“To my mind I’ve already proved I can act. The trouble was that I used to approach acting like a rock ‘n’ roller. I was getting parts simply because of who I was. Geezers would say what a great idea it was to have a Beatle in their movie. And the fact that I wanted to act, that I felt I could act, wasn’t really the issue. But no one is going to offer Ringo Starr a top role these days just because I used to be one of the Beatles. I’ve got to be able to do the job…Maybe Caveman is the dawn of a new era for me.”

— Ringo Starr, 1980

Caveman — the movie that Ringo hoped would finally launch his career as a…well, maybe not “Serious Actor,” but at least someone capable of playing a leading role — would be the feature directing debut of Carl Gottlieb. It was intended to be an homage to B-grade humans-coexisting-with-dinosaurs schlock like One Million Years B.C. and When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth, and to the silent slapstick of Chaplin and Keaton (who had both done comic “caveman” routines). The concept was not without promise, and Gottlieb had an impressive resume. Ringo had good reason to be hopeful.

Carl Gottlieb got his start in the 1964 iteration of the San Francisco improv troupe The Committee, along with guys like Howard Hesseman and Peter Bonerz. They transferred to L.A. later in the 60s, and Gottlieb moved on to TV writing before the decade was out. He scored an Emmy for writing for the controversial Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour in 1969. In addition to penning scripts for The Bob Newhart Show, All in the Family, and The Odd Couple as the ‘70s commenced, he also maintained a minor presence in the acting world, most notably in the small but dryly funny role as anesthesiologist Capt. “Ugly John” Black in Robert Altman’s 1970 feature film version of MASH.

Lightning really struck for Gottlieb in 1974 when his friend Steven Spielberg (it helps to know the right people) hired him to do a quick polish on Peter Benchley’s screenplay for Jaws. Benchley, adapting his own novel, had created a screenplay that was serviceable but not great. The characters lacked dimension and the tone was humorless and relentlessly dark. What was intended to be a one-week job blossomed into Gottlieb traveling to the Martha’s Vineyard location for the duration of the production and doing an entire re-write in close collaboration with Spielberg while shooting was underway. (He also appeared in the film as Meadows the newspaper editor.) Gottlieb’s version was a huge improvement, with likeable characters and a subtle touch of humor. Jaws went on to be the first true summer blockbuster in 1975.

Another feather in Gottlieb’s Jaws cap was his publication that same year of The Jaws Log, a book chronicling the film’s difficult production from a first-hand perspective. It became a behind-the-scenes classic in its own right among film buffs (a copy has graced the Holy Bee’s shelf since childhood), and has been updated and re-published multiple times.

Everyone’s heard the Hollywood cliche quote — “…but what I really want to do is direct.” Gottlieb was no exception, and got his chance when Steve Martin tapped him to direct his short film The Absent-Minded Waiter in 1977, which was nominated for an Academy Award. This led to him co-writing Martin’s first starring feature The Jerk (1979).

Around 1977 or ‘78, a movie producer named Lawrence Turman (The Graduate) was inspired by seeing comedian Buddy Hackett play a caveman in a Tonight Show sketch. “As a kid, I loved the film One Million B.C. [the 1940 version with Victor Mature], and the thought of doing a picture like that, using the same wardrobe and the same language, but played for laughs, seemed like a great idea.”

Turman and his producing partner David Foster hired Gottlieb and Rudy De Luca (fellow TV writer and frequent Mel Brooks collaborator) to do a screenplay based on this idea. Trusting Gottlieb’s comedy instincts, the producers decided to have him direct as well. Although they felt Gottlieb was on solid ground humor-wise, they hedged their bets when it came to the rookie director’s handling of visual effects. They brought in stop-motion guru Jim Danforth, who had done the effects on Caveman’s inspiration One Million Years B.C. and similar films, to direct all the sequences with the dinosaurs. He would be credited as a co-director with Gottlieb.

“When we wrote the movie, it required a clever but small person, not someone with an imposing stature,” said Gottlieb. “We wrote it without an actor in mind, and then, when the screenplay was finished, we were looking at Dudley Moore or Ringo…Those were the choices. Dudley was unavailable and we went with Ringo because we met with him and found out he was interested in doing it…I told him this was not like anything he’s done before. It didn’t depend on his being a Beatle or a famous person — it’s actually an odd, funny little acting part.”

Filming began in February 1980 in Sierra de Organos National Park outside of Durango, Mexico. Joining Ringo in the cast were Dennis Quaid, Shelley Long (two years before Cheers), football legend John Matuszak, former Bond girl Barbara Bach (The Spy Who Loved Me), and veteran comic actors Avery Schreiber and Jack Gilford (if you don’t know their names, you know their faces).

