We’ll start this off in a logical fashion: by discussing two elm trees that no longer exist.

Actually, let’s back up a bit. When I last left you, I had been forced to abandon my trip to Boston in the summer of 2024 due to a mild case of passing out on a departing airliner, which was due in turn to a less-than-mild case of influenza (which I swear I had no idea I had). We got as far east from California as Gate B43 at Denver International Airport.

Since then, I got vaxxed to the gills for both COVID and flu. I always dutifully got my COVID vaccine since it was introduced because I am a good citizen and a believer in basic science, and also pretty dubious about the efficacy of location-tracking nanobots being injected into my bloodstream. My flu vaccination was always a little more hit or miss (mostly miss) because — as I figured it — “I never get the flu.” Well, lesson learned. It’s the double jab for me every autumn from now on.

And now, here I was, striding across Boston Common on an overcast morning the following summer, eager to see a couple of vanished elms. Thus began my week of, as my wife put it, “taking pictures of plaques.”

The first place I was looking for was at the corner of Washington and Boylston, right where Boylston turns into Essex, on the northern edge of modern Boston’s Chinatown. There was, naturally, a Dunkin’ Donuts on the opposite corner. (What you’ve heard is true. Boston is positively infested with Dunkin’ Donuts. The next nearest one was literally 300 paces away.)

As I approached, I tried to picture what this intersection must have looked like 260 years ago. Three dirt roads known as “Frog Lane,” “Essex Street,” and “Orange Street” converged into an open space known as Hanover Square. The Chase and Speakman distillery was nearby. This was the old “South End” neighborhood, respectably middle-class. There would certainly be no Dunkin’ Donuts. Hanover Square was the site of several large elms, said to have been planted in 1646. The elms were so distinctive they were used as a landmark by people guiding newcomers into the city (eg., “turn right at the big elm trees”).

One elm, a little bigger and taller than the rest, grew in the front yard of bookbinder and church deacon John Elliott (1692-1771), who owned the house directly across the street from the distillery…

Nowadays, the streets are very paved and very busy. Orange Street eventually became Washington Street, and Frog Lane became Boylston Street. The house and distillery vanished around two centuries ago, the modern South End moved further south, and now you’re only a few yards in multiple directions from a half-decent donut and incredibly shitty coffee. It was right here that the Liberty Tree once stood, and where the first quiet rumblings of what grew into the American Revolution were heard.

1765. The British treasury had been running on fumes since the end of the Seven Years’ War (yet another installment of the British National Pastime — going to war with France) two years prior. Since a big chunk of that war was to protect their colonial holdings in North America (and by implication, the colonists themselves) from the predations of the French army and their “savage” Native American allies, King George III and his Parliament thought it only fair that the American colonists pay their proper share for their own protection, which included a force of 10,000 British soldiers stationed on American soil from Georgia to New Hampshire. So they passed the Stamp Act in March of 1765, which imposed a small tax on paper goods sold in the colonies. The proof of payment of said tax would be an inked revenue stamp. It would go into effect that November.

The colonists and the royal government did not see eye-to-eye on this matter, to say the least. The Americans couldn’t give a toss about a handful of French soldiers in ramshackle little forts hundreds of miles over the Appalachians in the Ohio River valley. No, the colonists saw this as the Parliament picking their pockets to gain funds to keep an unwelcome military force in their midst, and to do god-knows-what else across their expanding global empire. It was pointed out to them that folks in Britain had been paying the exact same tax at a much higher rate for over fifty years. The colonists retorted (in the form of letters and petitions) that at least people living in Britain had some nominal say in how the revenue was spent, via their representatives in Parliament. American colonists had no such representation. They paid the necessary taxes raised by their colonial assemblies, who saw to it that the revenue was re-invested in, and served the needs of, that colony and that colony only.

As petty and stubborn as the American response to the first direct tax levied on them by their distant parent government was (it was only a few cents, after all, and the colonists did benefit indirectly from the British victory in the Seven Years’ War), it was definitely a principled response. And people started getting riled up. In Boston, especially.

Knowing myself as not much of a boat-rocker, nor a holder of many strong opinions that don’t involve classic rock, it pains me to acknowledge that I probably would have been one of those colonists saying “C’mon, guys, let’s just pay the damn tax and get on with our lives.”

