Prologue: Ringo As Director?

The Beatles’ many-faceted multimedia company, Apple Corps, continued in spite of the split between its four creators. Like all the ex-Beatles, Paul was contractually tied to Apple Records (via Capitol) through the end of 1975, but otherwise wanted nothing to do with the business that had driven such a wedge between himself and the other three. John, George, and Ringo continued to use Apple as a creative playground for the next few years.

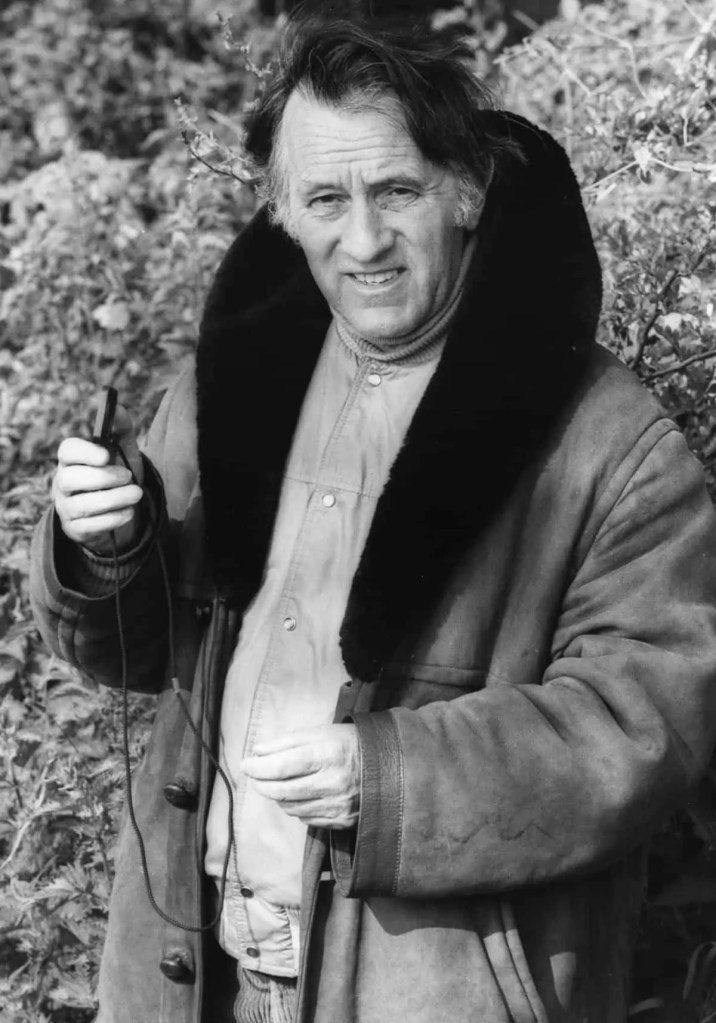

Since the Beatles’ break-up, Apple Films had managed to release two George Harrison-produced documentaries: his own concert film, The Concert for Bangladesh, and an exploration of the music of Ravi Shankar, Raga. Apple Films had been nominally under the supervision of Denis O’Dell (also producer of The Magic Christian, see Part 2) since 1968, and it’s only natural that the movie-minded Ringo gravitated to this subsidiary of the company. O’Dell had one foot out the door by 1971, and Ringo pretty much took over, using the Apple Films office as his personal headquarters and clubhouse. Joined by the ever-present Keith Moon and Harry Nilsson, the Apple Films office on St. James Street often served as the starting point for a long night of carousing around the nightclubs of London.

Sometime in the second half of ‘71, Ringo made the acquaintance of Marc Bolan, frontman of the band T. Rex. Their single “Get It On” had burned up the U.K. charts that summer, and their classic album Electric Warrior — often credited as the first “glam rock” album — was about to drop. They were riding a crest of huge popularity in Britain (described in the music press at the time as “T. Rextasy”).

“I don’t know how he got in there,” says Ringo, whose memories of that era are understandably fuzzy. Ringo was charmed by the elfin, enigmatic songwriter and he was quickly included in the hard-partying drummer’s social circle. (The title and lyrics of Ringo’s 1972 single “Back Off Boogaloo” were inspired by Bolan’s cheery space-hippie nonsense sayings.)

When T. Rex played two shows to a combined 20,000 Rextatic fans at one of Britain’s largest venues, Wembley Arena (then known as “Empire Pool”), on March 18, 1972, Ringo decided to hire a film crew to capture the event for posterity. He eagerly clambered down into the photographer’s pit at the front of the stage and began calling the shots, even occasionally operating a film camera himself. The additional footage in the DVD release of the resuting film Born To Boogie shows that Ringo captured plenty of useable footage for a traditional concert film — but, alas, he had other ideas.

