“Ringo liked films, but I think he just liked being in a Hollywood movie sort of world…he didn’t stop to say, ‘Hang on, I’m Ringo Starr. I have to choose carefully.’ He just did [the films] because they were good fun. Having a little laugh, you know? You get doomed for that, forever. People remember them.”

–Ray Connolly, That’ll Be The Day screenwriter

Ringo had a fairly successful follow-up album to 1973’s smash hit Ringo with 1974’s Goodnight Vienna. It reached a respectable #8 on the Billboard album chart, and its accompanying single “No No Song” got to #3 on the singles chart. But he couldn’t resist the allure of hanging out and having a little laugh on a film set.

It’s been so long since I left this website series hanging, I had to re-watch Lisztomania. The things I do…

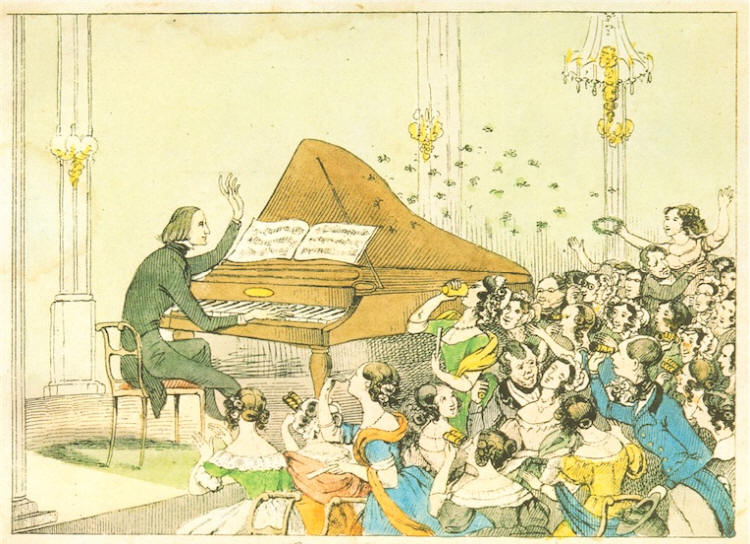

The term “Lisztomania” was coined by German writer Heinrich Heine to describe the effect composer and pianist Franz Liszt (1811-1886) had on an audience — mostly an audience of women. They would leap to their feet, scream, and sometimes faint. Liszt would rile them up, pounding out aggressive arpeggios, tossing his sweat-soaked hair, and distributing tokens such as scarves and gloves into the ecstatic crowd. It was the exact same effect that would crop up over a hundred years later in response to Elvis Presely and the Beatles.

Franz Liszt was the first rock star.

Director Ken Russell spun that single idea into a film that was as tedious as it was tawdry, its incoherence masquerading as “surrealism.”

But that’s Ken Russell for you.

“Lisztomania” cartoon by Adolf Brennglas, 1842

Franz Liszt was born in Hungary (thanks to some later border shifts, the town of his birth is now in Austria) and was considered a child prodigy. He studied under Antonio Salieri (yes, the Amadeus guy) and was said to have impressed both Beethoven and Schubert when he made his performing debut in Vienna at age 11. He subsequently lived for many years in Paris, composing, performing, and tutoring. He became personal friends (or sometimes “frenemies”) with fellow composers Felix Mendelssohn, Robert Schumann, Frederic Chopin, and most notably, Richard Wagner.

As he grew to adulthood, his chiseled features and flowing locks earned him many female admirers, but his reputation as a rabid womanizer was probably a little exaggerated. He was something of a serial monogamist, engaging in safe, long-term affairs with titled women in arranged marriages to indifferent (read: probably homosexual) husbands. One of these relationships, with Comtesse Marie d’Agoult, produced three children in the 1830s — daughter Blandine, son Daniel, and daughter Cosima, who later married composers Hans von Bulow and Richard Wagner in quick succession.

The “Lisztomania” period made up only a small portion of Liszt’s remarkable life. For seven years (1841-1848), he barnstormed the concert halls of Europe as a traveling virtuoso, selling sex appeal as much as music. He then quit performing to focus on composition, publishing the first of his Hungarian Rhapsodies and Liebesträume (“Dreams of Love”) in the early 1850s. He became the court conductor and choirmaster in the city of Weimar, Germany, a very settled-down and respectable position.