A small group of Boston businessmen – “the Loyal Nine*” — began meeting clandestinely at the office of the Boston Gazette, and more notably, at the Chase and Speakman distillery, owned or co-owned by Loyal Nine members Benjamin Edes and Thomas Chase, respectively. The goal of the Loyal Nine was to prevent the Stamp Act from taking effect. They first plastered the streets of Boston with pamphlets and handbills, then decided to take it a step further.

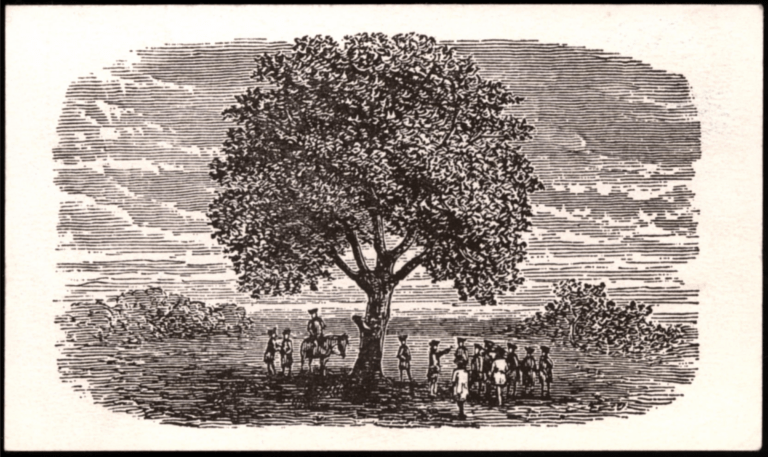

On the morning of August 14, 1765, local passersby noticed several effigies hanging from one of the limbs of Deacon Elliott’s huge tree, the most prominent of which was emblazoned with the initials “A.O.” This was clearly meant to represent Andrew Oliver, the official stamp tax collector of Boston. Word spread. A crowd gathered. Speeches were made. Passions were stoked. The crowd was an angry mob by sundown (possibly fueled by rum punch provided by the distillery), and marched off to ransack both Oliver’s home and office. The first protest by Americans against British “tyranny” ended with Oliver barely escaping with his life. Three days later, Oliver was practically frog-marched to the suddenly-signifigant tree in Hanover Square, and forced to publicly resign his position in front of a cheering crowd.

The elm was referred to as the “Tree of Liberty” in a Boston newspaper the following month, and went by variations of that name for the next decade. It was the staging area for all Boston protests for the duration of the Stamp Act crisis. It was frequently covered with notes, flags, and streamers. A flagpole was installed next to it to summon meetings of the Sons of Liberty. How complicit the elderly Deacon Elliott was with the use of his tree for these purposes is unknown. He has no known association with the Loyal Nine or the later Sons of Liberty. Some of its massive branches may have simply overhung a public pathway. But the fact that it was used as a meeting place so frequently, and was often heavily decorated (and Elliott was known to rub shoulders publicly with local anti-royalists — “whigs**”), serve as indicators that Elliott probably sympathized with the cause.

By the start of 1766, the Loyal Nine were folded into the much larger and better organized colonial protest group called the Sons of Liberty, and the term “loyal” was co-opted by supporters of the crown (“Loyalists”). The Sons of Liberty originated in New York, but soon had chapters throughout the colonies. The Boston chapter was established mainly by a newly-elected member of the Massachusetts colonial assembly, Samuel Adams. Adams had left a string of failed businesses in his wake, including the brewery that would (much) later be revived under his name. In the mid-1760s, he finally discovered his true talent: political agitation. Adams was a first-class pot-stirrer, and quite good at getting people on his side. A close associate of the Loyal Nine, but never an official member, it has been widely theorized that Adams was the mastermind behind all of their actions. There is no credible proof of this, other than the fact that the Loyal Nine were often viewed by later historians as run-of-the-mill merchants and artisans (and one ship captain) with little imagination, no previously demonstrated flair for inflammatory writing, nor any real skill at political organization. Still, never underestimate wealthy businessmen pissed off about paying taxes.

Under pressure from British merchants who were feeling the pinch from colonial boycotts of their goods, Parliament repealed the Stamp Act in February of 1766. It had never really been enforced. The Sons of Liberty called it a major victory, but before long there was more to be pissed off about (Townshend Acts, etc.), and meetings under the Liberty Tree continued.