Ringo switched hats from documentarian to surrealist. “My theory about filming concerts is you can’t capture the atmosphere that was in the hall,” he explained. “So I needed to do more.” He and Bolan concocted a couple of fantasy sequences to make the film more of a visual experience. The scenes were both heavily inspired by the Beatles’ own hot mess of a 1967 TV movie Magical Mystery Tour. One, set on the runway at Denham Aerodrome, seemed pretty improvised — Bolan goofing around in a red convertible, joined by a Ringo in a mouse suit and an angry little person in a Dracula cape who proceeds to eat various parts of the convertible. The other sequence showed evidence of more planning — a fancy tea party turned carnivorous hamburger cookout, complete with a tuxedoed waiter, violinists, and nuns. Bolan as the Mad Hatter treats us to gentle acoustic versions of “Jeepster” and “Get It On” (neither of which work in this format), along with two other songs. This particular sequence was filmed around the lakes of John Lennon’s massive estate, Tittenhurst Park. (John had moved to the U.S. the previous August, and Ringo was designated as the property’s caretaker, until he bought it outright in 1973. Tittenhurst Park was also the setting for the last Beatles photo session in 1969 and John’s “Imagine” video in 1971.)

The fantasy sequences were exactly as wretched as you would expect, and show why surrealism shouldn’t be left in the hands of self-indulgent, drug-addled musicians. It’s always the same old sub-Fellini shit, featuring a lot of nuns, little people, and undercranking.

A non-concert segment that works slightly better is a jam session on a set heavily dressed with stuffed circus animals, giant toothbrushes, and tons of reflective foil paper filmed in Tittenhurst Park’s Ascot Studios. Joining T. Rex for renditions of Little Richard’s “Tutti Frutti” and their own “Children of the Revolution” are Elton John on piano, and Ringo on a second set of drums when he’s not randomly wandering in and out of shots in a clown costume and make-up. (The glimpses of the camera crew indicate they are also in full circus gear.)

Intercut among of all this dated, cringe-worthy hogwash is about forty minutes of decent T. Rex concert footage. In spite of the film’s issues, Ringo does demonstrate a natural feel for both photography and editing, and had he stuck with directing as a sideline, probably could have produced some truly quality work.

Apple Films premiered the 61-minute Born To Boogie in December 1972, with a wider release the following spring. “We made the film strictly for a teenage audience who demand youthful excitement at the cinema,” Bolan said. “I think the film does that — no more, no less.” The film came and went with little notice.

Bolan was killed in a London car crash five years later.

Ringo never returned to the director’s chair.

Computer programming was incredibly primitive in 1962. Room-filling computers running off of paper punch cards took hours to perform functions that a modern smart phone can do in a nanosecond. Security First National Bank in Van Nuys, California was an early adopter of computer tech — the first bank in the country to use magnetic coding on checks. A lot of the grunt work was done on the overnight shift by three massive computers ran by thirty-two sorters and operators. The whole team was supervised by a twenty-one-year-old Brooklyn-born high school dropout (he lied on his application), who also happened to be a musical prodigy. Existing on almost no sleep, he spent his daytime hours writing songs he hoped to have published.

His name was Harry Nilsson.

The problem, if you can call it that, was that everyone who heard him perform his songs loved his voice, and felt he should become a recording artist in his own right. He was cautiously amenable to this, but was terrified of performing in front of an audience. So his music career continued in fits and starts — he sold several songs to big-time producers, sang songs (his own and others) on demo recordings, and released a few independent singles of his own (usually under a pseudonym). Some of these early recordings were compiled into a low-key debut album on a budget label in 1966, and on the back of that, RCA signed him up.

His second album and first for RCA, 1967’s Pandemonium Shadow Show (credited simply to his mononym “Nilsson”), showed off his soulful voice, his original songwriting skills in a variety of genres (this was by no means a traditional “rock” album — Nilsson usually defied categorization), and his ability to give unique twists to songs by other artists, including the Beatles’ “You Can’t Do That.” The album became a critical favorite, and although it never sold in massive numbers, it was heard and admired by people who mattered. The Beatles themselves became huge fans. It was rumored he was paid $40,000 by the Monkees for one of his songs (“Cuddly Toy”). All without ever performing a live set.

When he heard the Monkees’ version of “Cuddly Toy” being played continually on the radio in the fall of 1967, he finally quit Security First National Bank.