Armed federales surrounded the location each day to protect the production from pillaging by the local bandits — and to make sure the visiting Americans had no narcotics, meaning the cocaine-loving Ringo had to do without, so he doubled down on his alcohol intake. He brought along his friend Keith Allison to be his “minder,” making sure he made it on set each morning in relatively decent shape after long nights in Mexican cantinas.

About two-thirds of the way through production, word came through from the Director’s Guild that Jim Danforth would not be allowed a co-director’s credit for directing the dinosaur sequences. He walked off the project. Gottlieb would receive sole credit as director. Danforth declined any onscreen credit, so visual effects are credited to his partner David Allen (who would later go on to do some great stuff for George Lucas’s effects company Industrial Light & Magic).

The bulk of the location work was done at Sierra de Organos, followed by a week in Puerto Vallarta, and concluding with soundstage work at Churubusco Studios in Mexico City. As production proceeded, Ringo and castmate Barbara Bach found themselves in a developing relationship. After rehearsing a comedic “seduction” sequence with each other the night before the scene was shot, Ringo lingered in Bach’s hotel room after everyone else had left, and the couple showed up the next morning hand-in-hand. Bach was unawed by Ringo’s storied past. “I was never that much of a Beatles fan, which made it easier,” Bach said. “I just treated him like everyone else.”

Despite the credit dust-up with Danforth and a few queasy mornings with hungover cast members, shooting went smoothly and was all over within six weeks. Everyone had gotten along famously and went home satisfied with the results.

CAVEMAN

Released: April 17, 1981

Director: Carl Gottlieb

Producers: Lawrence Turman, David Foster

Screenwriters: Carl Gottlieb, Rudy De Luca

Studio: United Artists

Cast: Ringo Starr, Barbara Bach, Dennis Quaid, Shelley Long, John Matuszak, Avery Schrieber, Jack Gilford, Evan Kim, Ed Greenberg, Cork Hubbert, Mark King, Carl Lumbly

Caveman tells the story of Atouk (Ringo), a meek and put-upon prehistoric cave dweller in the year “one zillion B.C.” The leader of his tribe is Tonda (John Matuszak), a bullying alpha male who forces his food-gathering expedition to abandon slow-witted Lar (Dennis Quaid) when he is injured in a dinosaur attack triggered by Atouk. Tonda also has a beautiful mate Lana (Barbara Bach), with whom Atouk is secretly in love. Atouk is already on the outs with the tribe for bungling the expedition, and finds himself cast out entirely when he is caught attempting to “seduce” Lana (after drugging her with sleep-inducing berries, which is pretty creepy).

Out in the wilderness, Atouk is reunited with Lar, and the two begin gathering other outcasts together into a “misfit” tribe, beginning with Tala (Shelley Long) and her blind father Gog (Jack Gilford), and eventually including a dwarf, a gay couple, and Nook (Evan Kim), who happens to speak perfect modern English. (The rest of the misfits find him totally incomprehensible.) The misfit tribe’s discoveries include standing erect, music, fire, and cooking. They also create weapons and armor, allowing them to strike up a rivalry with Atouk’s original tribe. There are multiple encounters with Danforth-designed dinosaurs, and a run-in with the Abominable Snowman before the whole thing ends up with Tonda vanquished and Atouk being acknowledged as leader of the combined tribes. Atouk ends up choosing Tala over the shallow Lana, and “they lived happily ever after” as the onscreen words tell us.

Whether or not it was Gottlieb’s intent, what he ended up with is essentially a stoner comedy. The broad, basic humor is the textbook definition of “sophomoric” and perhaps very appealing to someone watching this glazed-over high at two in the morning. The film is reaching for a kind of sweet silliness, but too often comes off as just really, really dumb. It’s almost as though Gottlieb and De Luca secretly passed off their screenwriting duties to a group of fifth-grade boys. Falling into something (water or ideally something grosser), or simply falling over, is considered the pinnacle of comedy. Cartoon sound effects are employed to an extreme degree. Fart jokes and poop jokes abound.

The one element that seems to work well is that the dialogue consists of about fifteen nonsense words in “cavespeak,” so most of the acting is done through grunts, pantomime, and facial expressions…and the performers are clearly having a great time working that way. Dialogue was always Ringo’s Achilles’ heel, and now he could eschew his flat Liverpool monotone and rely on his natural physicality and expressive eyes. Shelley Long also came off very well and is kind of adorable, not yet associated with her uptight Diane Chambers character. In fact, the only one who seems a little stiff and hesitant is Barbara Bach. The animated dinosaurs are actually pretty charming, and for the most part steal the show.