Liszt finally decided to marry for the first time to Princess Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein — who was, as usual, already married to someone else. He and Princess Carolyne spent over a decade trying to get her marriage annulled, to no avail. Even a sympathetic audience with Pope Pius IX in 1860 did not yield positive results in the end.

Pius IX (1792-1878) is known to history as the longest-serving pontiff. His leadership of the Catholic Church spanned 32 years, from 1846 to his death in 1878. He was initially a progressive supporter of church reform, but radical events such as the Revolutions of 1848 turned him more conservative. He orchestrated the literal kidnapping of a Jewish boy on the basis that he had been secretly baptized by a servant. Edgardo Mortara lived under “papal protection” until adulthood, despite the desperate pleas of his parents. The story brought waves of outrage, and contributed to Pius IX’s loss of the Papal States (a region of central Italy which the Pope had ruled directly as a sovereign monarch since 756).

Liszt and the princess gave up their attempts at matrimony. Liszt decided to become a monk, joining the Third Order of Saint Francis. He received a tonsure, and became Abbe Liszt. He still composed on a small piano in his monastery quarters. After almost a decade of cloistered life, Liszt returned to the wider world and bounced between Rome, Weimar, and Budapest, teaching master classes in piano. He never fully recovered from a fall down a staircase in 1881, and died five years later at the age of 74.

All of this is thrown into a cinematic blender by Ken Russell, along with celestial rocket ships, Nazis, vampires, superhero costumes, Nietzsche references, rayguns, and a ten-foot penis. (Not for nothing was one of Russell’s biographies titled Phallic Frenzy: Ken Russell and His Films.) “My film isn’t biography,” said Russell in the understatement of the year. “It comes from the things I feel when I listen to the music of Wagner and Liszt and when I think about their lives.”

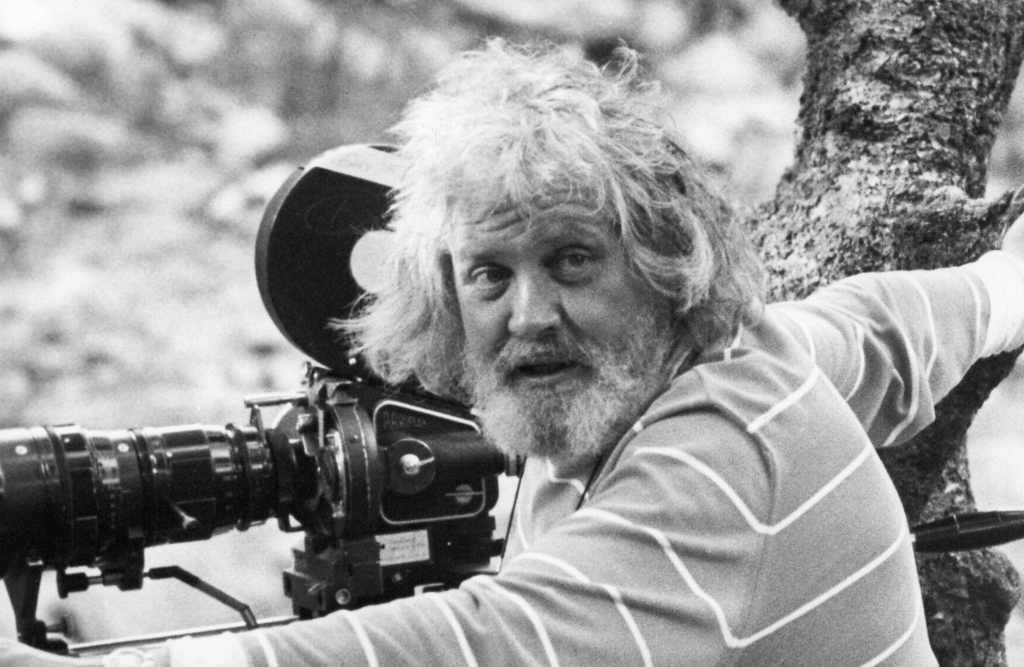

Ken Russell was an authentic English eccentric. Born in 1927, his childhood ambition was to be a ballet dancer. Rather than sell shoes in his emotionally abusive father’s shop, Russell opted for disastrous stints in the Royal Naval College and the British Merchant Navy. When he washed out of the latter, he reluctantly returned to the parental home. One day his mother and a friend came home early and discovered a teenaged Russell frolicking around the house in the nude to Stravinsky’s Rites of Spring. There were embarrassed faces all around, and an ultimatum — sell shoes or join the RAF. It was an easy choice.