Nilsson briefly met all the Beatles on a trip to England in 1968 while they were recording “The White Album,” and they promised to keep in touch.

He finally got the commercial success to go with his critical respect with the theme song to Midnight Cowboy, Fred Neil’s “Everybody’s Talkin’,” in 1969. That same year, Three Dog Night took one of Nilsson’s originals, “One (Is The Loneliest Number),” to the Top 5.

When Nilsson teamed up with well-respected producer Richard Perry to record his seventh album in 1971, Perry said the best engineer to work with to get the sound they were after was Robin Geoffrey Cable of Trident Studios in London. Nilsson was only too happy to make an extended stay in his “favorite city.” It was at this point he entered the bleary orbit of Ringo and Keith Moon (and sometimes Marc Bolan and Monty Python’s Graham Chapman), where it was brandy for breakfast, cocaine for dinner, sunglasses indoors at night, and the good times never stopped.

The resulting album, Nilsson Schmilsson, was his most commercially successful, yielding the epic #1 ballad “Without You” (a cover of Apple Records’ own discovery, Badfinger), the thumping rocker “Jump Into The Fire,” and the breezy novelty song “Coconut.”

When it came time to record a follow-up in the spring of ‘72 (Son of Schmilsson), a return to London and Trident Studios was an obvious choice. Ringo played on several tracks (credited as “Richie Snare”). The partying became more decadent, the partiers became more pale, bloated, and dissipated, and the album was not as successful as its predecessor. By then, Nilsson had separated from his wife and impulsively bought an apartment in London. For the next six years, he would divide his time equally between L.A. and Flat 12, 9 Curzon Square, Mayfair.

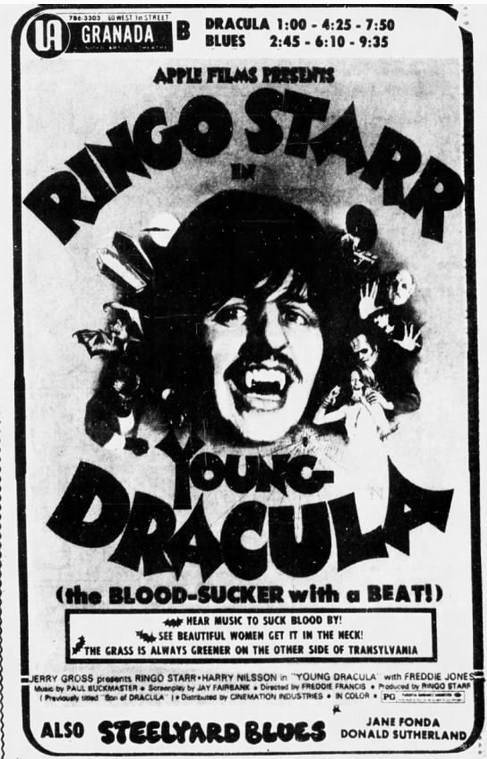

“Ringo and I spent a thousand hours laughing,” recalled Nilsson. At some point during their brandy-soaked bull sessions, Ringo mentioned an idea for a movie that had been rattling around his head for awhile. It would be a horror-rock-comedy about a reluctant vampire who would rather be a musician. The vampire’s name? Count Downe! That was the sole joke so far. Would Nilsson like to star in it? Nilsson assumed Ringo was spitballing based on the album cover of Son of Schmilsson, where Nilsson posed as Dracula. As it turns out, Ringo hadn’t even seen the cover of his best pal’s album that he had so recently played on. Starting from this speck of an idea, Nilsson agreed to participate and Ringo decided to produce the project through Apple Films, putting up $800,000 out of his own pocket.

The first thing they had to do was put together a script, and neither Ringo nor Nilsson had the tools, time, or desire to engage in the drudgery of screenwriting. So they found someone who came cheap — Jennifer Jayne. A mid-level actress of 1950s-60s British cinema and television, Jayne was trying to break free of her unfulfilling acting career to become a screenwriter under the pseudonym “Jay Fairbank”. Via circumstances I have yet to uncover, Jennifer Jayne was commissioned by Apple Films to quickly bash out a script based on Ringo’s one-sentence idea. The result bore all the hallmarks of hasty assembly by an amateur scribe. For something purported to be a “horror comedy,” there were neither scares nor laughs to be found. Not a-one. Ringo went ahead anyway. “We had this script, Drac [sic] takes the cure, marries the girl and goes off into the sunlight – and it was the only movie we wanted to make,” he said. Once the script — such as it was — was submitted, he got down to work.