When all is said and done, Caveman is a harmless little film that feels interminably long at barely 90 minutes. Despite Lawrence Turman’s moment of inspiration, perhaps “comedic cavemen” is a concept best left to Buddy Hackett sketches and Charlie Chaplin shorts.

The reviews were surprisingly kind. The New York Times called it “nicely whimsical,” and the Village Voice went so far as to use the term “enchanting.” Newsday went with “infantile, but also playful and appealingly good-natured.” The Washington Post was a little more realistic: “Priceless it ain’t, but if the kids are determined to enjoy it, the brain damage should be minimal.” Ringo was also singled out for praise, with many comparing his performance favorably with his Beatles films. It generated a mediocre $16 million at the box office, but the budget was only $6.5 million.

So what happened? No one seems to know. Despite the good reviews for his performance, and despite the fact that, all things considered, Caveman was far from a disaster, Ringo was never offered another major film role again.

Carl Gottlieb went on to direct two sequences in the 1987 cult anthology film Amazon Women on the Moon. Each of his sequences perfectly encapsulates the two Gottlieb directing styles — “Pethouse Video” was obvious and crass, and “Son of the Invisible Man” was subtle and clever. (He wrote neither.) He hasn’t directed since, nor has he written anything of note since the ‘80s.

Ten days after Caveman’s release, Ringo and Barbara Bach were married at Marylebone Town Hall in London. Now happily (if blearily) hitched, he was still barely keeping his head above water career-wise. No movie producers were calling him. His most recent solo album, Stop and Smell the Roses (October 1981) sold about six copies and is now widely regarded as one of the worst of all Beatle solo albums. He was dropped by yet another record label. His heavy drinking continued unabated, and his new spouse joined in. “Every couple of months she’d try and straighten us out,” Ringo said. “But then we’d fall right back in the trap.”

His next — and to date, final — movie role was handed to him by an old friend: Paul McCartney. He was to play a drummer in Paul’s band. Not too much of a stretch.

When I sat down in the theater for a screening of The Muppets Take Manhattan in the summer of 1984 as a 9-year-old Beatles superfan, imagine my delight in seeing the trailer for Give My Regards to Broad Street, starring the one and only Paul McCartney. It never came close to playing at the lone three-screen theater in my small hometown, which may have been a good thing. I was pretty bored sitting through it a few days ago as a 49-year-old, imagine how a 9-year-old Holy Bee would have taken it. Later that same year, I even wandered out of the auditorium during Breakin’ 2: Electric Boogaloo to play Galaga in the theater lobby because it wasn’t fast-paced enough for me.

Let’s rewind a bit…

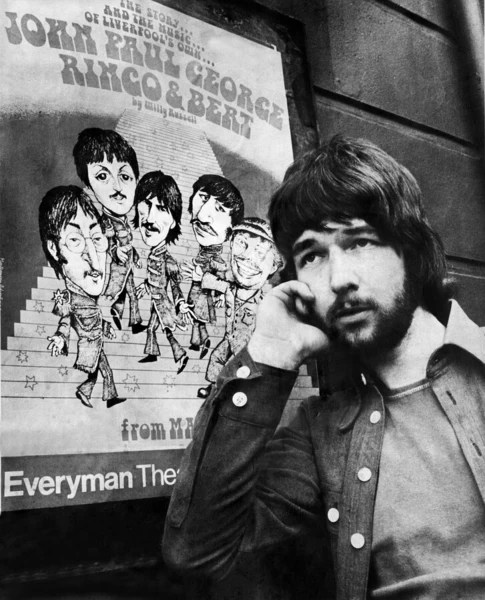

Paul had been toying with the idea of making a film for years. After considering the science fiction genre (he went so far as to have meetings with both Isaac Asimov and Gene Roddenberry), he decided to base a more down-to-earth movie around his acclaimed 1973 album Band on the Run. He commissioned a script from Willy Russell, the Liverpool writer behind the 1974 musical play John, Paul, George, Ringo…and Bert. Although none of the Beatles were overly fond of this “alternate history” version of their story, Paul felt Russell had the necessary skills to pull off a cinematic story featuring Paul and the current (third) version of Wings, then in the midst of recording their 1979 album Back to the Egg. Russell and collaborator Mike Ockrent went to Jamaica on Paul’s dime and crafted a Band on the Run script.