After being discharged from the RAF in 1948, Russell decided to make his childhood dreams come true. He was actually accepted into the International Ballet School in South Kensington, mostly because he was one of the few male applicants. It didn’t take long for Russell to discover the flaw in his dream — he was a terrible ballet dancer. The Institute patiently kept him on for four years before they finally, and no doubt with a certain degree of exasperation, asked him to leave.

After making ends meet as a freelance photographer and a bit player in touring musical comedies, Russell was hired by the BBC to work in their documentary department based on a few independent short films he had made. One of his early assignments was a documentary on the composer Sergei Prokofiev.

The BBC had a very strict policy regarding documentaries. No actors, no “dramatic re-enactments.” It was to be only narration played over authentic photos, talking-head interviews with experts in the field, and, if available, archival footage. The iconoclastic Russell kicked against this policy from the get-go, and went ahead and inserted brief bits recreated by actors — hands on a keyboard, a reflection in a pond, that sort of thing. Despite admonishment from the BBC suits, he took it even further with his next composer biography on Edward Elgar. This was the beginning of a leitmotif in Russell’s career — a series of biographical films on composers. From relatively staid documentary works for BBC arts shows like Omnibus and Monitor in the 1960s to the twisted, overbaked cinematic explosions of the 1970s, Russell always returned to presenting the lives of composers.

Russell made his big cinematic breakthrough with an acclaimed adaptation of D.H. Lawrence’s Women in Love in 1969. Conventional compared to his later works, Women in Love still broke boundaries, featuring the first full frontal male nudity in a mainstream film. The naked wrestling match between Alan Bates and Oliver Reed certainly got the film a lot of attention…and repeat viewing. His next two composer biographies, The Music Lovers (1971) about Tchaikovsky, and Mahler (1974) reflected Russell’s increasing self-indulgence and reliance on surrealism. “More interested in impressionistic history than literal truths,” is how Russell biographer Joseph Lanza generously put it.

Russell’s flamboyant, overblown style was already familiar enough to be parodied by Monty Python in 1972.

To be fair, Russell always did meticulous research and did throw in small nuggets of historical accuracy as long as they were suitably weird. For example, Princess Carolyne really did smoke cigars and really did write a 24-volume work entitled The Inward Reasons for the Church’s Outward Weaknesses as depicted in Lisztomania.

Mahler was the first of a proposed six-film series on composers to be written and directed by Russell and produced by David Puttnam’s company Goodtimes Enterprises. It was to be followed by a film about Franz Liszt, for which Russell initially envisioned Mick Jagger as the star.