“I went through everything,” said hands-on producer Ringo. “Casting, meetings with the actors, electricians, the lot. I wanted to make the film in England because it’s easier to learn at home.” Nilsson would play the leading role of Count Downe. “We had Harry’s teeth fixed, which his mother was always grateful for,” noted Ringo. Ringo cast himself as Merlin the Magician, and Suzanna Leigh would be the leading lady. Esteemed British character actors of that era were widely known to be 1) workaholics, and 2) desirous to fill their bank accounts so they could take artistically-fulfilling but lower-paying stage roles. Lots of them would take any film part, no matter how silly or demeaning, if the money was right and the schedule was brief. Two of them — Dennis Price and Freddie Jones — accepted the roles in the film. (In a stroke of luck, Price died shortly after completing his part, so he never had to live with the results.)

Another Freddie, Freddie Francis, was brought on board as director. Francis was an Oscar-winning (Sons and Lovers) cinematographer trying to make the transition to directing his own films. He was mostly stuck with the low-budget horror of Hammer Studios, and worked quickly and inexpensively.

Cameras began rolling on location in London in August of 1972. The first thing shot was Count Downe’s big performance sequence, done over two nights on the Surrey Docks. The backing band consisted of Keith Moon on drums, Peter Frampton on guitar, Klaus Voormann on bass, and Jim Price and Bobby Keys (fresh off recording the Stones’ Exile On Main St.) on brass. On the second night of filming, Moon was due on stage in Brussels with The Who, so Led Zeppelin’s John Bonham subbed in. “[The band] was costing me just union rate, only about 30 quid a day,” said Ringo. “But it was costing £1000 for booze! It was such a headache. Everyone shouts at you. I didn’t know that if you didn’t get your crew home and in bed by midnight, you couldn’t work them the next day. I’m a musician. If we start working and it starts to cook, we’ll keep it rolling for three days if necessary.” Further location shooting took place at Wykehurst Place (standing in for the exterior of Dracula’s castle) and Sussex Place in Regent’s Park (“Merlin’s house”). Presumably, there was plenty of soundstage work in a studio as well, but I couldn’t track down which one.

Filming wrapped in late October. Although Ringo gamely threw himself into the pre-production chores, now that the “new project” buzz had worn off, post-production seemed like a hassle and a bummer. A review of the finished footage revealed that it would require an enormous effort to get it even close to releasable shape.

No release or distribution plan had been devised by Apple Films. Ringo was due on the set of his next film project pretty much immediately, and everyone involved walked away and left Count Downe on the shelf for the time being…

“Well in 1941, a happy father had a son/And by 1944, the father walked right out the door”…

So go the lyrics of Nilsson’s autobiographical song “1941.” And they provided the impetus for Ringo’s next film project.