Lots of stuff happened in Boston and around the Liberty Tree between 1766 and 1775, much of it none too pretty. The Quartering Act, the Boston Massacre, the Boston Tea Party and subsequent Intolerable Acts all served to further alienate the colonists from the mother country. In January 1774, an angry mob pulled a customs officer, John Malcolm, from his home in Boston’s North End. He was beaten with sticks, stripped of his clothes, and tarred and feathered. Tarring and feathering was the painfully humiliating ritual of coating a victim’s bare flesh with hot tar (causing second- or third-degree burns), then dumping chicken feathers over the sticky surface. It was a punishment more talked about than actually performed, but it did happen from time to time, perhaps no instance more horrific than this one. Malcolm was paraded in a cart to the Liberty Tree, forced to denounce the royal governor (which he refused to do), then had tea dumped down his throat in a lengthy series of sardonic “toasts” to every British politician the mob leaders could think of. Severely beaten, burned, hypothermic (Boston Harbor had completely frozen solid that week), probably vomiting tea and blood, Malcolm was paraded for several more laps around the city before he broke down and denounced the British government. At which point, he was dumped in front of his house, barely alive, with a long recovery ahead of him. (To be fair, Malcolm was well-known as the North End’s resident asshole — every neighborhood seems to have one — and this whole incident stemmed from him loudly threatening to beat a child sledding in front of his house with his walking stick, but still…) (And who brought all the tea? It reminds me of the hood scene in Django Unchained. Someone’s wife spent a whole afternoon brewing up gallons of tea for this awful purpose.)

Samuel Adams was careful never to authorize or condone violence in any action he had a direct hand in. But sometimes he turned a blind eye, and sometimes the rowdier elements of the Sons of Liberty were beyond his control. Some SoL’ers were undoubtedly involved that night. “It had been a brutal, even obscene display of violence,” wrote historian Nathaniel Philbrick. “But the people of Boston had spoken.” The crowd numbered over a thousand by time the horrific parade was over. The scene was repeated with other victims, perhaps less brutally and flamboyantly, frequently enough that it earned a name — “the Tree Ordeal.”

By the summer of 1775, Boston was an armed camp, an occupied city. British redcoats seemed to outnumber civilians, who mostly huddled in their homes, or moved away if they could. The inevitable finally came to pass. On August 31, 1775, the Liberty Tree was chopped down by a group of jeering British soldiers, aided by local Loyalists. It was reported that the tree yielded fourteen cords of firewood. The stump remained visible until at least 1830 or so, when it finally vanished under new urbanization. (For a while, patriotic citizens stuck a flagpole on it and called it the “Liberty Stump,” but everyone agreed this was a little sad, and the practice was abandoned.)

In 1850, a large brick building was erected at 630 Washington Street, across the intersection from the Liberty Tree site. A painted, bas-relief wooden plaque commemorating the tree was installed on an exterior wall three stories up, but this soon grew grimy and neglected, sometimes even obscured by tacky business signage. The area went into decline, and became Boston’s “skid row” by the mid-20th century.

In the 1960s and 70s, the intersection was the center of Boston’s red-light district known as the “Combat Zone.” Right where the first American protest against British policies began, you could indulge any number of your erotic desires in the string of adult bookstores, strip clubs, and porno theaters lining Washington and Boylston Streets. Male and female prostitutes plied their trade right where a tarred and feathered John Malcolm drank his forced “toasts.” (In the 1970s, you could probably have found some tar and feathers for yourself, if that was your kink.) Thanks to re-zoning laws, increased police presence, and the withdrawal of most adult entertainment into the privacy of home media, the neighborhood grew a little nicer, if not quite “gentrified,” by the late 1990s and early 2000s. There are pricey condos and good restaurants there now.

Sometime in the mid-1970s, a second plaque was placed on the ground closer to the actual location, but once again this seemed like an afterthought. A more proper monument was promised for decades, ground was finally broken in 2016, and in December 2018, Liberty Tree Plaza was unveiled on the former property of Deacon Elliott. It’s nothing too elaborate, just some planter boxes you can sit and rest on, a slanted, elevated slab with “Liberty Tree Plaza” carved into it, a little in-ground lighting, and some smaller variety of elm along the back edges of the planter boxes. (Because of underground utilities, trees can’t be too big or go too deep around here.) A circle of darker paving represents the area where the actual Liberty Tree once stood. Nothing to marvel at here, but it beats a neglected plaque across the street, or the now-gone plaque on the ground.