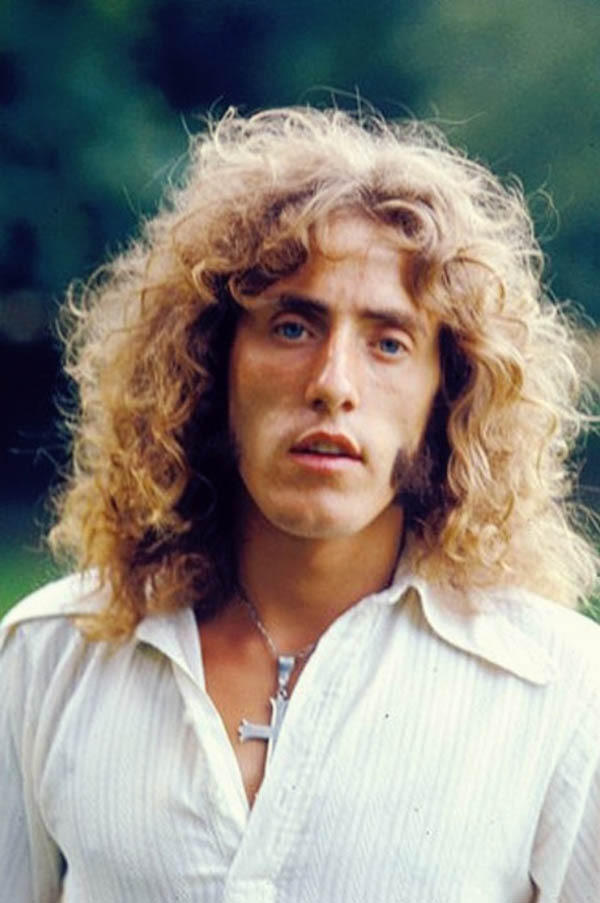

Before he jumped into the Liszt biopic, Russell decided he wanted to adapt the Who’s “rock opera” Tommy. The work was first released by the Who as a concept album in 1969, and performed by them as a three-piece band in opera halls as well as the usual rock venues across Europe and America. Classical music purist Russell was no fan of rock, but hearing the London Symphony Orchestra perform the Tommy material in true classical style in 1972 piqued his interest. He got in touch with Who guitarist/songwriter Pete Townshend, and the two hit it off and agreed to collaborate. It seemed only natural to cast Who lead singer Roger Daltrey as the title character. Tommy (1975) was a critical and box-office success, although I suspect the Who’s music and appearances by Elton John, Tina Turner, and Eric Clapton were more of a draw than Russell’s typical high-camp hallucinatory style.

At some point during the production of Tommy, Russell made a mental switch from Jagger to Daltrey for the role of Franz Liszt, and announced him as the lead in what was now called Lisztomania a month after Tommy had wrapped. Russell felt that Lisztomania would be a true companion piece to Tommy, exploring similar themes.

Allegedly, Ringo was cast in the film at the insistence of producer David Puttnam, who had also produced Ringo’s lone solo acting triumph, That’ll Be The Day (see Part Four), and wanted another major rock star name in the cast, a strategy which had worked well for Tommy. Puttnam’s other major contribution was hiring Rick Wakeman, who needed a break from boring people the world over as the keyboardist for somnambulistic prog-rock band Yes, to compose the score. (He also cameos as a mechanical Viking.) Cameras started rolling on Lisztomania at Shepperton Studios outside of London on February 3, 1975, just before Tommy hit theaters.

LISZTOMANIA

Released: October 10, 1975

Director: Ken Russell

Producers: David Puttnam, Roy Baird

Screenwriter: Ken Russell

Studio: Warner Brothers

Cast: Roger Daltrey, Sara Kestelman, Paul Nicholas, Fiona Lewis, Veronica Quilligan, Ringo Starr, John Justin, Andy Reilly, Nell Campbell, Rick Wakeman

This is the part I’ve been dreading. How can I possibly do a synopsis of this disjointed, unhinged spattering of a movie? The skeletal frame of the story is Liszt’s friendship turned rivalry with Wagner (Paul Nicholas), and Liszt’s attempts to balance his lustful nature with his dedication to both music and religion. Wagner, despite being a protege of Liszt’s, is repelled by Liszt’s showmanship and lifestyle, believing he is destroying the purity of the music.

Liszt’s relationships with both Marie d’Agoult (Fiona Lewis) and Princess Carloyne (Sara Kestelman) are heavily featured. Subplots include his guilt over his failure to participate in the May Uprising of 1849, and his daughter Cosmina turning against him and marrying Wagner, who has become a dangerous cult leader. Far from being the love of his life, Princess Carolyne is depicted as a demonic succubus in a dream sequence featuring Liszt and the aforementioned ten-foot penis.

Ringo appears in two scenes as Pope Pius IX. Like anything in Lisztomania, Ringo’s portrayal of Pope Pius IX has little to do with historical reality. The 34-year-old Ringo portrays the 68-year-old pontiff in his usual style — a rather flat delivery in his undisguised Liverpool accent. His first appearance is in disguise, as a hooded monk with an eyepatch, telling Liszt that the question of Princess Carolyne’s annulment has not been decided. Liszt seems relieved.

His second appearance is more impressive. After Liszt has taken the holy orders, the Pope glides into Liszt’s sleeping quarters on his sedia gestatoria (papal throne) accompanied by a retinue of cardinals and nuns, busting a contrite Liszt with a naked female companion (Rocky Horror Picture Show’s Nell Campbell). Here Ringo does manage to infuse the role with a little bit of a wry twinkle. Liszt isn’t in that much trouble for sneaking in a girl. The Pope has bigger fish to fry.

The Pope informs Liszt that his daughter Cosmina has married Wagner, whom he describes as “the Antichrist” and “Satan himself.” He tasks Liszt with performing an exorcism on Wagner, or else he will ban Liszt’s music. No good Catholic should hear the compositions of the Devil’s father-in-law.

