It’s why you usually have to walk up at least a few steps from street level to enter these old boneyards. Those bodies are piled high. The perimeter of the site is ringed with tombs and vaults, several of which have been lost, forgotten, or built over.

You will not see any crosses or angels or figures of Jesus here. The Puritans established this burying ground and their influence lingered even as Boston’s populace grew more diverse, and the Puritans did not like religious icons or imagery. The most common image on grave markers you’ll find here are the “death’s head,” a skull with wings on either side, widely used in the 1600s and early 1700s. Graves from a slightly later period softened the image to a winged cherub’s face, and later still they would use a “willow and urn” motif.

Speaking of grave markers, the tombstones were originally scattered haphazardly throughout the area. In the 1800s, to better reflect “19th century aesthetics,” and to allow space for pathways and the the newly-invented mechanical lawnmower, all the stones were re-arranged into neat parallel rows. This was done with little regard to where the bodies they were supposed to mark actually were. One would hope they were somewhere in the general vicinity, otherwise what’s the point of even having a tombstone? And it wasn’t always headstones. Sometimes footstones were used instead, or a six-foot long “table stone” if your family had the coin.

The first thing you notice upon entering the gate is a twenty-one-foot high granite obelisk with the name FRANKLIN prominently marked on it in the dead (pardon the expression) center of the property. No one wants a complete stranger walking up and correcting them, so I let the chattering ignoramuses (and there were many) who did not bother to read further on the monument beyond the last name to continue to believe this was the tomb of Benjamin Franklin. Franklin was born in Boston, but skipped town at age 17, never to return. No, this monument, erected in 1827, was funded by the Boston citizenry to honor Benjamin Franklin’s parents, who are indeed buried somewhere around here.

The engraving on their original gravestone had worn away, a common fate for carvings on slate or marble, so the people of Boston decided to splurge on an obelisk. Boston seems very proud of Franklin, despite the fact he wanted nothing to do with the place and is much more closely associated with Philadelphia, where he lived most of his life and is, in fact, buried.

From in front of the honored graves of Josiah and Abiah Franklin, pivot to the left and walk straight ahead until you almost hit the side of the Park Street Church. John Hancock is (was?) buried here. What actually became of his body is something of a mystery. Some say he was spirited away by graverobbers who assumed the wealthy Hancock was buried wearing valuable jewelry. Another story said the robbers wanted the right hand that scrawled that iconic signature. A more reliable source states that Hancock was originally placed in a wall tomb hard up against the church. Supposedly, in the 1860s this whole row of tombs was removed as part of a renovation to the church and to allow better lighting into the basements of the nearby structures on Park Street. The remains in the tombs were re-located as instructed by the deceased person’s descendants. For those that had no living descendants, such as Hancock…who knows? They may have been re-buried nearby, or disposed of in any number of random ways, because people in the 1860s had bigger things to worry about than a pile of moldering bones, no matter who they belonged to.

Any one of these stories may be true, or none of them. What is true is that there was no marker for Hancock for who knows how many decades, and it’s pretty damn iffy as to whether his mortal remains are even there at all. So this rather phallic pillar was erected (heh heh) in 1895 to make up for all of that. The pillar is topped with a carving of a hand and a trio of chickens. Get it? Hand + Cocks. Hancock. (I’m glad they went with chickens.) Just remember when you’re visiting this monument to pay your respects, there may be no corpse at all under that giant penis, or maybe it’s forty feet away…or maybe it’s there and just missing its right hand. (After everything in this paragraph, I’ll leave you to assemble your own masturbation joke.)

Going clockwise from here around the outer edge, you come to the grave of Paul Revere (more on him anon). There are actually two markers here, a very small and modest original, and a more elaborate marble one erected later.

Of the five original delegates from Massachusetts to the Second Continental Congress — the gathering of esteemed colonial representatives that voted for independence**** — you’ve probably heard of four of them: Future president John Adams, and future Massachusetts governors John Hancock, Samuel Adams, and Eldbridge Gerry (also a future vice-president under Madison, and where we get the term “gerrymander”). Then there’s poor, obscure Robert Treat Paine. He never got to be president, or have a beer named after him, or have his name be slang for a signature or a politically shady way of mapping congressional districts. Paine had to be content with being a signer of the Declaration of Independence, Massachusetts’ first Attorney General, and a justice on the Massachusetts State Supreme Court. Anyway, he kicked the bucket in 1814, and he’s here now, shoved into a tomb in the northern wall almost directly opposite what may or may not be Hancock’s grave. (“Northern” wall is an approximation since everything in this part of Boston is kind of on a slanted angle that plays hell with one’s orientation. Northeastern wall, maybe?)