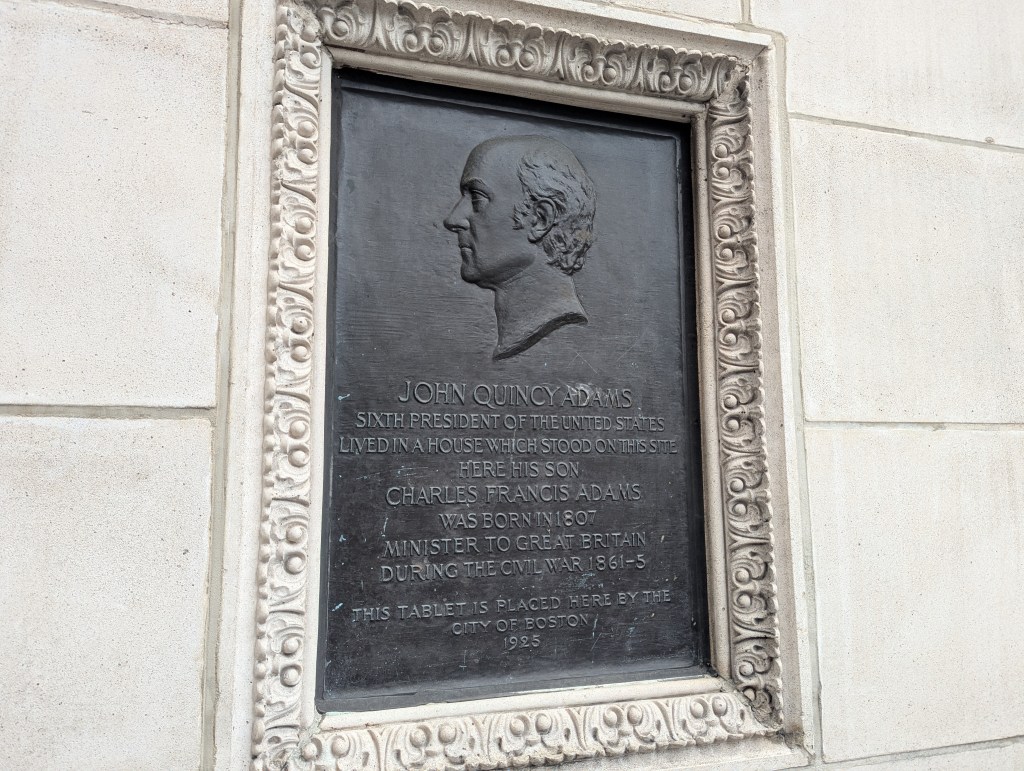

On the way back to Boston Common, another historical marker caught my eye. Evidently, in 1925 the City of Boston thought it worthwhile to slap a plaque where John Quincy Adams occupied a long-gone house on the corner of Boylston and Tremont Streets. One of his sons, Charles Francis Adams Sr., was born there in 1807. JQA’s tenancy must have been very brief or very intermittent. After a solid hour of looking, I could find no online*** evidence of this house at all…except on a website that catalogs historical markers. So there you go.

I thought I knew elms. I grew up in the smallish Northern California town of Woodland (population just over 30,000 when I was a kid), officially nicknamed the “City of Trees.” There are 16,000 city-owned trees, and thousands more on private property, many of them a century or more old. It’s why I could never live in a place that didn’t have shady, tree-lined streets. It’s in my blood. We had massive valley oaks, laurels, buckeyes, cottonwoods, willows, a few exotic Canary palms…and what I believed were elms. There was certainly an Elm Street, as there was in most small towns. As it turns out, what I thought for years were elms were actually London plane trees, planted in abundance on the east side of Woodland (my old stomping grounds) in the 1920s. Woodland once had its share of elms, but most were wiped out in the 1930s by the nefarious elm leaf beetle (not Dutch elm disease, which did its damage further east around the same time). A few hardy specimens remain, but I guess I wouldn’t know an elm if it fell on me.****

The next not-really-there tree to visit once stood on Boston Common.