After a read-through, Paul declared himself satisfied and proudly said he’d already cleared two months’ time in his schedule after the Egg sessions to produce and act in the film. After picking his jaw up off the floor, Russell explained that two months was nowhere near enough time to put a movie through pre-production and filming. There was no crew, no cast besides Paul and the band, no budget, no studio…and the cinematically naive Paul expected to start in a few weeks’ time! “Look, you can’t do this like Magical Mystery Tour,” Russell recalled warning Paul. Obviously, Paul’s two month production window came and went with nothing to show for it. Paul later assured Russell that the film would be made as soon as Wings returned from their 1980 tour. That was the last time Russell heard from him.

Events intervened. Paul was arrested and briefly jailed in Japan for attempting to bring marijuana through customs. John Lennon was murdered. Wings imploded. Paul focused his intense work ethic on recording a lavish new solo album, Tug of War (April 1982), which would top the charts on both sides of the Atlantic and fill the airwaves with his Stevie Wonder duet “Ebony and Ivory.” When the McCartney Film Idea re-surfaced after all that, it was no longer Band on the Run. Paul had decided to write a new script himself, scrawling it on notepads in the back of his car as he commuted in his chauffeured Mercedes from his Sussex country home to handle business in London.

It was evident that Paul was no screenwriter. What he ended up with was a paltry 22 pages — essentially an extended story treatment. Paul figured the running time could be padded by adding several musical sequences. It would be called Give My Regards to Broad Street, the title based on the old George M. Cohan song “Give My Regards to Broadway” and the fact that Paul’s story about someone stealing the master tapes of his new album concluded at London’s Broad Street train station. It was at this point that Paul should have sought out a professional writer (Willy Russell was probably available) to turn his outline into a real screenplay. He decided to forge ahead with what he had. The film never did have an official finished shooting script.

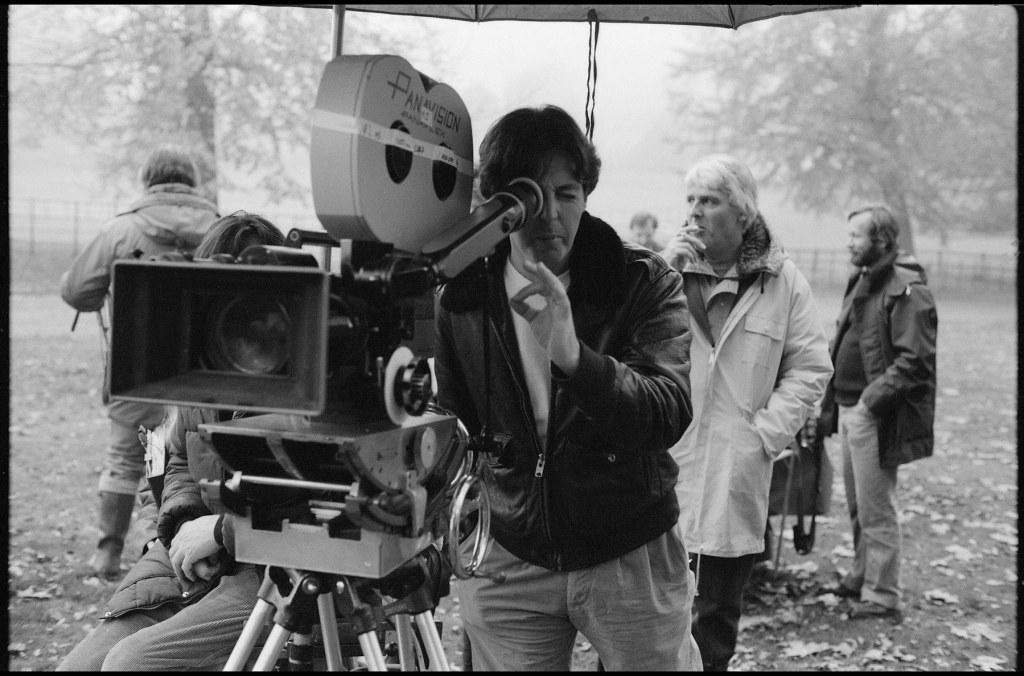

Paul went to friend and film producer David Puttnam (we’ve already talked about him in previous entries) for guidance. Puttnam looked over the flimsy “script” and very wisely suggested doing it as a one-hour TV movie. Paul reluctantly accepted this advice — for now. Next came the question of director. Puttnam suggested commercial director Peter Webb, who could do imaginative visuals on a TV budget. Webb agreed to do it. He would be making his first non-advertising film. His newcomer status and agreeable personality meant he would be open to supervision and endless creative input from Paul, who would unofficially co-direct.