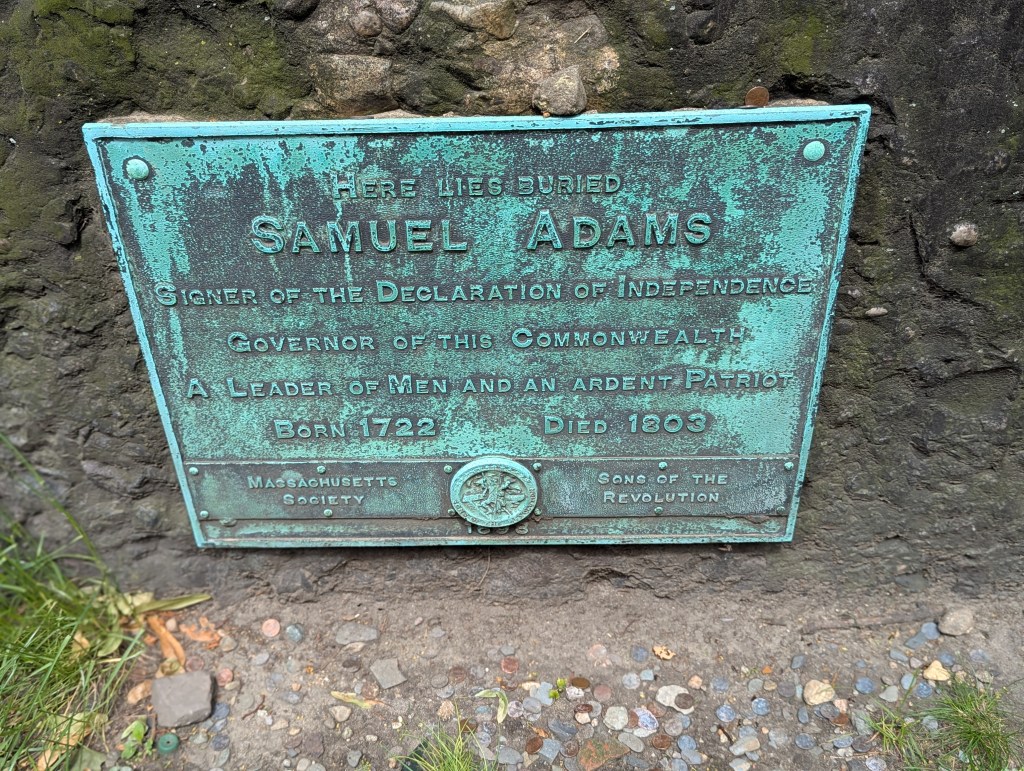

Coming around towards the entrance again, you’ll find the grave of Samuel Adams. Adams is sometimes referred to as the “Father of the American Revolution” for his leading role in the Boston protest movements of the 1760s and early 1770s. After signing the Declaration in 1776, like many of his fellow revolutionaries he dedicated himself to state politics. He mended his strained relationship with Hancock in the 1780s, and completed Hancock’s final term as governor. He was elected for three terms of his own (a term for a Massachusetts governor was only a single year back then), and retired in 1797. He died in 1803, and is (supposedly) buried directly acorss Tremont Street from a bar, the Beantown Pub. I later kicked myself for not having a cold Sam Adams across the street from another cold Sam Adams.