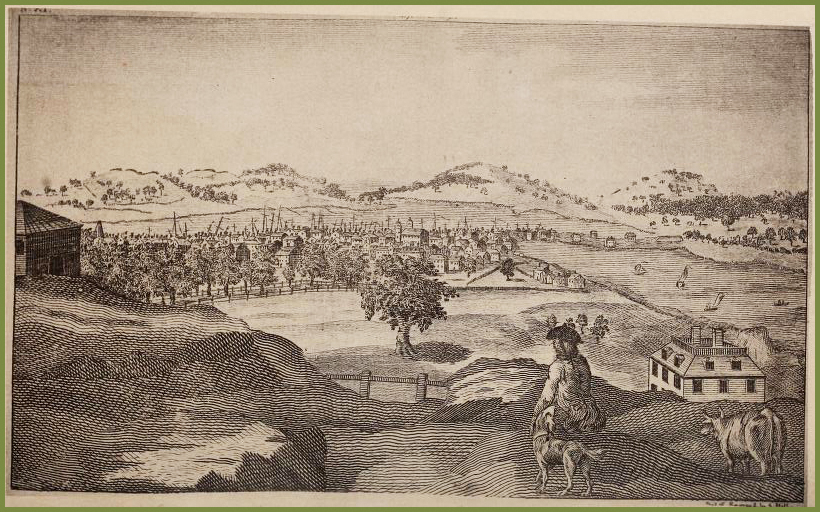

The land that makes up the Common was once owned by early European settler William Blaxton. In fact, for five years Blaxton was the sole occupant of the Shawmut Peninsula — the rocky outcrop surrounded at low tide by endless mudflats that is now the heart of modern Boston. In 1630, he invited the Puritan settlers across the river in the struggling Charlestown settlement to re-locate in order to have a better water supply (paying him for the land, of course). Blaxton kept fifty acres in the southwest portion of the peninsula for himself.

Like most non-Puritans, Blaxton found the uptight, pedantic, joyless Puritans deeply irritating to be around. And by 1634, there were about 4,000 of these pests right on his doorstep as the new city of Boston began to fill up with immigrants of the Great Puritan Migration. He arranged to sell most of his fifty acres to Massachusetts Bay Colony governor John Winthrop for £30, and hightailed it out of there the following year, ending up in what is now Rhode Island. Winthrop had raised the money to buy the land by levying a one-time, six-shilling tax on Boston homeowners. The land was then turned over to be used by the citizens as “common grazing land” for their rapidly increasing number of cattle. It was also the city dump. One other intended use was for recreation — a place for Bostonians to take in the garbage- and manure-scented air and for their children to play amongst the rubbish and cow pies, making Boston Common the oldest public park in America. (Dumping on the Common was wisely forbidden as early as 1652, but the cows stuck around awhile.)

A graveyard, the Central Burying Ground, was added in 1756, and became the last resting place for many British soldiers who died of disease in camp and on the slopes of Bunker Hill in 1775. And also for portrait artist Gilbert Stuart, who painted the first six U.S. presidents. His painting of Washington was what was used for the one-dollar bill. The last burial there took place in 1856.

During the Siege of Boston in 1775-76, the Common was the primary encampment area and training field for the British army. The march on Lexington and Concord began here, with 700 redcoats clambering into boats to cross the Charles River, which at high tide lapped right up against the Common’s western edge in those days. (The area has since been filled in and is now the Beacon Hill neighborhood.)