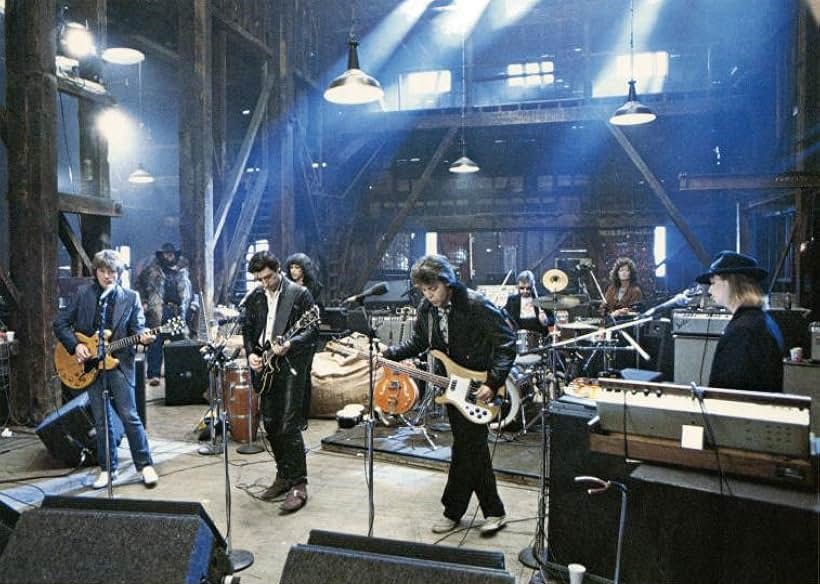

Rather than being done ahead of time as was the norm, the songs heard in the film were recorded simultaneously with the filming, and some of the music would be done live on set. Wings was no more, so Paul assembled a new group of musicians to record the necessary songs and appear in the film. The bulk of the soundtrack was recorded by the core band of Paul (vocals, bass guitar, acoustic guitar, piano), his wife Linda (the lone remaining Wings member on keyboards and backing vocals), and Ringo (drums). Electric guitars were provided variously by Chris Spedding, Dave Edmunds, Steve Luthaker, and a few others. Paul wrote three new songs for the film: “Not Such a Bad Boy,” “No Values,” and the brilliant “No More Lonely Nights” (featuring Pink Floyd’s David Gilmour on lead guitar). He also re-recorded several of his earlier songs, including six from the Beatles: “Yesterday,” “Good Day Sunshine,” “Eleanor Rigby,” “Here, There, and Everywhere,” “For No One,” and “The Long and Winding Road.”

Like the soundtrack recording, the casting of the non-musician characters was done on the fly as the filming was already underway. Australian actor Bryan Brown (F/X, Cocktail) was recruited to play Paul’s manager, Steve (based directly on Paul’s Australian manager at the time, Stephen Shrimpton). Barbara Bach was given a small role as a journalist. Rising star Tracey Ullman was cast as the suspected tape thief’s New Wave girlfriend.

The hastily-arranged project began filming, funded by Paul’s own money, in November 1982, still with intent of it being made-for-TV. But Paul continued to have nagging big-screen ambitions, and was quietly making inquiries about expanding the film’s scope even after shooting had begun. His goal was achieved when his father-in-law and legal advisor Lee Eastman was able to get 20th Century Fox on board by the end of December. Without seeing the (non-existent) script and based on Paul McCartney’s name and some of the early footage, Fox agreed to provide the full feature film treatment. The studio ponied up a budget of $6.8 million (roughly the same as Caveman) and assigned a producer to monitor the spending. (Although not credited as such, Give My Regards to Broad Street’s only real producer was Paul McCartney.)

Bouncing back and forth between recording the music and filming the newly-expanded movie, production stretched into July 1983. The budget blew up to $9 million, despite oversight from Fox. (Who was willing to tell Paul McCartney “no”?) Around now, Paul decided he wanted a “heavy hitter” actor in the cast, so renowned thespian Sir Ralph Richardson was convinced to do a short scene, even though his health was precarious. (Richardson was a giant of British theater, a contemporary of and considered equal to Laurence Olivier and John Gielgud, but was less known to American audiences because his film roles were mostly smaller British productions.)

Post-production and putting the final touches on the soundtrack album dragged on for months, and Give My Regards to Broad Street was not slotted into Fox’s release schedule until the following autumn. The studio was certain it had a hit on its hands and that old-fashioned movie musicals were going to make a comeback, so they splurged on a massive promotional campaign…

…then the studio executives watched a rough cut, and the mood turned to panic. One of them described what they saw as “Paul McCartney’s $9 million home movie.” It was nothing more than a vapid vanity project, not the fun Hard Day’s Night-style romp they thought they had paid for.