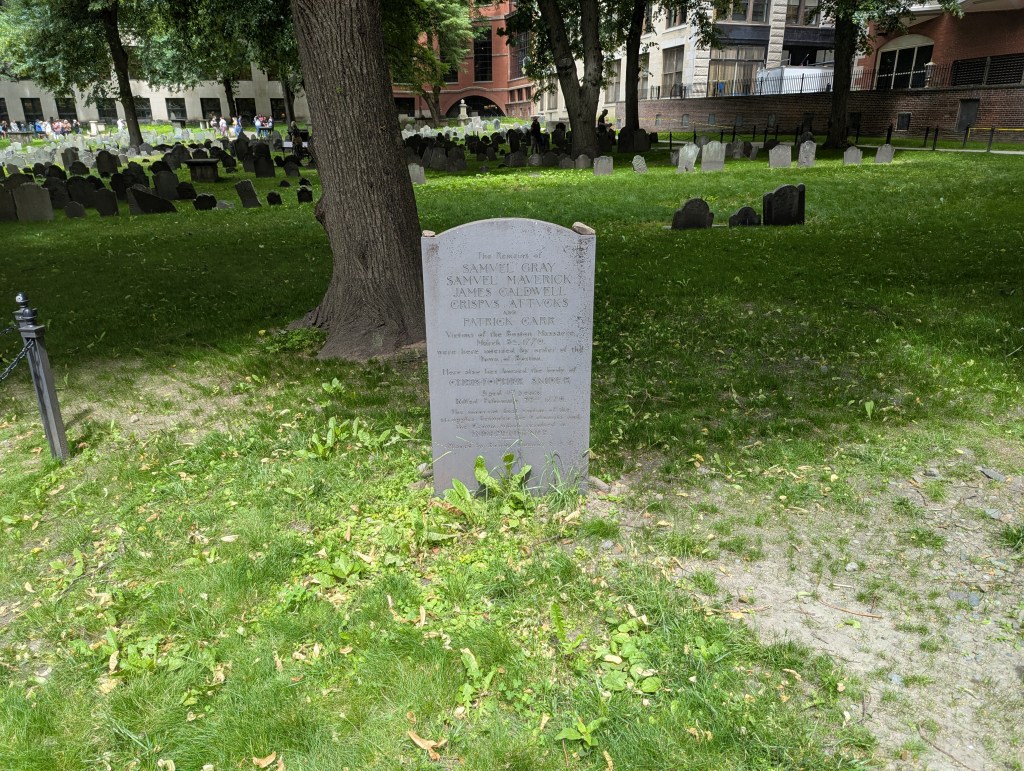

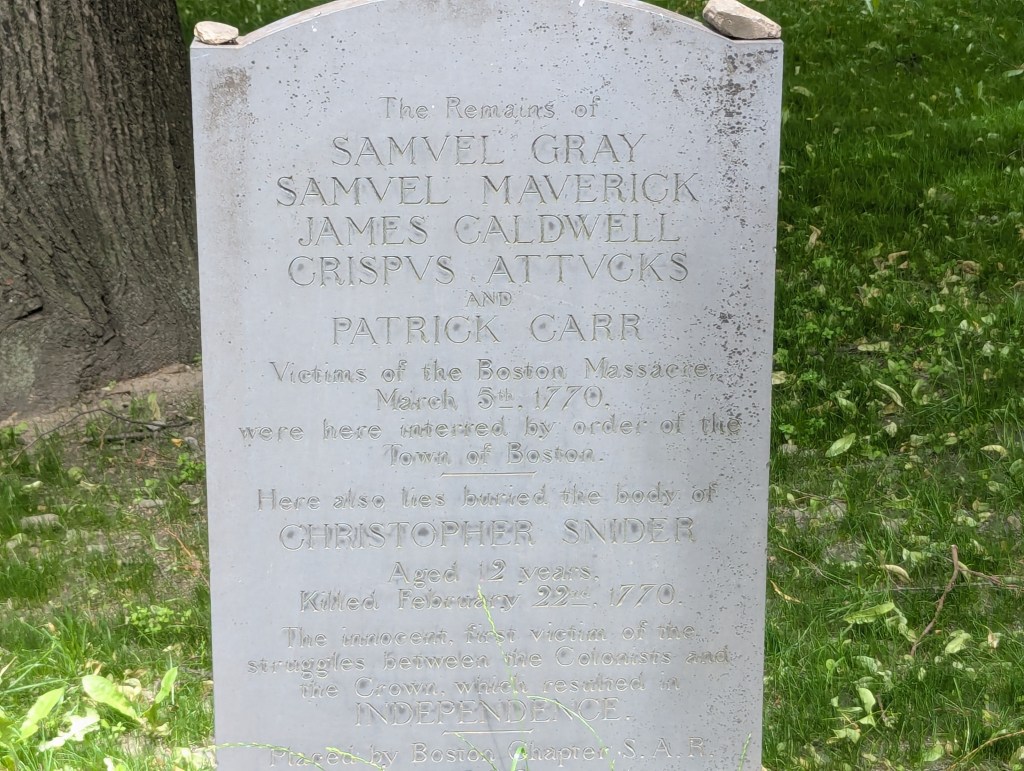

If you’ve been following the clockwise pattern, one of the last notable burial sites you’ll come across is the common grave of the five fatalities of the Boston Massacre: Samuel Gray, Samuel Maverick, James Caldwell, Crispus Attucks, and Patrick Carr. Also interred here is 11-year-old Christopher Seider who had been killed on February 22, 1770, eleven days before the Boston Massacre. He was among the crowd (mostly rowdy youngsters) who were protesting a Loyalist shopowner that was refusing to go along with the current colonial boycott. In an attempt to break up the near-riot, customs officer Ebenezer Richardson fired his musket (filled with “swan shot,” pea-sized lead balls) from an upstairs window into the mob, striking Seider in the arm and chest. He died later that night. His funeral was paid for by Samuel Adams and attended by over 2,000 people.

When the Boston Massacre occurred soon after, the dirt in Sieder’s grave was still loose, and the connection between the fatalities was an unmissable bit of symbolism and anti-British propaganda, so the five Massacre victims were added into, or next to, Seider’s grave. (More on the Boston Massacre anon.*****) Richardson was initially found guilty of murder in a Massachusetts colonial court, but pardoned by royal decree (it was self-defense, of course, despite the fact he was indoors and on the second floor firing into a crowd on the street) and reassigned to another department in the customs service.

Christopher Seider is sometimes referred to as the first fatality of the American Revolution. You would think they could have spelled his name right.

Other burials here include first colonial governor John Endecott (interred in Tomb #189, which is currently unmarked and no one seems to have any idea where it is), James Otis (an early proponent of colonial rights and mentor to Samuel Adams, who died after being struck by lightning), James Bowdoin, second governor of Massachusetts in between Hancock’s two stints, and Increase Sumner, the fifth governor of Massachusetts after Hancock, Bowdoin, and Adams.