He is attired in some of the most outrageous papal regalia to ever be imagined, including spurred cowboy boots and a headdress that must have weighed ten pounds. His vestments are embroidered with pictures of old Hollywood celebrities, Judy Garland most prominently across his chest. (As you can tell by the pictures, there are more deliberate anachronisms in Lisztomania than you can shake a ten-foot penis at.)

The set design and costumes are predictably over-the-top, with Liszt’s performance gear based heavily on Liberace (complete with candelabra on the piano). Wakeman’s score consisted of synthesizer adaptations of Liszt and Wagner pieces. It would be the first film with a Dolby Stereo optical soundtrack. “The film was rocketing over budget and every time I got back from raising money, the budget had gone up again,” said Puttnam. “The problem was he [Russell] never finished his screenplay, and frankly, he just seemed to go off his rocker.” Russell would stride around the set in his Mickey Mouse t-shirt, sandals, and a great coif of flyaway white hair, picking out tiny details to be changed, and not engaging with the actors at all, unless it was to verbally abuse the female ones (as reported by Fiona Lewis).

I’ll let the last two paragraphs of Wikipedia’s summary do some heavy lifting for me:

Liszt travels to Wagner’s castle, where Wagner and Cosima perform a secret Nazi ritual dressed in Superman costumes. Liszt confronts Wagner, who built a mechanical Viking Siegfried to rid the country of Jews. Wagner reveals himself to Liszt as a vampire and threatens to steal his music so that Wagner’s Viking can live. Liszt plays music to exorcise Wagner. Cosima imprisons Liszt and resurrects Wagner in a Nazi ceremony as a Frankenstein-Hitler wielding a machine-gun guitar. Cosima leads the Wagner-Hitler to gun down the town’s Jews and kills Liszt with a voodoo doll.

In Heaven, Liszt is reunited with the women he romanced in his life and Cosima, who live in harmony. Liszt and the women fly to Earth in a spaceship to destroy Wagner-Hitler. Liszt sings that he has found “peace at last.”

The End.

Can’t wait to see it? It’s only a $2.99 rental on Amazon Prime. I’ve done it twice, so clearly I hate the world and myself.

Lisztomania hit theaters in October of 1975 (a mere seven months after Tommy) and was not well-received. As per the New York Times: “For Mr. Russell, the shortest line between two points is a pretzel, preferably painted gold and doped.” I think that sums it up as well as anything

Ringo’s divorce from Maureen, his wife of ten years, in July of 1975 seemed to trigger a downward spiral for the drummer. Always a hard partier, his lifestyle now took on an edge of desperation. The final dissolution of the Beatles’ business partnership in January freed up millions in frozen assets and he burned through money like water, hiring private jets, buying tons of jewelry for himself and his post-divorce girlfriends, and gambling in the casinos of Monte Carlo (where he had a luxury condo). All fueled by a never-ending stream of top-shelf brandy, champagne, and cocaine. His next album, Ringo’s Rotogravure, was a flop. He was newly signed to Polydor Records, and they may have had second thoughts. “Ringo just seemed content to let the producer lay down some backing tracks for him and then he would pop in from Monte Carlo and just stick on his vocals,” said Polydor executive (and former Beatles publicist) Tony Barrow.

In the summer of 1976, just after finishing the recording of Rotogravure, he had a complete nervous breakdown, shaving off his beard, hair, and eyebrows. “It was a time where you either cut your wrists or your hair, and I’m a coward,” Ringo said later. “I ended up as just some fucking celebrity. I’d be at movie premieres in London with my bow tie on and a bottle of cognac in my pocket…it got really sad.” Maybe doing another just-for-the-hang movie role would fill the void.

In late 1976 (hair all grown back) he was offered a part in the Mae West film Sextette.

Wait…Mae West? The sassy blonde bombshell of the 1930s? W.C. Fields’ co-star? She was still doing movies in the late 1970s? Regrettably, yes.

Mae West was born in Brooklyn in 1893. She started in vaudeville as a child performer known as “Baby Mae,” and was singing and dancing on Broadway by age 18. She bounced between vaudeville and Broadway through the 1910s and early 20s.