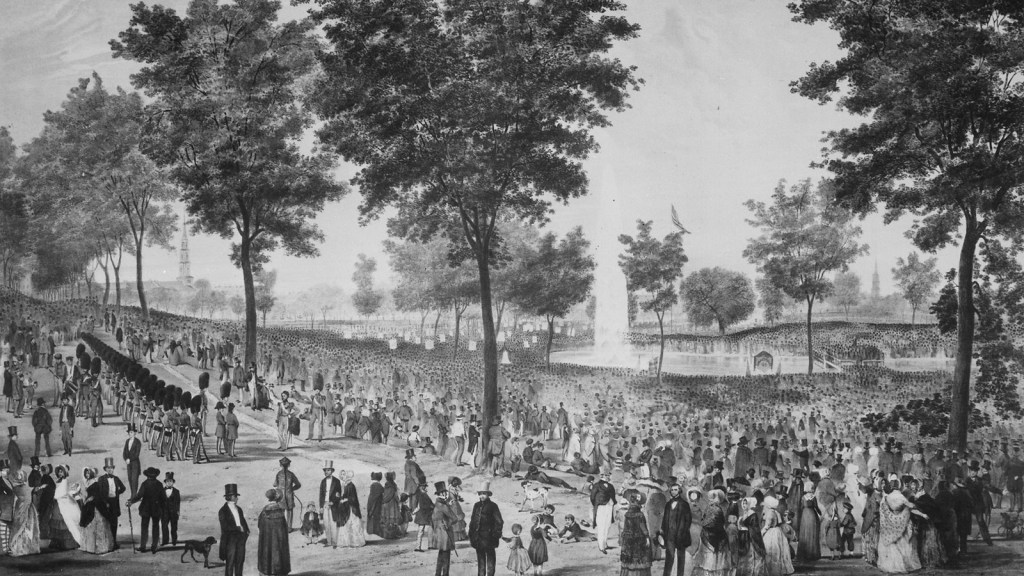

As Boston grew, it became increasingly impractical to have herds of cattle wandering the area. The cows were banished in 1830. This was right around the beginning of the urban parks movement. The Common’s hills were leveled, trees were planted, and walkways were laid out. Scrubby pastures became manicured lawns. A wrought-iron fence was put up around the perimeter in 1836. In the 1840s, a municipal water system came to the city, and the old, muddy Frog Pond was lined with concrete and featured a water plume that could blast ninety feet into the air. In 1867, a massive fountain imported from Paris was installed.

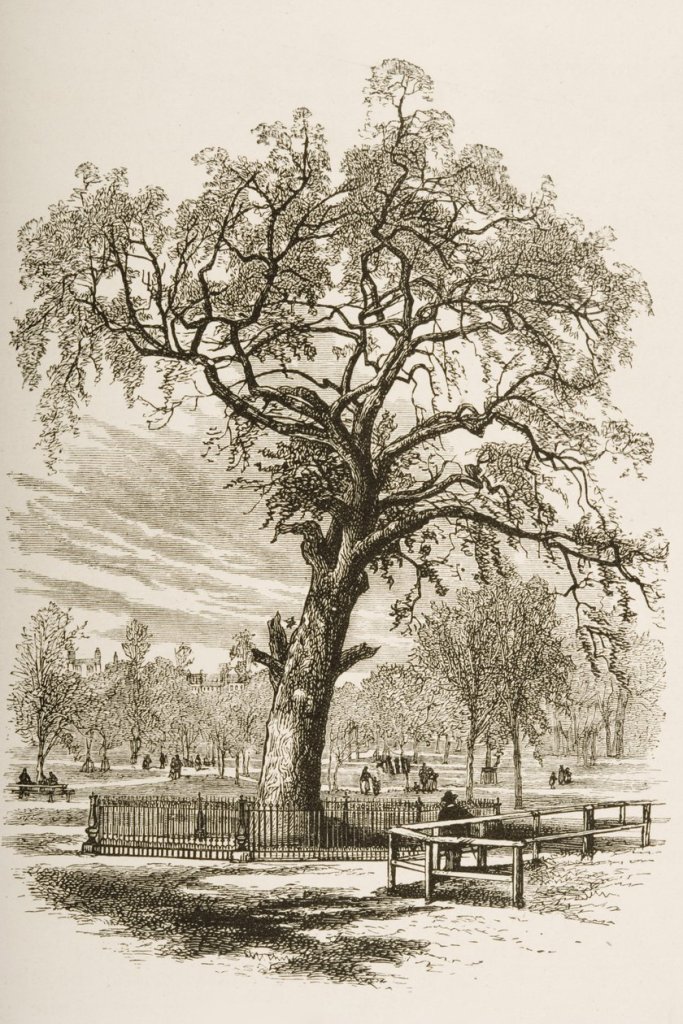

A silent witness to all this was the Great Elm.

The Great Elm was older than the Liberty Tree, and it’s said the Sons of Liberty met there as well. It was probably there when William Blaxton built the first dwelling on the peninsula in 1625. It became the centerpiece of Boston Common, eventually growing over seventy feet high, with a girth of twenty-two feet at its base. Several historical websites state it is the where the first Methodist sermons in New England were delivered in 1790, probably in acknowledgment that it was the Methodists who made the effort to install the plaque on the site. I tried researching the origins of Methodism and Wesleyan theology to maybe do a paragraph here, but it’s all the usual nitpicking sectarian gabble that makes my eyes glaze over whenever I try to fathom why anyone cares.