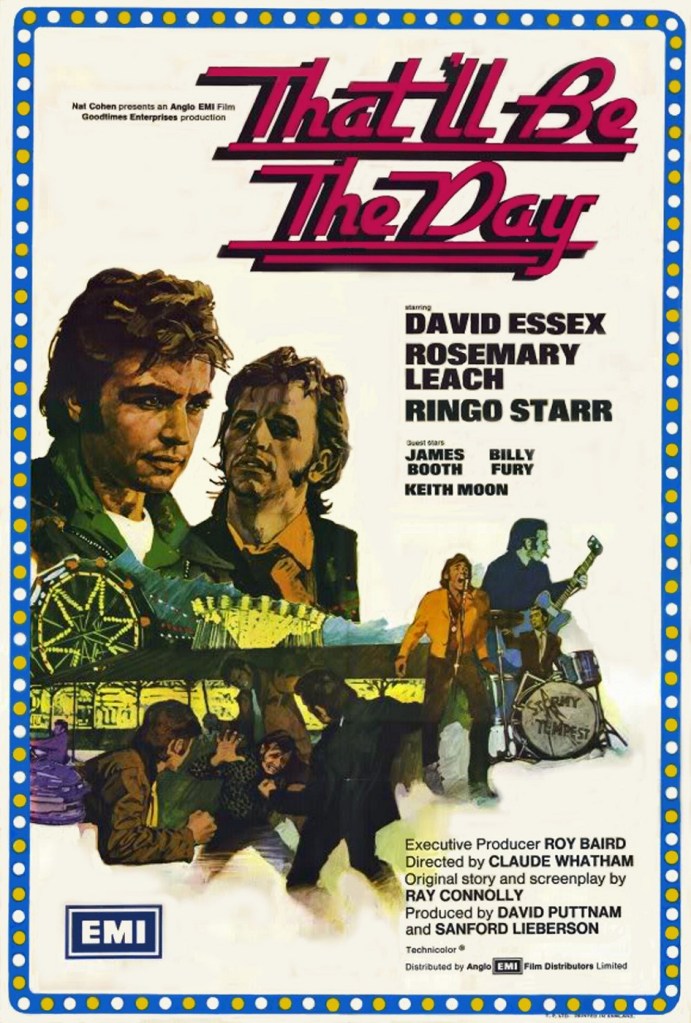

“I had a huge stroke of beginner’s luck,” recalled first-time screenwriter Ray Connolly. “Going over to a friend’s house to borrow a book, I was asked, over a cup of tea, if I would like to write a film. Just like that.” Connolly worked for the London Evening Standard, and was considered one of the fist true “rock” journalists in Britain. He had interviewed the Beatles many times in the 1960s, and knew them all well. His friend was David Puttnam, a former advertising executive who decided to try his hand at film producing. Puttnam was inspired by the Nilsson song, and pitched the idea of a coming-of-age story to Connolly.

“By the time I went home that afternoon, not only had we sketched out a vague plot, but we also had a title for our film,” said Connolly. That’ll Be The Day would be set over a few years in the late 1950s and early 1960s, when British kids were first discovering rock & roll. It would tell the story of Jim MacClaine, a fatherless youth who abandoned the drudgery of school and semi-respectability for the seedy world of seaside resorts, fun fairs, and holiday camps — lured by a life of personal freedom, sexual promescuity, and rock & roll music.

After a three-month writing process, Connolly admitted his script had a problem. The main character, Jim MacClaine, was thoroughly unlikeable. “[He] hardly did a decent thing in the entire story. He was the ultimate selfish teenager,” said Connolly. Unsure how to solve the problem without a complete square one re-write, Connolly took his problem to Puttnam, who fould what he believed was the solution.

David Essex had tried his hand as a teenage pop star in the 1960s, but never quite broke though. In 1971, at age 23, he landed the lead role in the West End’s long-running production of the musical Godspell, which is where David Puttnam saw him. Puttnam believed Essex’s good looks and charm would keep the audience’s sympathy no matter what he did. No re-writes needed. Essex was cast, and production moved forward. Media conglomerate EMI agreed to front some money…but it wouldn’t be enough.

Enter Ronco, Ron Popeil’s well-known “as-seen-on-TV” gadget company. Ronco agreed to put up a good chunk of money on the condition that they have exclusive rights to the film’s 1950s oldies soundtrack. “Ronco Records” could then hawk the resulting album on their late night TV commercials. In the immortal words of those same commercials, “But wait! There’s more!” Ronco demanded no less than forty songs on the soundtrack, and it was Connolly’s task to shoehorn them all in.

After several years of directing documentaries and TV dramas for Granada Television*, Claude Whatham would make his feature film directing debut on That’ll Be The Day. The production settled on the Isle of Wight as the ideal location, “because in the early ‘70s, it still had a late ‘50s look to it,” said Connolly.

Ringo was initially consulted as an informal technical advisor. Before joining the Beatles, he had drummed with Rory Storm and the Hurricanes for several seasons at a Butlin’s holiday camp during the same time period depicted in the film. His hilarious anecdotes about holiday camp life so charmed Puttnam and Connolly that they offered him a supporting role in the film.

In fact, a band based directly on Rory Storm and the Hurricanes was an important part of Connolly’s story. The resident band at the holiday camp where Jim finds work is called “Stormy Tempest and the Typhoons.” Billy Fury played Stormy. In the role of the energetic drummer, J.D. Clover (which would have been Ringo in real life), the producers cast Keith Moon. (Connolly initially intended to offer the role of either Tempest or Clover to Ringo, but after consideration, offered him the larger part of Mike Menarry.)

Ringo (far right) with the original Rory Storm and the Hurricanes, c. 1961

[SIDE NOTE: In the pre-Beatles British pop music world of the early ‘60s, manager and impresario Larry Parnes put together a stable of singers noted more for their youth and looks than any real talent — all with big pompadours, puppy-dog eyes, and passable voices. Parnes gave them stage names like “Marty Wilde,” “Vince Eager,” “Duffy Power,” “Dickie Pride,” and, yes, “Billy Fury.” The lowest rung on Parnes’ ladder was the slightly-older and less-handsome “Johnny Gentle.” He was thought so little of, Parnes agreed to hire a second-rate group of scrappy Liverpool amateurs with no full-time drummer to be his backing band on a short tour of Scotland in 1960. It was the pre-Ringo Beatles’ (or “Silver Beetles” as they were then known) first tour.]