At a certain point, performing other people’s material could no longer contain her ambition. In 1926, she wrote, produced, and starred in her own Broadway play about a prostitute and a pimp. Deciding not to play coy about it, she simply titled it Sex. The show eventually landed her in jail on obscenity charges. (She served eight days, and it was great publicity.) She followed Sex with The Drag, which featured homosexual themes. Several more racy and controversial plays followed, culminating in her huge hit, Diamond Lil, in 1928. It was Diamond Lil that finally cemented her performing persona — the seductive manner, the hip-swaying walk, and the sly, insinuating wisecracks that she purred from the side of her mouth.

Hollywood came calling. She played opposite a young Cary Grant in a 1933 adaptation of Diamond Lil, re-titled She Done Him Wrong (and featuring her famous line “why don’t you come up sometime and see me?”). Films like I’m No Angel, Klondike Annie, and Go West, Young Man followed through the 1930s. She wrote or co-wrote all of them. Most of them ran into trouble with the censors.

Her collaboration with W.C. Fields, 1940’s My Little Chickadee, is considered the end of her relatively brief film career. She was pissed that Fields received a co-writing credit for a single scene and some of his own dialogue (the duo reportedly despised each other), and critics were not kind about her performance. She never had much acting range beyond her Diamond Lil persona, and the schtick was wearing thin. By now pushing 50, West did one more turn as a glamorous diva in 1943’s The Heat’s On.

Through the rest of the 1940s she was offered numerous parts (so she said), but rejected them all because they were roles for “older” women. She did a popular lounge act in Las Vegas in the 1950s, and toured several of her old plays in summer stock. In 1961, she opened a new play, her final self-penned stage production: Sextette (“based on a story idea by Charlotte Francis”). The premise: mega-famous movie star Marlo Manners is trying to have a romantic honeymoon with her sixth husband, but their attempts to consummate the marriage keep getting interrupted by visits from her ex-husbands. The play opened in Chicago, toured all that summer, and closed in Miami. It was a financial success, and got decent reviews.

Here’s West biographer Simon Louvish: “Anyone else might have rested on these laurels, bowed gracefully and retired to the shadows of ceremonial dinners, tributes of her peers, movie revivals, tending the garden, chuckling wistfully over the old scrapbooks. But not Mae West…Baby Mae was still not ready to leave the spotlight, even if her sight might blur, her make-up thicken, her wigs slide off, her gait begin to falter. Immortality imposed its own obligations, and the performer’s duty still called.”

West’s groundbreaking career as one of the first major female playwrights/screenwriters, her championing of sexual frankness on stage and in cinema, and her battles against censorship made her a legend and a feminist icon. But she seemed bound and determined to squander that legacy by insisting on presenting herself as an eternally youthful sexpot, despite all sensory evidence to the contrary. By the time of her “triumphant” return to the screen in 1970’s sex-change comedy Myra Breckenridge, she was a frail, elderly woman slathered in make-up, gazing vacantly from behind huge Tammy Faye-style false eyelashes, and repeating the same tired Diamond Lil quips and double-entendres that had been in her act for forty years. (Myra Brenckenridge was its own special cinematic drool cup that will merit no further mention here as no solo Beatles were featured in it.)

Plans for a screen version of Sextette were underway as early as 1969, but — understandably — there was trouble raising money to produce it. Evidently, at least two people wanted to see it made. Daniel Briggs and Robert Sullivan, a pair of eager young Mae West fans, formed a production company (“Briggs & Sullivan”) and somehow managed to scrape together several million dollars through the early 1970s. Herbert Baker, writer of several Martin & Lewis movies (and a writer on The Dean Martin Show), was brought in to adapt West’s play. West remarked “[Baker]’s putting in the camera shots. I can do that, but it’s tedious work. He’s not writing my lines, though. Nobody can do that.” Baker actually fleshed out the somewhat flimsy play with a few subplots about a peace summit, some espionage, and a lost tape recording.

After a declined overture was made to classic Hollywood director George Cukor (The Philadelphia Story, My Fair Lady), it was Irving Rapper (Now, Voyager, The Glass Menagerie) who was hired to direct. Briggs & Sullivan somehow managed to convince eight-time Oscar winner Edith Head to do the costumes. (She had done several of West’s old movies back in the day, so maybe she succumbed to nostalgia.)