Before the Puritans’ dominance in the area began to wane in the late 1600s, the Common was the area for the public punishments they loved so much. The city pillory and whipping post were located right next to the Great Elm. And the thick branches were perfect for a good hanging. If there’s one thing a Puritan cannot abide, it’s someone who holds marginally different religious views. It is of course one of the great historical ironies that the poor, downtrodden Puritans left England because they were persecuted, only to come to Massachusetts to do quite a bit of persecution of their own. The Quakers, who believed in social justice, gender equality, and world peace were particularly despised as vile, demonic heretics, and Massachusetts passed a law in 1658 that all Quakers were banished from the colony “on pain of death.” In fact, the tiny handful of Quakers still arriving from England (did they not get the memo?) were literally yoinked off their ships and hauled before the Boston court to be officially banished before their feet were dry.

Most Quakers took the hint and got the hell out of there, but some stubbornly refused banishment. William Robinson and Marmaduke Stephenson were hung on a gallows on Boston Neck (the narrow isthmus that connected the Shawmut Peninsula to the mainland — colonial Boston was practically an island, see above map) for returning after banishment. Mary Dyer, already twice banished and returned, was supposed be executed that day as well, but was reprieved at the literal last minute as the rope was placed around her neck. She was banished a third time, and returned again, bound and determined, it seemed, to be a martyr for the Quaker faith.

She got her wish. She swung from a branch of the Great Elm on June 1, 1660.

When the tree’s lower branches grew too fragile to support hangings in 1769, no one wanted to give up their favorite execution spot, so a gallows was built adjacent to it.

How about the story of Rachel Wall? Although not as well known as Anne Bonny or Mary Read, Rachel Wall was one of the few people who could legitimately be called a female pirate. Born around 1760 into a respectable farming family in Pennsylvania (possibly with the surname Schmidt), she married a fisherman named George Wall. While he was away on his fishing trips, she took work as a domestic servant. On one voyage, George Wall fell in with bad companions and upon his return, they convinced Rachel to join them in a life of partying and debauchery. When the money ran out, they figured they could either return to their boring day jobs…or turn pirate. The choice was easy. (It is rumored that George Wall and his motley crew were former privateers from the Revolution days, so this came naturally to them.) They borrowed a schooner and prowled the Isles of Shoals off of New Hampshire, looking for targets. The best time to strike was just after a storm. When they spotted a likely victim, they struck their sails and feigned storm damage. The male crewmembers hid themselves away. Rachel remained visible, a comely lass looking helpless in a torn dress, waving a handkerchief and screaming for help. When the unknowing ship pulled alongside, George and his crew jumped out and attacked. (By the way, all of this backstory is based on her own written confession and a few other very unreliable sources, so salt, grain, etc.)

Between 1781 and 1782, the Wall gang allegedly took twelve ships and killed 24 sailors, scuttling the vessels and dumping the weighted bodies, leaving no trace. One estimate says they stole a total of $6000 (a hefty sum in the 1780s) and unrecorded amounts of miscellaneous booty***** before George and the crew were swept overboard in a hurricane. Rachel managed to cling to the ship. Some of the crew were known to have survived and were rescued. The fate of George Wall is unclear. The most common opinion is that he drowned, but Rachel seemed to believe he survived and abandoned her. (Adding to the confusion is Rachel’s account of trying to break him out of jail as late as 1785.) She ended up in Boston, returning to work as a household servant…with a twist. She still had the larceny bug, and at night would sneak aboard ships moored down at the docks, and steal whatever she could, using it to fund her “lewd and wicked” lifestyle. She was arrested on a couple of occasions, and even got fifteen lashes on her bare back. This did not prevent her from getting bolder as time went on, and her final arrest was when she brazenly snatched a bonnet right off another young woman’s head (one source says she went for the shoes and earrings too, which sounds like a hell of challenge). Oh, and she also attempted claw her victim’s tongue out. Rachel Wall was indeed a wild card, although she maintained she never directly killed anyone during her brief piracy career.

Stories circulated later that she was actually convicted of piracy. At least one source spun it as Wall demanding to be tried as a pirate and not a mere robber, as if she were proud of her swashbuckling legacy. That sounds a little over-romanticized to me. The existing court records and fragmentary newspaper covereage are pretty clear. She went down for a third conviction of robbery, which carried the death penalty at that time. She was a sad, remorseful, broken woman in the days leading up to her execution, nothing like Geena Davis in Cutthroat Island, despite stories by starry-eyed revisionists.

Governor John Hancock put his famous signature on her death warrant, and Rachel Wall met her fate at the Great Elm gallows on October 8, 1789. She was the last woman hanged in Massachusetts. After over a century-and-a-half sending heretics, accused witches, pirates, disobediant slaves, random Native Americans who wandered too close, and common criminals to meet their maker, the last public execution on the Common was in 1817.