Filming began on the Isle of Wight on October 23, 1972 and continued through November. Ringo came to the location hot off of the Count Downe shoot, clean-shaven with big sideburns, along with his own vintage 1950s clothes. “My part as Mike is total flashback since he’s very much me as I was in the late 1950s. [I even wear] my own actual velvet-collared jacket [from the period],” said Ringo. “Everyone reeled back from the smell of mothballs when I put it on. I wear a pair of socks I used to wear in those days too.” Connolly also noted Ringo took the ferry to the location like the rest of the cast and crew, but the “excessive” Moon arrived each day via helicopter, sometimes dressed as the Red Baron.

Since Ringo had actually lived the life being depicted, director Whatham allowed him to improvise. “[I could] ramble on all I wanted, because people write lines for you that you’d never say. So I did my own dialogue. I love it when they let me go off on my own.” (“There’s no future in being a Typhoon,” remarks Ringo’s character at one point.)

THAT’LL BE THE DAY

Released: April 12, 1973

Director: Claude Whatham

Producer: David Puttman, Sanford Lieberson

Screenwriter: Ray Connolly

Studio: EMI Films

Cast: David Essex, Rosemary Leach, Ringo Starr, Rosalind Ayres, Robert Lindsay, Billy Fury, Keith Moon, Beth Morris, James Booth

Jim MacClaine (Essex), a lower-middle-class high school student being raised by a single mother (Rosemary Leach), decides he doesn’t want the future of drudgery that seems to be destined for him. His best friend, Terry (Robert Lindsay) is much more comfortable with his life, and tries to be the voice of reason, to no avail. Jim impulsively tosses his school bag off a bridge into a stream, skips his university entrance exams, and runs away from home.

After an initial job sorting beach chairs on a typically gray and gloomy British seashore, Jim is hired as a barman at a holiday camp. His fellow barman, Mike Menarry (Ringo), is slightly older and decides to take Jim under his wing, at least as far as scoring with girls. (To our horrified modern eyes, Jim goes far beyond Mike’s tips, and his method of “scoring” looks a lot like “rape.”) Jim is also increasingly fascinated by the music being pumped out by the camp’s resident band, Stormy Tempest and the Typhoons. When the camp’s busy season ends, Mike tells Jim it’s time to move on to the carnival, where he shows him how to supplement his income by short-changing customers. This eventually backfires on Mike when he is caught cheating by a violent gang, who beat him within an inch of his life. Jim flees the scene. It’s unfair to judge Jim for what seems to be an act of cowardice (I don’t know if I’d stick around to share my friend’s vicious stomping), but after the fact, he turns his back on the hospitalized Mike, never speaking to him again (at least in this film), and accepts a job promotion in his place.

David Essex as probably the least-sympathetic leading man ever. Still, the role made him a star

After who knows how many dead-end jobs and empty sexual conquests, Jim drags himself back home to his mother, who is caring for his invalid grandfather. Terry and his sophisticated university friends want nothing to do with him and his low-class rock & roll fandom (they’re all jazz snobs). He starts dating Terry’s sister Jeanette (Rosalynd Ayres), but almost immediately cheats on her with her best friend (Beth Morris). Jeanette becomes pregnant, and Jim tells everyone he’s getting his act together and going to night school. In reality, he’s hitting the clubs to feed his need to be close to the rock & roll nightlife. He can’t bring himself to marry Jeanette, and eventually runs off again, abandoning his innocent girlfriend, put-upon mother, and newborn child, repeating the cycle of his own father.

The last thing we see is Jim buying a guitar.

Well, no amount of Essex’s charm and good looks can disguise the fact that Jim MacClaine is an absolute dumpster fire. But David Puttman wasn’t wrong…at the time. David Essex became a legitimate star due to That’ll Be The Day, with youthful British audiences at the time so enamored of the freedom of the rock lifestyle and rebelling against the repressions of earlier generations that they were willing to overlook the fact that MacClaine was a callous, selfish shit-stain of a human being, not to mention an unrepetnant serial rapist. Despite being embraced by the shaggy hedonists of the early ‘70s, any discerning modern viewer would see him as a total monster, and him being the protagonist of the movie makes for a difficult watch these days.

There was nothing wrong with Essex’s performance. He acquitted himself in his first starring film role quite well, especially when you consider the character he had to work with. But Ringo was a revelation. Relaxed, earthy (we even get a bare butt shot — imagine what the screaming girls of ‘64 would have thought of that), and easygoing, he imbues the character of Mike with a natural wit and gritty street wisdom. He is certainly amoral to a degree, but compared to Jim, he’s a saint. He’s only in the film for about twenty minutes, but he dominates his scenes in a way we haven’t seen since A Hard Day’s Night. It’s easily the best acting performance of Ringo’s career. Perhaps the secret was letting him improvise.