It was to be a glamorous, all-star cast (or as near as they could get to it), except for the part of the sixth husband, for which they wanted a young, handsome, and relatively unknown actor. Over a thousand actors auditioned, and the role went to future James Bond Timothy Dalton. Ringo was cast as one of the ex-husbands. And, as usual, wherever Ringo went, Keith Moon was bound to turn up. According to Ringo’s friend Keith Allison, the producers dropped by Ringo’s rented Hollywood house to discuss something with him, and Moon happened to be there. The ubiquitous Moon was given a role in the film as a swishy fashion designer, once again playing the part of Ringo’s cinematic shadow. (The production also tossed Allison in as a hotel bellhop.)

Two weeks before production, Irving Rapper was replaced with journeyman British director Ken Hughes (Chitty Chitty Bang Bang). No source I’ve uncovered gives a reason. Perhaps Rapper saw a disaster brewing and bailed. Shooting started at Paramount Studios (one source says the Samuel Goldwyn Studio) in December of 1976. For all the statements about Ringo getting the acting bug and “going Hollywood” in the 1970s, this was his first movie that was actually shot in Hollywood.

SEXTETTE

Released: March 2, 1978

Director: Ken Hughes

Producers: Daniel Briggs, Robert Sullivan, Harry Weiss

Screenwriter: Herber Baker, based on the play by Mae West

Studio: None (Briggs & Sullivan production company; distributed by Crown International Pictures)

Cast: Mae West, Timothy Dalton, Dom DeLuise, Tony Curtis, George Hamilton, Ringo Starr, George E. Carey, Peter Liapis, Alice Cooper, Keith Moon, Walter Pidgeon, Van McCoy, George Raft.

The film opens not in Hollywood, but in London (well, second-unit footage of London) where movie star Marlo Manners (Mae West, in her final role) has just married for the sixth time to young British nobleman Sir Michael Barrington (Timothy Dalton). The occasion is breathlessly reported on by Regis Philbin, one of several media personalities playing themselves. The happy couple check into a luxury hotel in front of cheering, adoring fans. Also occupying the hotel at the same time is an “international conference” of diplomats who are trying to resolve multiple global issues. Topping it all off is the arrival of the non-specific “U.S.A. Athletics Team,” looking as beefy and masculine as possible in that horrible 70s way, with porno mustaches and poofy hair.

As Marlo and Sir Michael try to get their honeymoon kicked off, the international conference grinds to a halt as all the members stop to gawk at the (supposedly) sexually irresistible Marlo. The chairman (Walter Pidgeon, in his final role) tries to get things back under control, to no avail. Also, the Russian delegate, Alexei Karansky (Tony Curtis), happens to be one of Marlo’s ex-husbands and is threatening to derail the whole conference unless he gets one last night with Marlo.

The demands of her career keep the marriage from being consummated. Marlo’s manager Dan Turner (Dom DeLuise) also lusts after her, but keeps his feelings mostly in check as he continuously barges into the honeymoon suite to pull her away for things like a dress fitting with a seemingly insane designer (Keith Moon, in his final role). (The dresses were all based on ones worn in West’s old movies. There are reportedly a number of Easter egg nods to West’s career hidden through Sextette.)

The incomparable Keith Moon

Then there’s a potential top secret tryst with “Sexy Alexei” to help bring about world peace. It seems that Marlo Manners is also a secret agent for the U.S. government, specializing in “honeytraps.”

Ringo shows up as the demanding, dictatorial Hungarian director Laslo Karolny, another ex-husband, complete with beret, jodhpurs, and a viewfinder dangling from his neck. Karolny demands a “test footage” shooting session with Marlo and a potential young co-star (Peter Liapis), chosen deliberately for his inexperience so Karolny can shove him out of the way and demonstrate the romantic scene himself (yes, Karolny still has an overwhelming desire for Marlo).

Ringo still cannot manage to hold onto an accent past his first few lines, but his hysterical (in the crazy sense, not the funny sense) performance otherwise suits the campy material. Another ex-husband, pin-striped gangster Vance Norton (George Hamilton), pops up, wanting to…

Oh, forget it. I had lost all higher cognitive functions at this point in my viewing. By the end of the film, according to my rough estimate Marlo has driven around twenty men to sexual frenzy with her mere presence, including the entire U.S.A. Athletics Team, who are all played by freakishly over-muscled bodybuilders (a Mae West fixation going back to her lounge act days), regardless of the sport they are supposed to represent.