GIVE MY REGARDS TO BROAD STREET

Released: October 23, 1984

Director: Peter Webb

Producer: Andros Epaminodas

Screenwriter: Paul McCartney

Studio: 20th Century Fox

Cast: Paul McCartney, Bryan Brown, Philip Jackson, Ian Hastings, John Bennett, Tracey Ullman, Ralph Richardson, Barbara Bach, Ringo Starr, Linda McCartney, Giant Haystacks

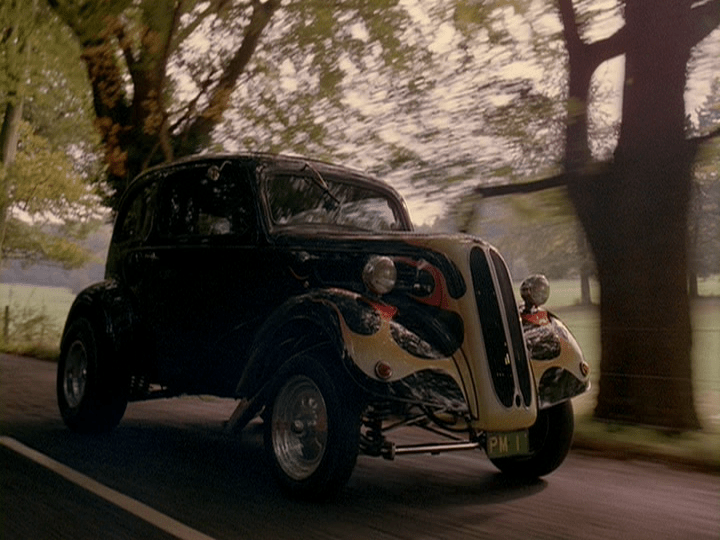

The film begins the same way the idea for the film had begun: a bored, millionaire rock star (Paul) stuck in traffic in his chauffeured limo, scrawling away in a notebook. He begins to daydream. Suddenly, he is driving himself though the countryside in a hot rod (a British hot rod — a 1955 Ford Popular — so don’t get too excited) and wearing a snazzy Hawaiian shirt. He receives a call on his car phone (imagine!) from his manager Steve (Bryan Brown) telling him that the master tapes for his newly recorded album have disappeared. They had been entrusted to studio employee Harry (Ian Hastings) for delivery to the factory, but neither Harry nor the tapes have shown up. Everyone knows Harry has a criminal past, and fears he will sell off the tapes. Due to some convoluted reasons I failed to grasp, the disappearance of the tapes will somehow allow an evil conglomerate headed by the evil Mr. Rath (John Bennett) to force a hostile takeover of Paul’s record company.

What follows in a stylized “day in the life” of Paul McCartney. The missing tapes and potential takeover of his record company are dealt with mostly by Steve and various aides and executives as Paul goes through his normal schedule. He is determined to keep a cool head (and maintain his faith in Harry) as everyone around him is panicking. First is a recording session with his loyal drummer (Ringo), where they tape a medley of “Yesterday,” “Here, There, and Everywhere” and the Tug of War track “Wanderlust,” all with a surprisingly effective brass backing. (Beatles producer George Martin and ‘66-’69-era Beatles recording engineer Geoff Emerick appear as themselves in this sequence.)

This is followed by an elaborate full-dress rehearsal of another Tug of War song, “Ballroom Dancing,” for an upcoming TV appearance. (The rehearsal ends in slapstick chaos, with choreographed dancers spinning out of control, knocking over scenery, etc.).

In the TV studio commissary, a journalist (Barbara Bach) interviews Ringo while Paul comforts Harry’s girlfriend Sandra (Tracey Ullman), who is distraught over his disappearance. Up next is a video shoot for the 1976 Wings classic “Silly Love Songs,” featuring Paul and the band in elaborate space-age costumes and heavy face make-up (Ringo opted out of this one and is replaced by Toto’s Jeff Pocaro).

Trailed by the journalist who has formed an attachment to Ringo, Paul’s band then meets up at a rehearsal space and bashes out “Not Such a Bad Boy,” “So Bad” (from 1983’s Pipes of Peace, not yet released at the time of filming), and “No Values.” Shady loan shark Big Bob (pro wrestler Giant Haystacks) swings by the rehearsal to reassure Paul (who for some reason seems to be a close pal) that Harry doesn’t owe him any money, and in fact he hasn’t even seen him.

As night falls, Paul dashes off to the BBC for a radio interview and performances of “For No One” and “Eleanor Rigby.” The latter song segues into a lengthy fantasy sequence, featuring Paul in dress attire performing at the Royal Albert Hall, then morphing into a Victorian gentleman with muttonchop sideburns, picnicking along the Thames with the similarly-attired Linda, Ringo, and Barbara Bach.