Around the turn of the 19th century, the Great Elm was feeling its age. Every storm claimed a few more branches. A crack developed down the center, gradually widening into a huge cavity. By 1854, for public safety and to protect the tree itself, an iron fence was placed around it. Everyone knew its days were numbered when it began to list noticeably after an 1860 storm.

The Great Elm finally succumbed to the elements. A massive storm blew it down on February 15, 1876. As the venerable tree lay on its side, its gargantuan root network exposed, the citizens of Boston swarmed over it, claiming parts of it as souvenirs. All over Boston, there are people who unknowingly own heirloom picture frames, serving trays, and other wooden tchotchkes made from the Great Elm. There’s even a Great Elm chair in the Boston Library.

The American elm is the official state tree of Massachusetts, and they used to be incredibly common across the North American continent, until Dutch elm disease claimed the majority of them in the 1930s. A similar fate befell another iconic American tree, the chestnut, which were decimated by a fungus called “chestnut blight” in the early 1900s. Newer hybrid species of both are out there, but it’s not quite the same.

Of course there was a plaque marking the Great Elm’s former location thanks to the Methodists. Not being a Boston native, it was a little difficult for me to find. I went to where my map app told me where it would be. No dice. I wandered around randomly for a few minutes, my shoes getting wetter and wetter with accumulated dew. My wife took a seat on a nearby bench as I scratched my head and looked around, hoping to catch a glimpse of a flat plaque flush with the ground. Every time I spotted a likely prospect, it turned out to be a drainage grate or an irrigation control box lid. Finally I began walking in ever-widening circles from the GPS-approved icon on my phone.

I finally found it. A heads-up to any intrepid urban explorer following in my footsteps, Google Maps has it pinned about thirty feet from its physical location.

In the next entry, we hit the Freedom Trail…

*For the record, the Loyal Nine were officially anonymous, but widely known to be John Avery, Henry Bass, Thomas Chase, Steven Cleverly, Thomas Crafts (a Japanner artist), Benjamin Edes (editor of the Boston Gazette), Joseph Field (the ship captain), John Smith, and George Trott. Unless otherwise noted, these guys were all jewellers, braziers, or distillers.

**Not to be confused with the early 1800s American political party of the same name. In the 1700s, a “whig” was a member of the anti-royalist faction in Parliament, or a general term for anyone on either side of the Atlantic who thought the king wielded too much power.

***one print source, Fred Kaplan’s John Quincy Adams: American Visionary, makes a vague reference to Adams owning several rental properties around the city. In 1807, he was spending most of his time in D.C. serving as U.S. senator, so it seems he holed his family up in one of these houses for the birth of his second son. Why here and not the Adams family (*snap*snap*) compound in Quincy is not explained.

****Sorry for the digression into tree varieties in my childhood town, but I’ve been reading a lot of Pynchon lately.

****** “Miscellaneous Booty” would be a great band name.

SOURCES:

Boston 1775 (several entries on the Loyal Nine and Liberty Tree)

Revolutionary Spaces: Legacy of the Liberty Tree

Journal of the American Revolution: Visiting Boston’s Liberty Tree

Boston Tea Party Ships and Museum: The Loyal Nine

Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation Musuems: What was the Stamp Act?

State Library of Massachusetts: The Great Elm on Boston Common

The Next Phase Blog: The Great Elm on the Boston Common

Boston Hidden Gems — Boston History: The Great Elm

Landscape Architect’s Guide to Boston Common

The Beehive (Massachusetts Historical Society Blog): The Tree on Boston Common

Pirates and Privateers: The History of Maritime Piracy

National Park Serivce, People: Rachel Wall – Pirate

EBSCO Research Starters: Rachel Wall

City of Woodland: Landmark Trees

Good Ol’ Wikipedia, the Lazy Researcher’s Friend

Bunker Hill: A City, A Siege, A Revolution by Nathaniel Philbrick (2013)

I am sure there a a few more that I perused, but those are the main ones.

Pingback: The Holy Bee’s Adventures in Massachusetts, Part 2: The Freedom Trail Begins | Holy Bee of Ephesus

I tend to quietly snicker at suggestions from various people in our lives that you should write a book…but…you really could have, in a different life, if you were more highborn…