There’s also the lost audio tape of Marlo dictating her memoirs, which is deemed too scandalous to let fall into the wrong hands, and George Raft (in his final role) cameos as himself, riding an elevator with Marlo. In just one example of Ken Hughes’ sloppy direction, the elevator doors clearly never close. The pair just stand there exchanging inane witticisms until Raft gets off on the same floor he started from. (Raft was West’s first cinematic co-star in 1932’s Night After Night.) And in an amazing coincidence, Timothy Dalton’s character turns out to be a British secret agent! Dan Turner even compares him to 007.

World peace is achieved, and Marlo and Sir Michael finally bed down together on Sir Michael’s yacht. Marlo’s last line — “The British are coming!” — is actually one of the better jokes.

West was a wobbly, slightly cross-eyed, frozen-faced 83-year-old husk of her former self at the time of production. (Her age in Sextette has been inaccurately reported as anywhere from 84 through 87. George Raft swore she was over 90.) Her deafness forced her to wear a radio earpiece so her lines could be fed to her. (Tony Curtis said there was occasional cross-traffic, causing West to recite L.A. police calls and taxi dispatches. Ken Hughes denied this.) None of this stopped her from making passes at any man that crossed her fading field of vision. Alice Cooper had a small part as a piano-playing waiter, and revealed that West had invited him back to her trailer. “If I hadn’t been married, I would have gone. Definitely. Just for the experience,” Cooper recalled later. “She tried it twice on me,” confirmed Ringo. “I didn’t mind really.”

There are certain moments where you wonder what you’re doing with your life. Sitting in front of my computer screen at one in the morning watching a young James Bond warble a version of Captain & Tennille’s “Love Will Keep Us Together” to an embalmed, octogenarian zombie-woman in a towering wig was one of those moments for me. (Did I mention Sextette is allegedly a musical? We’re also treated to Dom DeLuise prancing around singing the Beatles’ “Honey Pie.”)

As I watched, poleaxed, I kept thinking this had to be self-parody and maybe my irony detector was broken. But no, all indicators point to West taking this very seriously, firmly believing she was, in fact, Marlo Manners. Sextette is a charmless, nearly-unwatchable monument to one person’s ego and inability to make a graceful exit.

Once filming was completed, Briggs & Sullivan labored for almost a year trying to find a distributor. No respectable studio would touch it. Low-budget specialists Crown International Pictures finally shrugged and figured what the hell. (Almost every film on their roster would one day be the subject of a Mystery Science Theater 3000 episode.) They did a slow roll-out beginning in March of 1978.

The reaction was predictable. “Sextette is a disorienting freak show,” said critic Vincent Canby. “The character we see looks less like the Mae West one remembers…than like a plump sheep that’s been stood on its hind legs, dressed in a drag-queen’s idea of chic, bewigged and then smeared with pink plaster. The creature inside this getup seems game but arthritic and perplexed.” “He [Dalton] looks 25, she looks like something they found in the basement of a pyramid,” said Rex Reed. “It will probably be shown decades hence as a monument of ghoulish camp.” (Incidentally, Rex Reed is something of a monument of ghoulish camp himself.)

After an $8 million (estimated) outlay netted them about $50,000 at the box office, neither Briggs nor Sullivan were ever heard from again.

Ringo’s downward spiral continued. His next two albums tanked, and his label dumped him. An NBC TV special also failed, despite co-starring Carrie Fisher and John Ritter, hot off of Star Wars and Three’s Company, respectively. Not even a special appearance by George Harrison could save it. He spent a week in intensive care after having five feet of small intestine removed from his ravaged system. His pal Keith Moon died in September of 1978 (ironically of an overdose of medication meant to curb his alcoholism).

Then…a film offer came. Good money. A respected screenwriter’s directorial debut (Carl Gottlieb of Jaws fame). Location shooting in sunny Mexico. Most importantly — the long-desired leading role!

Could this turn it all around?

No. No, it could not. In fact, it ended Ringo’s movie career.

[End Note: The deal with Goodtimes was cancelled, and Lisztomania was Ken Russell’s final composer biopic. He did a few more interesting pictures (most notably 1980’s Altered States with William Hurt) and quite a few more turkeys. His career was pretty much over after 1991’s Whore starring Theresa Russell (no relation). He died in 2011. Mae West had a series of strokes through the summer and fall of 1980, two years after Sextette’s release (or escape). She died watching films of herself projected on the bedroom wall of her Hancock Park apartment on November 22. George Raft died two days later.]