After various flights of surrealism set to the lush McCartney instrumental “Eleanor’s Dream,” the whole sequence concludes with a top-hatted Paul stalking Harry along the rainy cobblestone streets of 1800s London. When we return to reality after twelve (very) long minutes, Paul decides to pay a visit to another friend, pub owner Jim (Ralph Richardson), who offers a little fatherly advice. (Some think that Jim is supposed to literally be Paul’s father — whose name really was Jim — but, apart from the character Jim casually calling Paul “son,” the relationship is left vague.)

By now it is closing in on the takeover deadline of midnight. Following a hunch, Paul goes to the Broad Street train station, and discovers that Harry has accidentally locked himself in a maintenance shed and been stuck there for the past 24 hours. The tapes are recovered. The record company is saved.

Then Paul wakes up in the back of his limo. It had all been a dream. “No More Lonely Nights” plays over the closing credits.

The film was released to absolutely devastating reviews. The notoriously nasty British press had their knives sharpened for McCartney and did not hold back. The Daily Star said “The pathetic plot…has all the suspense and interest of a wet tissue.” From the Daily Mirror: “Give My Regards to Broad Street is coy, whimsical, self-indulgent. But don’t call it a disaster — it’s far too dull for that.” The New Musical Express critic weighed in with “I find [the movie] wanting, severely debilitated. It could be the harbinger of his real decline.” And so on, across dozens of papers. The British media seemed to take the movie as some kind of personal affront, then took sado-masochistic glee in both wallowing in their own pain from being forced to watch it and being pointlessly cruel to McCartney himself. The American reviews weren’t much better.

Peter Webb was hospitalized for nervous exhaustion after turning in his cut of the film to the studio. He returned to the safe world of wine cooler commercials and never directed another movie. Sir Ralph Richardson died a few months after his scene was shot, and a favorite topic of the critics was how his immense talent was wasted in his final role.

Despite the vitriolic reviews that bordered on bloodlust, the film isn’t all that horrible. Oh, it’s not good, but when seen as simply a long-form music video, Give My Regards to Broad Street is passable viewing for a McCartney fan. Almost half of its running time is musical performances. The character of “Paul McCartney” was a level-headed, super-cool master musician, and as such was kind of an ego trip for the real Paul McCartney, and a little cringey for the audience. His performance as himself was a bit wooden, a bit awkward…but no worse (and actually better) than Ringo in something like Son of Dracula, and Ringo was the one supposedly pursuing an acting career. Peter Webb captured 1980s London in a fairly captivating, gritty style, and real actors like Brown and Ullman were very good given the non-script’s limitations. The costumes by four-time Oscar winner Milea Canonero (Chariots of Fire, Grand Budapest Hotel) were also noteworthy. (I’m sure Paul’s Hawaiian shirt was selected with care.)

Yes, it was a vanity picture. Yes, it was tedious and uninvolving. But offered the choice of this or truly pointless drivel like 200 Motels if I had to watch a solo Beatle movie again? Give my regards to Macca.

And I guess in a small way, Paul had the last laugh. The soundtrack album went to #1 in Britain, and the epic power ballad “No More Lonely Nights” (#2 in the UK, #6 in America) is now considered a classic McCartney song.

We’ve dealt extensively with Ringo. John (see Part One) and Paul were both one-and-done with solo acting roles. What about George?

Unlike Ringo or Paul, George had no ambition to be a film actor. However, he did end up being sort of a player in the world of British cinema in the 1980s — as a producer.

George had always been friends with the members of Monty Python, particularly Eric Idle and Michael Palin. When EMI suddenly pulled their financing from Python’s religion-themed Life of Brian film at the last minute due to concerns over its controversial content, George stepped in. He mortgaged his house and gave them the money. Just because 1) they were his friends and he wanted to help, and 2) he was a Python fan and wanted to see the damn movie. (Idle famously called it “the most expensive cinema ticket in history.”) In order to make it happen, he had to form a production company.

He and his business manager Denis O’Brien (not to be confused with the Irish billionaire) jointly founded HandMade Films. Python animator Terry Gilliam designed them a logo, and they were off and running. Monty Python’s Life of Brian came out in 1979 to universal accolades.

Over the course of the next decade, George and O’Brien had many successes. They produced the classic British gangster film The Long Good Friday, the Terry Gilliam fantasy Time Bandits which featured George’s underrated song “Dream Away” over the closing credits, Neil Jordan’s neo-noir crime drama Mona Lisa, and the excellent dark comedy Withnail and I. HandMade was considered a major boost to the moribund British film industry in the 1980s.

But there were two problems.