Once Mike’s story arc is concluded, the film basically becomes a drab, weepy, kitchen-sink melodrama, and my interest in stupid-ass Jim and his stupid-ass “problems” plummeted like a cartoon anvil.

That’ll Be The Day was a huge hit in the U.K., and a moderate success in the U.S. It was successful enough to warrant a sequel the following year. Stardust continued Jim’s story as a rising rock star dealing with immense fame through the 1960s. Ringo declined to reprise his role. “I couldn’t face Beatlemania again,” he explained. The role of Mike Menarry was re-cast with British pop star Adam Faith (despite the name, not one of Larry Parnes’ discoveries.)

Does Jim MacClaine have a redemption arc? I wouldn’t know. Since Ringo isn’t in it, Stardust falls outside the scope of this discussion, and I do not want to spend another second with that asshole Jim MacClaine.

Ringo spent the spring of 1973 finally committing to recording his first true solo album, Ringo. Once that was done, he turned his attention to completing the Nilsson/Count Downe project, otherwise it would be over a million dollars down the drain. After re-titling it Son of Dracula, Ringo reached back out to director Freddie Francis for help finishing the project off. Francis laughed him out of the room, wanting nothing more to do with it.**

Evidence suggests that Ringo himself and a few assistants did the final edit.*** And while no one would give an award for Son of Dracula’s editing, it was perfectly serviceable, proving again that Ringo knew what he was doing in this area. I guess it makes sense for a drummer to intuitively understand film editing, since it’s all about pacing and “beats,” and creating a movie’s rhythm.

At some point in the post-production process, Paul Buckmaster was brought in to provide a score. Buckmaster was one of the most prominent string arrangers in the pop music business, known at the time for his extensive work with Elton John, and also the Rolling Stones (his strings on “Winter” are sublime), and Nilsson himself (“Without You”). Buckmaster’s spooky, dissonant score was one of the high points of a pretty dire project.

At long last, a final cut came together.

SON OF DRACULA

Released: April 19, 1974 (Atlanta, GA.)

Director: Freddie Francis

Producer: Ringo Starr

Screenwriter: Jennifer Jayne (writing as “Jay Fairbank”)

Studio: Apple Films (distributed by Cinemations Industries Inc.)

Cast: Harry Nilsson, Suzanna Leigh, Ringo Starr, Freddie Jones, Dennis Price, Skip Martin, David Bailie, Shakira Baksh, Beth Morris, Dan Meaden

After a brief prologue in 1880, where the original Count Dracula (looking here much like Count Orlock in 1922’s Nosferatu) is dispatched by an unseen hand, we jump ahead to a near-future 1980 London, where Count Downe (Nilsson) — the music-loving offspring of Dracula and a mortal woman, “born in the manner of the human world” — has just passed through the Channel tunnel (in reality not completed until 1994) to stalk London’s nightlife. He meets up with what appears to be his mentor, Merlin the Magician (Ringo), who tells him he is to be crowned “King of the Netherworld.” Downe seems indifferent about this, until he falls in love with Amber (Suzanna Leigh), and decides he is done with the whole vampire thing. Is Amber a vampire herself? The film can’t make up its mind, and devolves into incomprehensible gibberish at this point.

Baron Frankenstein (Freddie Jones) seems to be Downe’s rival for the title of King of the Netherworld (or “Overlord of the Underworld,” the film goes back and forth between combinations of the two titles), and is revealed to be the original Count Dracula’s killer. There are long, pointless scenes of Downe wandering slowly through Merlin’s “Museum of the Occult,” where the exhibits are alive (or at least “undead”), and a few random performance sequences, including the aforementioned setpiece on the Surrey Docks, where Downe on piano is backed by a full rock band. The nine songs in the film are all taken from Nilsson Schmillson and Son of Schmillson, except “Daybreak,” which was composed specifically for the project (and, like most of Nilsson’s stuff from this period, is pretty good). Merlin takes out the Baron by shooting a magic billiard ball at him (I think that’s what happened, I honestly can’t be sure). Dr. Van Helsing (Dennis Price) agrees to use a “Radioactive Transfusion Machine” to turn Downe human, so he can live happily ever after with Amber (who is also Van Helsing’s daughter).