The Freedom Trail journey continues in the next entry, where we visit another burying ground and at least two more non-existent buildings.

* A third reason to use the big front doors was when a Massachusetts regimental battle flag returned from a war. Nowadays, all regimental flags are sent directly to Washington, D.C.

** Hooker has his defenders — click this link for a fascinating read.

*** Spelling & punctuation modernized.

**** As opposed to the First Continental Congress which didn’t do squat.

***** I really struggled over whether I should present all of this in the order we experienced it on our trip, or the chronological order in which the events I’m relating happened historically. I went with the former, trusting the reader to mentally jump back and forth in time with me. For example, although we’ve examined their final resting places, we haven’t heard the last of Hancock or Adams by a damn sight.

(I know past a certain point you’re supposed to switch from asterisks to crosses or other symbols for footnotes, but it’s not immediately apparent where to find them here on WordPress. I suppose I could look it up, but at this point I’m pretty tired of looking things up.)

SOURCES:

https://americanaristocracy.com/houses/hancock-manor

https://www.nps.gov/places/beacon-hill.htm

https://www.sec.state.ma.us/divisions/mhc/archaeology/exhibits/mill-pond.htm

https://www.boston.gov/cemeteries/granary-burying-ground

https://www.endecottendicott.com/buriel

https://www.celebrateboston.com/sites/granary-burying-ground-faqs.htm

https://alphahistory.com/americanrevolution/report-death-christopher-seider-1770

Freedom Trail Boston: Ultimate Tour & History Guide by Steve Gladstone

The Baron of Beacon Hill: A Biography of John Hancock by William M. Fowler

Boston in the American Revolution: A Town Versus an Empire by Brooke Barbier

Beacon Hill, Back Bay, and the Building of Boston’s Golden Age by Ted Clarke

A Topographical and Historical Description of Boston by Nathaniel Broadstreet Shurtleff

The fact sheet provided by the Massachusetts State House (uncredited)

And good ol’ Wikipedia — the Lazy Researcher’s Friend