The first was that for every high-quality, high-grossing film HandMade produced, there were two bombs that bled money, most notoriously 1986’s Shanghai Surprise. Starring the newly-married couple Sean Penn and Madonna, the pair’s diva behavior on set caused the shoot to drag on endlessly, not helped by the constant presence of paparazzi and tabloid reporters. The film was finally released to almost no audience interest and some of the worst reviews of the decade. It lost millions. Other HandMade turkeys included the disjointed political satire Water with Michael Caine, and a limp comedy about hypochondria, Checking Out, with Jeff Daniels.

The second problem was Denis O’Brien. If ever there was a creature of pure commerce and without an artistic bone in its body, it was O’Brien. George at first admired him for sorting through and solving multiple issues with the former Beatle’s messy finances in the mid-1970s. But O’Brien’s financial acumen came at a cost. He had no imagination, no appreciation of cinema, and no taste. After the success of Life of Brian, the Python team hired him as their business manager, then were taken aback when they were exposed to his money-grubbing pushiness. Sure, the Pythons wanted to make money, but not at the expense of missing out on things they actually wanted to do and were creatively fulfilling for them. O’Brien couldn’t wrap his head around that concept. In Palin’s words, O’Brien tried to turn the comedy troupe into the “Python International Corporation,” with money funnelled into various offshore accounts and holding companies, often skirting the edges of legality. The Pythons were also put off by his obsession with Hollywood celebrity and its all its empty glitz. After butting heads for almost three years, they fired him.

Here’s an illuminating anecdote. When Terry Gilliam was making Time Bandits, he was having difficulty casting the role of the main villain. Simply named “Evil,” he was a more non-specific or universal form of Satan or the Devil. Gilliam eventually settled on the hulking David Warner, a well-established Shakespearean actor with a long, craggy face, piercing blue eyes, and a booming voice that could be by turns purringly erudite and genuinely frightening.

The actor O’Brien repeatedly pushed for?

Burt Reynolds. Just because he was super-famous at the time, and O’Brien felt that was the only qualification needed. A big name to put on the poster and in the commercials, regardless of literally anything else.

That tells you everything you need to know about Denis O’Brien.

Oh, and he also ripped off George and HandMade Films for millions. The company went defunct in 1991 due to his siphoning funds into his own pocket on George’s credit. George filed multiple civil lawsuits to get at least a small portion of his money back, none of which succeeded. As co-owner of the company, nothing O’Brien did was technically criminal, just duplicitous and reprehensible. (The upside, I suppose, was the fact that George was pretty much flat broke forced him – reluctantly – into participating in the Beatles’ Anthology project in 1995.)

Although he never wanted to really be an actor, George had no objection to occasionally popping in front of the cameras, and appeared in small cameos in three HandMade productions. All of which are too brief to merit a full write-up.

He was “Mr. Papdopoulos” in Monty Python’s Life of Brian (1979), a landowner who was going to lend the People’s Front of Judea a “mount” the following Sunday, presumably for Brian to give a sermon on. His one line — “hello” — was dubbed by Michael Palin doing his best George impression.

He was a nightclub musician in Shanghai Surprise (1986).

And he was a janitor in Checking Out (1989).

Speaking of cameos, let’s close this whole thing out with the final performance (so far) of a Beatle playing a character in a theatrically-released feature film. Paul pops up for a few minutes in Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Men Tell No Tales (2017), the fifth installment of the diminishing-returns Disney film series. He plays “Uncle Jack,” the namesake of Captain Jack Sparrow (Johnny Depp).

Depp originally based Sparrow’s slurred speech and fey, courtly mannerisms on Rolling Stones guitarist Keith Richards. Therefore, it made sense for Keith to appear as Jack’s father in the third movie, At World’s End, because there was a direct connection between Depp’s performance and Keith’s persona. Keith always carried a whiff of piracy about him, with his bandanas, silver jewelry, weatherbeaten face, and general air of outlawry.

None of that applies to Paul. Someone just figured one classic rock legend was as good as another, and stuck him in the movie without further thought. Paul once again bares his lack of acting chops, and does little more than be “Paul McCartney in a fake beard.” His presence has none of the resonance that Keith brought to his role due to that crucial bit of inspiration Johnny Depp took from him. (Plus, I suspect Keith is actually the better actor.) But what the hell, it’s just a fun little cameo.

Paul and Ringo let go of any real acting ambitions decades ago, and these days just concentrate on doing what they do best.

Broad Street station was demolished in 1986 and replaced by a shopping/office complex called Broadgate.

Denis O’Brien lived far too long, finally snuffing it in 2021.

And our happy ending — Ringo and Barbara Bach entered rehab in October of 1988 for a six-week treatment for alcoholism, and have been clean and sober ever since.