We all know Ringo can be hit-and-miss as an actor, and here is a miss of colossal proportions. Buried under a long gray wig and massive wizard beard, he recites his lines as if he’s reading them for the first time. It doesn’t help that Merlin’s Liverpudlian monotone is the sole source of what little exposition and context there is. And Nilsson is an absolute non-entity. It’s not fair to call him a bad actor, because nothing he does can be remotely described as “acting.” He does nothing more than move from place to place, speak words with no inflection, and fill a physical space. The only times he shows any real screen presence is when he’s performing his music. As you might expect, the musical sequences are the only things in the film remotely worth the time to view.

At the Atlanta premiere, April 1974

Apple Films finally cut a deal with Cinemations Industries Inc. for distribution, and Son of Dracula was officially premiered in Atlanta, Georgia in the spring of 1974. Ringo remembered it as a festive event, with bands playing and 12,000 “screaming kids” in attendance. “But when we left, so did they.” Son of Dracula never got any kind of wide release, but traveled from town to town like an itinerant hobo. Through 1974 it played in random suburbs of Detroit, Phoenix, St. Louis, and Boston. “The movie only played in towns that had one cinema, because if it had two, no matter what was down the road, they’d go there!” said Ringo. It flitted in and out of the L.A. area around Thanksgiving, and by the time it got to Reno and Honolulu in early ‘75 it was showing under the title Young Dracula, to capitalize on Mel Brooks’ recent hit Young Frankenstein. The “Young Dracula” print ads hyped Ringo as the star, and used a late Beatles-era picture of him with fangs painted in. By then, Cinemations Industries, Inc. had filed for bankruptcy.

One last hail-mary attempt to salvage Son of Dracula was made. Ringo hired Graham Chapman and his current writing partners, Douglas Adams (soon to create Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy) and Bernard McKenna, to write a new dialogue track — this time with actual humor and jokes — to be overdubbed onto the existing visuals for a possible re-release. This desperate move came to nothing. (Nilsson showed his personal VHS copy of the Chapman version at a Beatles convention in 1982. This remains its only public screening.) Son of Dracula made the midnight movie rounds and popped up on late night TV from time to time, but no version has ever been released on any home video format. A million dollars went down the drain after all.

Ringo seemingly had the final word: “It’s not the best film ever made, but I’ve seen worse.” Sorry, Ringo, but this is one of the absolute worst pieces of crap I’ve ever laid eyes on. (Notice I said “one of.” Ringo’s Sextette still lies in our future.)

After the Son of Dracula fiasco, Apple Films put out one more release, the Harrison-produced Little Malcolm, based on a play by David Halliwell, starring John Hurt, and seen by no one. By 1975, John, George, and Ringo had tired of Apple, shuttered all the subsidiaries, and moved on. The company went into a long hibernation, its life-support systems monitored by trusted Beatles associate Neil Aspinall. Apple came roaring back to life in the ‘90s as a licensing powerhouse when interest in Beatles-branded merchandise surged.

By the end of 1974, Nilsson’s voice was showing the effects of his lifestyle, and would never be the same. He remained a revered cult figure and a musician’s musician, but went into semi-retirement and became a gun control activist after being profoundly affected by John Lennon’s murder in 1980.

Nilsson’s Mayfair flat seemed a little cursed to say the least. During his L.A. sojourn in 1974, he rented it to Cass Elliot — who died there. In 1978, he rented it to Keith Moon — who died there.

Nilsson sold the flat, and his London years came to a sad close. After years of health problems, he finally succumbed to heart failure in 1994 at the age of 52.

Up next, Ringo plays Pope Pius IX. I’m not kidding.

*Granada was the ITV franchise for northwest England (including Liverpool). The famous early footage of the Beatles performing “Some Other Guy” in the Cavern Club in August 1962 was filmed for Granada’s human interest show Know the North, but was shelved at the time due to low technical quality.

**Francis’ next film was also a “Jay Fairbank”-penned horror flick, Tales That Witness Madness, which made it to theaters a year ahead of Son of Dracula. There would be no further “Fairbank” scripts (Jennifer Jayne turned out not to be much of a writer), and a fed-up Francis began contemplating a return to cinematography — which he did, giving us great work on films like The Elephant Man and Dune, and winning a second Acadamy Award for Glory.

***Wikipedia — and only Wikipedia as far as I could find — lists Garth Craven and Neil Travis as editors on Son of Dracula. Both were respected pros with long careers on much more prestigious projects. SoD is mentioned nowhere in anything else associated with them. Maybe they were the otherwise unnamed “assistants” called in by Ringo for a quick, off-the-books salvage job?

Pingback: Act Naturally: The Films of the Solo Beatles (Part 5) | Holy Bee of Ephesus